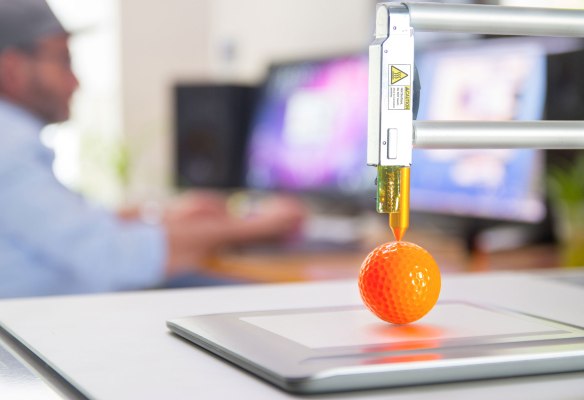

People often ask me about the impact of 3D printing on jobs. Will the technology be a job creator or destroyer? The short answer is, it will take more jobs than it makes — and 3D printing is not alone.

Technology will eventually make work obsolete. Our big problems are going to be figuring out how to survive the transition, then figuring out what to do with all that free time.

The singularity

About 10 years ago, inventor, futurist and now Director of Engineering at Google Ray Kurzweil famously embraced the concept of “the singularity” — that moment in time when machine intelligence surpasses our own. Kurzweil predicted the singularity would occur by 2045, and man and machine would become inseparable.

Given the relationship most people have with their smartphones, you could argue it’s already happening.

For most people, the singularity conjures up one of two themes: Some envision a Terminator-like world, where the machines are in control; others have a more utopian vision, where robots do all the work while people enjoy other, more relaxing pursuits.

Both are distinct possibilities; which scenario manifests itself depends on us.

Transparency

Who doesn’t want more transparency, right? Life would be a whole lot easier if governments, religions, businesses and others would just be honest. Imagine what we’d learn if the doors to the U.S. Government’s National Archives or the Vatican Library were thrown wide open. A lot more than we know today, that’s for sure.

But secrets exist for a reason. They’re an advantage to the states, sects and other organizations that protect them. For individuals, they’re even more valuable. They allow us to project an image that’s different from who we truly are.

In the age of singularity, does any of that really matter?

Computing power continues to grow. Moore’s Law dictates that processing speed doubles every 18 months. But, there’s also an exponential impact.

What are we doing with all that power? It used to take years of man hours to sequence DNA, and the cost was staggering. Look what’s happened over the past 15 years:

[graphiq id=”7lW9Znz6F2B” title=”Cost per Genome Over Time” width=”600″ height=”555″ url=”https://w.graphiq.com/w/7lW9Znz6F2B” link_text=”Cost per Genome Over Time | Graphiq” link=”https://www.graphiq.com/wlp/7lW9Znz6F2B”]

Advancements in quantum technology could push us way past the current pace. But what does any of this have to do with transparency?

Computer technology is advancing to the point where it will soon become very difficult to keep a secret. Not only is more data being collected in more places, but the algorithms needed to find, index and process all that information continue to improve.

That data is being used in all sorts of interesting ways. Not only does it allow police to identify the potential for crime and other high-risk events, it also could help predict when, where and how those crimes will occur.

But at what point does technology go from being predictive to becoming entrapment or, worse, a self-fulfilling prophecy?

Where do we draw the line?

Some of the world’s brightest people, including Bill Gates and Elon Musk, think artificial intelligence has the potential to be very harmful to humanity.

Stephen Hawking definitely falls into the Terminator camp. In a recent letter he wrote,

“it will only be a matter of time” before AI technology reaches a point where it can deploy autonomous weapons capable of “assassinations, destabilizing nations, subduing populations and selectively killing a particular ethnic group.”

This isn’t your average ordinary doomsday prophet, it’s Stephen-Freaking-Hawking!

With better data comes better diagnosis

Whether the intelligence is human or artificial, it all starts with access to data. If the goal was to target a specific group for instance, that group would first need to be identified. Sadly, that would probably be relatively easy with all the data available online; ironically, much of it is self-reported via social media.

Machines will be better at math, science and engineering than we will.

But consider an alternative scenario. Let’s say you’re really sick and go to the emergency room. The hospital uses artificial intelligence to diagnose your symptoms. In real time, machines scan your DNA, review your medical history and analyze your vital signs.

