The more highly technical the basis of a story, the more likely it is that some key detail will get jacked up by a journalist trying to translate it for the public. Call it Panzer’s Law.

It’s only natural, especially when it comes to stories about security and privacy, such as Apple vs. the FBI. There are a myriad of complex technical mechanics at play, fiercely difficult Gordian Knots of encryption and hardware solutions to unravel and a number of previous interactions between Apple and the government that have set one precedent or another.

But no matter how hard it is, it’s important to get this stuff right. The press has the ability not only to act as a translator but also as an obfuscator. If they get it and they’re able to deliver that information clearly and with proper perspective, the conversation is elevated, the public is informed and sometimes it even alters the course of policy-making for the better.

When it comes to the court order from the FBI to Apple, compelling it to help it crack a passcode, there is one important distinction that I’ve been seeing conflated.

Specifically, I keep seeing reports that Apple has unlocked “70 iPhones” for the government. And those reports argue that Apple is now refusing to do for the FBI what it has done many times before. This meme is completely inaccurate at best, and dangerous at worst.

There are two cases involving data requests by the government which are happening at the moment. There is a case in New York — in which Apple is trying really hard not to hand over customer information even though it has the tools to do so — and there is the case in California, where it is fighting an order from the FBI to intentionally weaken the security of a device to allow its passcode to be cracked by brute force. These are separate cases with separate things at stake.

The New York case involves an iPhone running iOS 7. On devices running iOS 7 and previous, Apple actually has the capability to extract data, including (at various stages in its encryption march) contacts, photos, calls and iMessages without unlocking the phones. That last bit is key, because in the previous cases where Apple has complied with legitimate government requests for information, this is the method it has used.

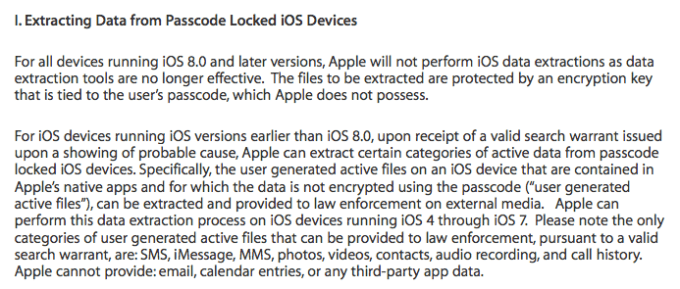

It has not unlocked these iPhones — it has extracted data that was accessible while they were still locked. The process for doing this is laid out in its white paper for law enforcement. Here’s the language:

It’s worth noting that the government has some tools to unlock phones without Apple’s help, but those are hit and miss, and have nothing to do with Apple. It’s worth noting that in its statements to the court in the New York case, the government never says Apple unlocks devices, but rather that it bypasses the lock to extract the information.

The California case, in contrast, involves a device running iOS 9. The data that was previously accessible while a phone was locked ceased to be so as of the release of iOS 8, when Apple started securing it with encryption tied to the passcode, rather than the hardware ID of the device. FaceTime, for instance, has been encrypted since 2010, and iMessages since 2011.

So Apple is unable to extract any data including iMessages from the device because all of that data is encrypted. This is the only reason that the FBI now wants Apple to weaken its security so that it can brute-force the passcode. Because the data cannot be read unless the passcode is entered properly.

If, however, you assume that these stories are correct and that Apple has complied with requests to unlock iPhone passcodes before and is just refusing to do so now, it could appear that a precedent has already been set. That is not the case at all, and in fact that is why Apple is fighting the order so hard — to avoid such a precedent being set.

The New York case has another wrinkle, which is a separate issue. Apple can theoretically comply with the data extraction request there, but is refusing to do so on two bases: extracting data from devices diverts manpower and resources, and that the government is trying to use a wide application of the All Writs Act of 1789.

At the behest of Judge Orenstein, the federal magistrate in the NY case, Apple filed a response in which it questioned the new application of the AWA. Apple also argues that since its reputation is based on security and privacy, complying with the court’s demands based on an expanded application of a 200-year-old law could put it at risk of tarnishing that reputation. Apple is still waiting for a final order on whether to comply from the judge there. The All Writs Act is also being used in the case in California.

Still, even if Apple were to comply in New York, it would not be unlocking the device, merely extracting data off of it with standard methodology for pre-iOS 8 devices. If the FBI succeeds in ordering Apple to comply in California, it would have to build a new software version of iOS that allowed electronic brute-force password cracking. This is an important distinction to make when talking about such an important precedent-setting case.

Article updated to clarify what data Apple can extract.