In the first part of this series, we learned about designing products that use good triggers and motivators to get users like Joe to engage in healthy behaviors. Now, how can we ensure that these new behaviors become long-term habits?

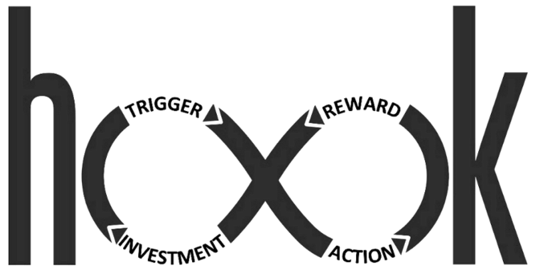

In this second part, we return to Nir Eyal’s Hooked model to look at reinforcing Joe’s behavior through rewards and an investment in your product.

Rewards

Rewards serve as a way to positively reinforce users for the actions they take.

Interestingly, brain imaging studies show that it’s not the sensation of the reward that excites us. Rather, it’s the anticipation of receiving the reward that activates the brain’s pleasure centers.

When a reward is given each time after a good behavior, anticipation fades away, making the behavior seem dull and routine. However, when the reward is given in an unpredictable manner, we start repeating behaviors for the thrill of the chase. It’s the reason people play slot machines; they don’t win money each time — the thrill of hitting the jackpot is way more exciting than the money itself.

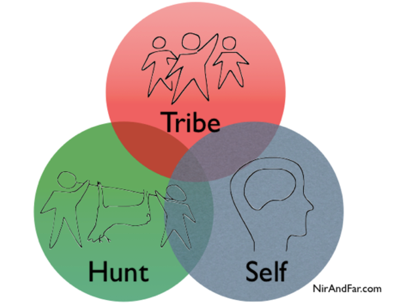

So, variable rewards can also be very powerful in repeating healthy behaviors. In Nir’s Hooked model, there are three types of variable rewards: rewards of the tribe, hunt and self.

Rewards of the tribe

We are social creatures. We crave belonging, connection and acceptance from other people. As such, rewards of the tribe are very powerful in encouraging repeated behaviors. Let’s look at some of these rewards.

Rewards of competition

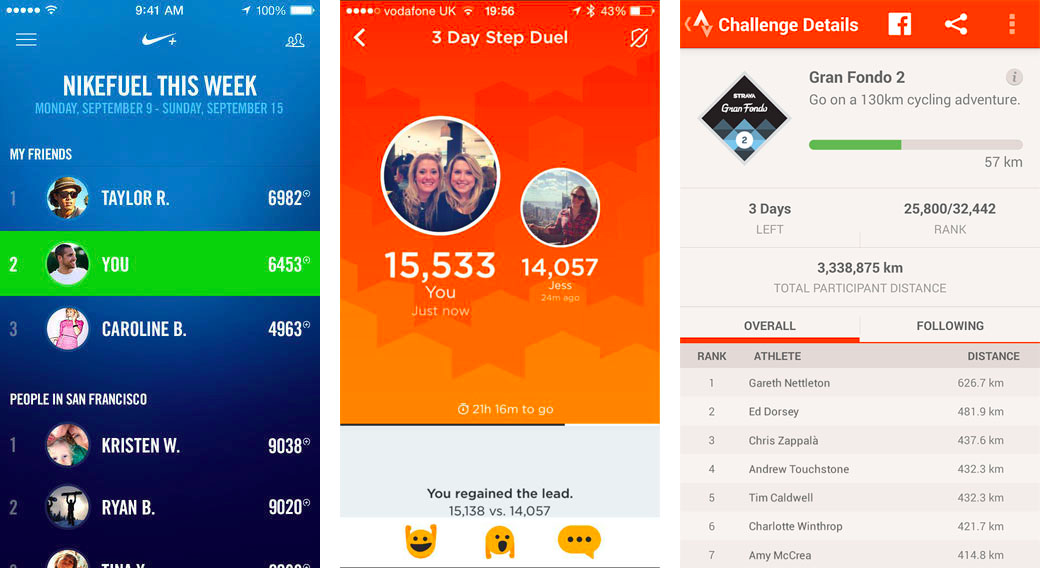

Competition is a powerful social motivator. It establishes your status within the community, and gives users a good sense of self-esteem.