AI can diagnose the problem much faster and more accurately. Plus, doctors work insane hours, seeing an average of 80 patients per week. Machines never get tired.

If your life was at stake, would you want machines to have access to your private, personal information? In either of the scenarios above, it may already be too late.

Privacy matters

The battle between privacy and transparency wages on. Encryption, net neutrality and other related issues are daily news. But if it’s a war, we’re like double agents — and which side we take depends.

The Internet of Things is the next frontier. A growing number of smart devices — from phones to cars, TVs and refrigerators — are being manufactured and sold to consumers. The pitch is convenience.

Consider the Nest thermostat. Consumers buy them so they can more accurately control the temperature in their home — and they can do it remotely via an app. But that thermostat is a sensor, and it’s connected to Internet, sharing its data.

In that instance at least, we’re willing to give up some privacy for the convenience of automation. But is transparency really a benefit?

Imagine if our energy use was totally transparent. While that might have a positive impact on overall consumption, it could also create some really weird scenarios. Imagine playing golf with your buddy and he says, “Saw you had your thermostat set to 65 last night. You know, if you set it at 70 or 72 instead…” which is right about the time you threaten to brain him with your 5 iron.

Automation’s break-even point

“You can kill it with labor, or you can kill it with technology.” It’s a phrase I’ve uttered so many times in my career, I should print it on the back of my business card.

What most people don’t get, though, is that there is always a break-even point — and I mean a specific number — when it makes more sense to kill it with technology.

Years ago I was working with a 2D printing company. They were growing their sales, but were experiencing a common bottleneck: order management. Here’s how it got solved. They had a meeting and asked customer service how many orders they could process each day. The customer service manager said she insisted on reviewing each order that came in the plant. The sales manager asked how many orders she could review each day. She said, “about 30.” The sales manager turned to the CEO and said, “Great, I’ll go tell the salespeople not to take more than 30 orders a day.”

Thirty was the number. Soon after, they automated.

It’s not just a software thing, either. Hardware decisions go the same way. Before digital, the 2D printing process typically involved more than 30 steps and needed 20 different people. It was inefficient.

You can kill it with labor, or you can kill it with technology.

When people began to print on demand, order sizes started to decrease. The decision about whether or not to buy a digital press came down to a number. When the average order value at a print shop decreased to a certain amount, they could no longer afford inefficiency. They had to act.

The amount was $500; when their average order size dipped below that, they automated.

To do it, they needed streamlined processes, better technology and fewer people. In some cases, the combination of digital hardware and software helped reduce the process of printing to four steps that could be completed by just one person.

It’s not just the printing industry. Fast-food workers demand higher wages, and fast-food restaurants started experimenting with self-service kiosks.

YONGE STREET, TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA – 2015/05/27: The technology invading business to save jobs: McDonald’s self-ordering kiosk installed in a building. (Photo by Roberto Machado Noa/LightRocket via Getty Images)

Many would argue $15 per hour is the number. Above that, they’ll automate.

Killing it with technology

In the abstract, everybody gets it. But when the pink slips start flowing, things get personal.

Thousands of jobs were lost as the printing industry migrated from “killing it with labor” to “killing it with technology.” Companies that resisted the transition perished. The industry consolidated and, as a result, today there are a lot fewer print shops.

Those that remained were forced to become more productive.

Fewer shops with fewer employees, operating at a higher level of productivity. The smart ones even began measuring their progress.

Let’s say you’re a $10 million shop with 50 employees. Your average productivity per employee is $200,000. How could you improve? Hire better people, provide better training, improve your business processes and leverage technology wherever possible. As a result, maybe you achieve $300,000 in productivity.

If you were successful, you could grow to $12 million without adding another body! Or, you could satisfy you current book of business with 12 fewer employees.

We’re all being automated

Consider the trucking industry for a moment. Autonomous vehicles could soon have a massive impact. Operating costs over a truck’s lifetime (about 600,000 miles) would drop by about half using self-driving trucks versus rigs driven by people.

Even if people are still in the cab, the impact of technology could be huge. Driver-safety aids alone could save billions in accidents, fines and other costs.

Again, machines don’t get tired.

The pace is accelerating

It’s not just the pace of innovation, but also the pace of adoption. The iPhone was introduced less than 10 years ago. Now nearly 2 billion people worldwide have smartphones. It took the PC 25 years to become that pervasive.

