It’s a common gripe: Outdated regulations obstruct innovation; government regulators move too slowly or, worse, try to block technological progress. But when conditions are right, regulations can sometimes change quickly, often in a way that promotes innovation. That’s what happened in the case of ridesharing in California.

Companies like Uber and Lyft now have such sophisticated political strategic machinery it’s easy to forget that, only a couple of years ago, ridesharing faced a very real possibility of being shut down. In 2012, regulators in the companies’ home city of San Francisco could have chosen to enforce existing rules, effectively quashing the ridesharing business model. Ridesharing was indeed banned in some places, like Las Vegas, Seoul and France. But many more places have followed San Francisco’s lead in legalizing it.

In 2013, California policymakers created a new set of regulations for ridesharing after a relatively short rule-making process. What explains this friendly response?

We investigated this question last year through a series of interviews for the Transforming Urban Transport project at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. We found three main factors that explained why regulators were so supportive of ridesharing in San Francisco: political support for local industry, a dysfunctional taxi system and regulatory gray areas.

Political support for local industry

Most obviously, Uber, Lyft and Sidecar were headquartered in San Francisco, and regulators beholden to elected officials felt pressure to support local industry. At least one of the companies’ investors was active in local politics.

In 2012, San Francisco’s mayor, Ed Lee, had just been elected on a platform of creating jobs, important to a city still climbing out of the Great Recession. “Sharing economy” startups such as Airbnb were seen as a way to energize the local economy and create a “local” export.

Further, local and state politicians were keen to maintain the reputation of both San Francisco and California as founts of innovation. In particular, local support for the tech industry would bolster San Francisco’s rising position as the new hub of Silicon Valley.

It’s simply not true that government regulators always get in the way.

Political support for industry was important, but not sufficient. Cities don’t allow just any local startup to break the rules in the name of innovation. Other factors were at play.

Dysfunctional taxi system

For decades, getting a cab in San Francisco was a miserable experience. Our interviewees on all sides agreed that the city was a place where “you couldn’t get a cab.” Outside of the downtown area, one could not expect to hail a taxi on the street, while telephone dispatch would regularly take 20 minutes or longer — if the taxi showed up at all.

Jordanna Thigpen, Executive Director of the city’s Taxi Commission from 2008 to 2009, told us, “We did studies that showed taxis never went out to Bayview. These communities didn’t have a voice. Elderly and disabled people… couldn’t get a cab.”

Source: Marlith under Creative Commons

There were too few taxis. Studies conducted in 2001, 2006 and 2013 all reported serious shortages in taxi supply because of permit caps originally designed to benefit taxi drivers. No other major city in the U.S. had such severe shortages.

The city had been trying to reform its taxi system since the late 1990s, with little progress. Part of the problem was that, unlike in other cities where large taxi companies dominated the market, San Francisco’s unusual permit system had created a fragmented industry where medallion owners, taxi companies and drivers all fought for their own interests.

So when Uber and Lyft appeared on the scene, the improvement in mobility was obvious. More so than in other cities, in San Francisco the companies could convincingly argue their services benefited residents ill-served by taxis. They could also more easily rally customers to their cause. Moreover, the city’s politically fragmented taxi industry was uniquely unprepared to defend itself.

Exploiting regulatory gray areas

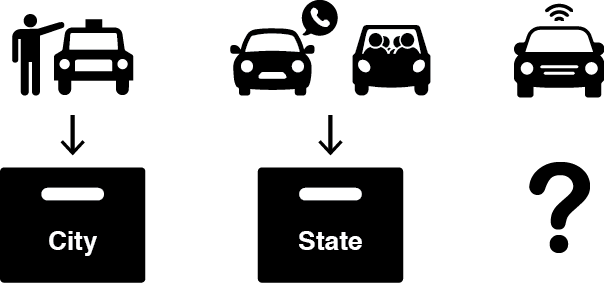

Ridesharing companies and their political advocates exploited a gray area in the regulations and — perhaps more critically — a gray area in jurisdictions. This is important: In California, state law governs black cars and carpooling, while municipal laws govern taxis. Ridesharing fell somewhere in between.

Image credit: Lisa Rayle with icons created by Laurent Canivet, Luis Prado, Gregor Cresnar and Stanislav Levin from Noun Project

According to California law, black cars must be “prearranged,” whereas taxis can be hired on demand. But Uber’s smartphone app sped up the prearrangement process such that it was effectively on demand, blurring the distinction between a black car and a taxi. Uber’s first product, later known as UberBLACK, fell into this gray area.

Lyft and Sidecar, meanwhile, created products that blurred the lines between a black car, a taxi and carpooling. Like a black car or taxi, the traveler could request a ride, but, like carpooling, the ride came from a “friend,” paid for by a “donation.” (Uber later adopted this model as well, with UberX.)

Ridesharing violated regulations for whatever it was considered (black cars, taxis or carpooling). But it didn’t fit neatly into any box. More importantly, because it didn’t fit the existing boxes, it was unclear who should regulate it — the city or the state.

It’s good idea to understand not only what the regulations are, but who is responsible, and the political context surrounding them.

The question of who would regulate was critical because the city offered a very different political context than did the state.

San Francisco in 2012 and 2013 was a battleground between the city’s leftist progressives, who prioritized protecting existing communities and sympathized with local taxi interests, and centrist moderates, who welcomed economic growth and development brought by the city’s booming tech industry. (It’s a debate that continues today.)

Tensions between San Francisco’s progressives and moderates played out as protests against Google’s employee shuttle buses in 2013. (Photo credit: Chris Martin)

Local elected officials historically favored strong labor protections and strict rules for taxicabs — not good news for Uber or Lyft. Although the city’s centrist mayor, Ed Lee, generally supported tech companies, the legislative branch (the Board of Supervisors) was split. Some supervisors liked ridesharing, but others vocally supported taxi interests. That same year, the Board of Supervisors threatened to impose tough regulations against Airbnb, whose operations were clearly within the city’s jurisdiction. If the Board took up the debate over ridesharing, the companies would face an uphill battle.

The State of California, in contrast, offered a much more supportive environment for ridesharing. State-elected officials, while liberal by national standards, were largely pro-business and pro-innovation. The taxi industry was not a player in state politics. The state regulator (the CPUC) was likely to be more lenient too, since regulating for-hire transportation was a minor concern in relation to its far greater responsibilities for overseeing energy, telecommunications and oil and gas transmission.

Both San Francisco and California regulators initially did act to reign in ridesharing. But ridesharing companies had friends in the mayor’s office, and Lee’s advisors concluded the state CPUC offered a friendlier venue than the city’s Board of Supervisors. The local taxi regulator was blocked from cracking down on companies. The city’s strategic inaction effectively pushed the issue to the state, where it found a more receptive audience.

The importance of the right time and place

In the end, the ridesharing model in some form probably would have eventually succeeded, even with only one or two of the above factors. San Francisco had all three: support for local industry, an especially dysfunctional existing system and regulatory gray areas. Other factors helped too, like a population of high-income early adopters who appreciated not having to drive.

The combination of so many favorable conditions helps explain why regulatory change happened when it did, and why it happened so fast. In little more than a year after Uber and Lyft rolled out, the controversial product — hired rides using “regular” drivers — became legalized.

This case shows that it’s simply not true that government regulators always get in the way. The reality is much more context-specific. If you’re a young startup with few PR resources deciding whether to risk confronting the existing rules, it’s good idea to understand not only what the regulations are, but who is responsible, and the political context surrounding them.

The research on which this article is based was conducted as part of the Transforming Urban Transportation project at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, funded by the Volvo Research and Education Foundation. Read one of our previous stories here.