Health apps use many gamification concepts such as leaderboards and user challenges to achieve this. The reward of winning is highly variable, because your rank is not only dependent on your performance, but also how others have performed.

Nike+ Leaderboard (left), Jawbone’s Duels (middle) and Strava’s League Challenge (right)

For the user, this causes a strong craving to reach the top. In fact, studies about gaming found that fear of losing in a competition is an extremely powerful motivator for users to get better next time!

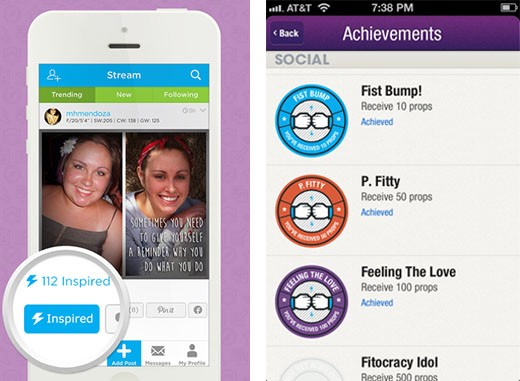

Rewards of cooperation

Rewards from cooperation can be a sense of belonging, feeling a part of a community, feeling wanted and loved.

Apps such as Fitocracy and Weilos use social feeds to make it easy for users to join groups and encourage one another. Upon completing their goals, users get rewarded with props and encouragement from fellow members.

Weilos (left) uses “Inspired” and Fitocracy (right) uses “Props”

The praise the user receives each time is variable. This creates a sense of craving, to keep on sharing and working out on the platform to receive approval from peers.

Rewards of the tribe are extremely powerful for users, and are also a great way to foster an active and thriving community around your product.

Rewards of the hunt

We as a species are also excited by the thrill of the hunt. What once used to be a hunt for food, animals and shelter has now translated into a hunt for things like money, fancy objects and deals.

Gamification concepts of rewarding users with badges and trophies is common in many health app these days.

From left to right: Strava, Nike+, Fitocracy, Fitbit

These rewards are given for completing different actions. They are doled out in a variable frequency, making it thrilling for users to achieve them.

Rewards of the self

These are rewards that satisfy our intrinsic need for personal excellence and a sense of competence.

A lot of health apps accomplish this through gamification techniques, such as levelling up and progress bars.

Credit: Superbetter

One of my favorite examples is Joyable, an app used to help people reduce social anxiety. Users attempt a series of tasks progressively from low to high anxiety, giving them a progressive sense of control of their anxiety.

A note about gamification

With the increasing popularity of gamification, it might be tempting for us as product makers to want to use them all in our products.

But slapping gamification concepts onto a product, without consideration about who the users are, will only lead to poor product design.

We need to ask ourselves, will this reward actually motivate my user?

For example, research in gamification shows that only the top 5 percent of performers enjoy the leaderboard experience. Poorer performers are actually terrified by leaderboards!

If you’re designing a mass market wearable, pitting the fitness-freak athlete with the out-of-shape middle-aged dad will lead to an unsatisfying experience.

Understanding your users’ intrinsic motivation (which we discussed in Part 1) is essential in designing a good rewards system.

Investment

When users take an action and we reward them for it, they end up making a small commitment of time/effort in using your product.

As product makers, we can leverage this small investment to encourage better behavior in the future. We are strongly driven to be consistent with our own past behaviors. Robert Cialdini, describing his principle of Consistency and Commitment, says that, “Once we have made a choice or taken a stand, we will encounter personal and interpersonal pressures to behave consistently with that commitment.”

Health apps such as Jawbone make an excellent use of our deep need to be consistent with ourselves.