Imagine if you got in your car tomorrow and a notice was flashing on your screen that said, “new features have been installed.” Overnight, via a software download, the manufacturer updated your car so that it could drive more-or-less autonomously. What would you think?

Well, it actually happened. Last October, Tesla broadcast a software update that gave owners the ability to drive on “Autopilot.” Soon after, a Tesla was driven cross-country in fewer than 60 hours — and was driven autonomously 96 percent of the time. In some cases, as much as 40 minutes went by without a driver touching the steering wheel.

Source: Tesla

Designing for the future

Should I expect my 2015 Ford Fusion to receive such an update? No, it’s too mechanical. Even though the computer in my car processes more lines of code than all the computers in the world combined just 50 years ago, it doesn’t have the sensors and control necessary to enable semi, much less fully, autonomous driving.

But Tesla laid down the gauntlet, and now the auto industry is spending billions to catch up.

Should machines break the law?

It’s an important question to address as machines become more autonomous; instinctively, we’d say no, they shouldn’t break the law. But how about this example. You’re riding in an autonomous car and it’s getting on the freeway. The manually driven vehicles are all driving 75 MPH in a 55 zone. Does the autonomous car speed up to merge, and in the process break the law, or does it attempt to merge at the speed limit. If the latter, I imagine the potential for road rage goes up significantly.

I’ve talked to more than a few people who suggest that autonomous vehicles would have their own lanes, or be geo-fenced somehow. While that may work in the long term, there is a massive transition between then and now. The average car is on the road for 11 years. It will be at least 20 years before autonomous cars outnumber human-driven vehicles.

Surviving the transition

Will man and machine battle it out, or will we reach the utopian vision of man unshackled from work? It comes down to how we handle the transition.

Take the minimum wage for example. Yes, $15 an hour might be the catalyst, but even if it remains at the current, federally mandated $7.25 an hour, some, if not all of those jobs will eventually be automated.

A while back, the CEO of Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr., Andy Puzder, made the case for why his company was experimenting with self-service kiosks. He said, “You’re going to see automation not just in airports and grocery stores, but in restaurants.” He added that machines are, “always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there’s never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex, or race discrimination case.”

I’d also note that machines don’t eat fast food. Who does, right? Well, ironically, most of the 20,000-plus Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr.’s employees, for starters.

Beyond them, surprisingly, it’s not as much the poor as it is the lower-middle and middle class. At incomes above $60,000, fast-food patronage begins to taper off. But, according to a not-so-recent Time article, it’s also “well established that low-income neighborhoods tend to be “food deserts” — where fresh, whole foods are scarce and where the bulk of available food is the high-fat, high-sugar stock of convenience stores.”

By eliminating lower-income jobs, the industries that are most ripe for automation may also be eliminating their best customers, and that’s not sustainable.

The 7 Ps

After hundreds or thousands of years of building, leaders of some civilizations started to see a need for urban planning. The Romans were master planners. Here in the United States, one of the earliest examples was the Grand Model for the Province of Carolina.

Originally drafted by John Locke, it greatly influenced the development of Charleston, South Carolina, among other places. His urban plan provided detailed standards for block size, lot size, street width, waterfront setbacks and other standards. Arguably, it set the tone for modern planning and zoning ordinances here in the U.S.

Planning for singularity

Even back then, Mr. Locke knew that piss-poor planning promotes piss-poor performance. It seems more obvious every day that man and machine are quickly assimilating. The transparency that’s inherent in technology will eventually destroy privacy. Automation will eventually eliminate the need for human labor. There’s a short window of time between then and now. We need a master plan for how we’ll manage the disruption that goes along with it.

Technology will eventually make work obsolete.

People need to understand what’s coming and must be prepared. They’ll need new skills. We’ll need new financial models. Some have suggested a Universal Basic Income. They believe the increases in productivity that come with automation will generate the wealth necessary to pay for it. They also contend that with that kind of economic security, we’ll all become artists, poets and playwrights.

Maybe so, but right now we’re training our kids for the opposite. We’re emphasizing science, technology, engineering and mathematics. While those skills might be necessary to get us to the point of singularity, they’re also ripe for obsolescence once we’re there. Machines will be better at math, science and engineering than we will.

If all of this actually happens in 2045 as Mr. Kurzweil predicted, a child born today will be 30 years old and will have the potential to live forever. Maybe the big question then is, what will they do with all that time?