Credit: Jawbone

Jawbone asks users to make a small commitment in the morning to get to sleep by a certain time at night. And at night, Jawbone makes the big ask of reminding you to go to sleep at the time you committed to. And by simply clicking on the “I’M IN” button, 72 percent of their users were more likely to go to sleep on time!

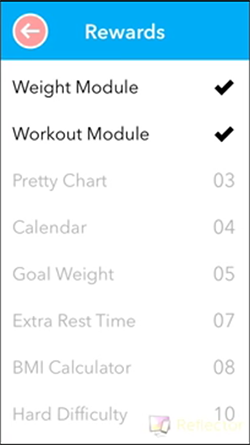

Users also irrationally value their own efforts, which Dan Ariely calls the IKEA Effect. Users tend to value way more a product they’ve spent effort and time on than a product in which they put no labor into. For example, the first time you open Carrot Fit, it only has a basic weight tracking function. The small action of regularly taking your weight earns you points and earns you new functionalities, such as workouts and new difficulty levels. The more effort you put into unlocking the app, the more you end up valuing the app as a result.

By repeating tiny actions, we start valuing highly the results of those actions. And when this happens repeatedly, users start to change their attitude toward the new behavior, setting them on a path toward habit change.

Health apps encourage these tiny actions, by getting users to invest their data, time, content or reputation.

Investing data

Lots of health apps encourage users to key in their weight or their fitness profile, or to import data from other apps. For example, apps such as Sleep Cycle and Pillow track your sleep data. Each day you track your sleep, the new data is used to recalculate your sleep patterns. This makes it much harder for users to leave the apps.

Sleep Cycle (left) and Pillow (right)

Investing content

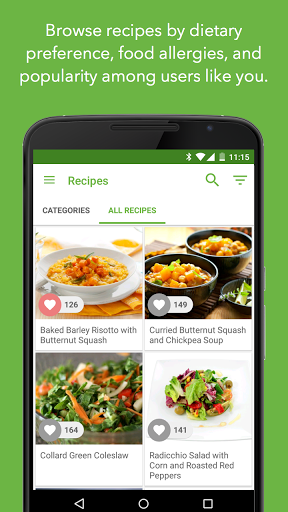

Health apps also get users to invest a little bit of content, making it easier for them to repeatedly use the product. For example, Zipongo, a healthy recipe recommendation app, asks you to enter your food preferences and allergies during the onboarding process itself. So the first time you see recommendations, the content is highly curated for your needs.

Zipongo’s curated recipes

As you “favorite” more recipes, your recipe list gets more and more curated based on users who like similar recipes. By asking users to invest just a tiny bit of information about themselves in the onboarding process, Zipongo ensures that, as time goes on, each action becomes an investment into more curated content. This makes it easier for users to repeatedly use Zipongo for their cooking needs.

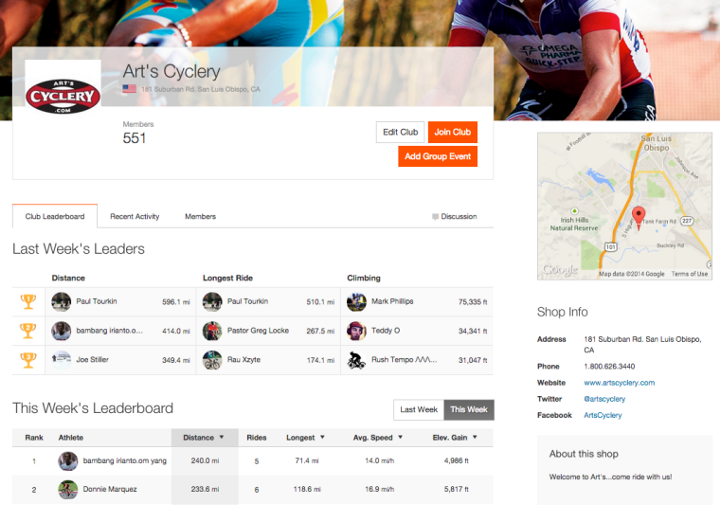

Investing reputation

Apps that focus a lot on social workouts, such as Strava, reward their users with trophies and ranks as a sign of their accomplishments. When users start to work out, they build up a list of trophies and followers. Over time, this becomes a big investment in the product as the user now has a reputation to maintain on the platform.

Investing time

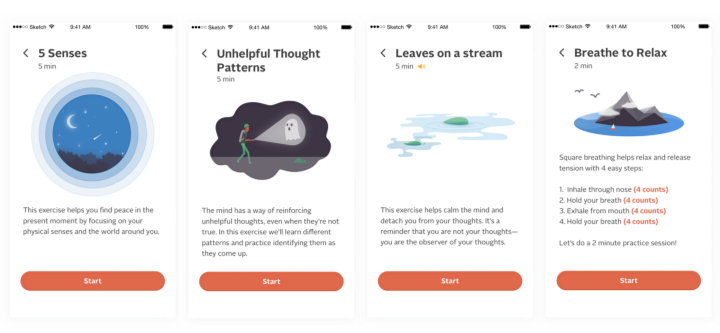

By asking users to invest even just a few minutes of their time and effort, we can get them to keep repeating certain behaviors. Ginger.io is a product that helps users who struggle with depression. It uses short (two-five minutes) exercises to engage users in mindful thinking and behaving.

Credit: Xiayouji.com

Once the user completes an exercise, these are taken into account by the app to tailor future interventions based on the current exercise the user undertook.

Setting up users for next steps

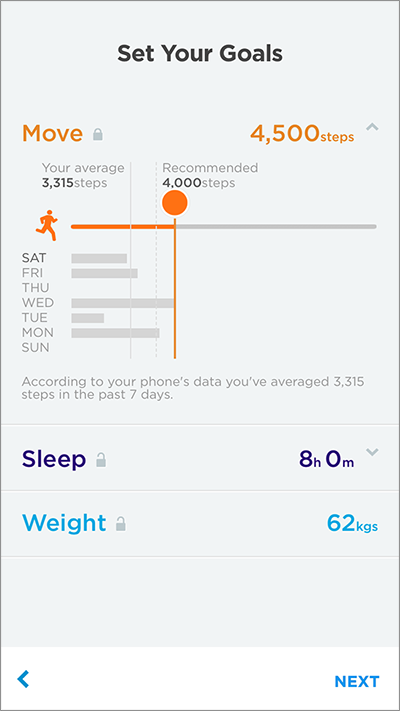

During the investment phase, it is also important to set up future triggers to start the next habit-forming loop. For example, when I first sign up for Jawbone, Step 1 of my onboarding asks me to set my movement, sleep and weight goals. Sure, it’s an easy enough task, and I do it.

Jawbone’s onboarding process

Jawbone then uses this little information I invested to regularly send me new triggers to go to sleep on time and move more. It is important that during the investment phase we are able to get investment that can help trigger users to take action the next time. By doing this, we can increase the chances of a user cycling through the habit-forming Hooked model multiple times.

Tying it all together

Nir’s Hooked model is a great way to look at how we design products that help our users with long-term health behavior and habit changes.

It’s important to encourage good behaviors by giving our users timely triggers, that have a clear call to action. We also need to give users the motivation they need to want to perform that action. By making the action as easy as possible, we also increase the likelihood the user will do it.

A surprising and engaging reward at this time helps users form positive associations through repeated use. Through this process, users invest more in your product, making it more likely that they will cycle through the habit-forming loop. And voila! We’re on our way to forging long-term habits.

The examples I shared are all interesting ways in which companies out there are tackling a difficult problem of habit change. However, these examples aren’t meant to be a one-size-fits-all solution. As product makers, we need to understand our users’ deep pain and what truly motivates them. Everything that we design must flow from that core.

Once we understand our users’ intrinsic needs, the Hooked model can serve as a great framework to design for long-term healthy habit formation.