There have been plenty of premature obituaries for privacy falling from the lips of tech company CEOs in recent years. Yet the idea that people have a sub-set of personal information they wish to keep outside the public sphere persists — despite all the incentives and encouragements for the proverbial user to be as naked as can be when it comes to sticking their data online.

Even the kingpin privacy slayer himself, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, kept the birth of his daughter Max quiet for several days last November — before publishing a 2,000+ word open letter on December 1 to mark the moment publicly. Back in 2013, he also famously bought multiple properties around his own Palo Alto home, affording himself and his family the luxury of a large, private domestic space with no prying neighbors peering over the fence. Privacy dead? Hardly.

The latest confirmation that privacy remains stubbornly lodged in the human psyche comes via a new study, published today by the Pew Research Center, which probes Americans’ attitudes to privacy across a range of different theoretical scenarios — where some advantageous trade-off is suggested in exchange for handing over personal data.

The Internet adage that ‘if it’s free you’re the product’ applies by degrees here. Pew’s researchers sketched out a range different scenarios to survey participants, to test their risk-benefit calculations and attitudes around sharing, and — unsurprisingly — a spectrum of responses was the result.

“A phrase that summarizes their attitudes is, ‘It depends’,” writes report author Lee Rainie, director of Internet, Science, and Technology research at Pew Research Center. “Most are likely to consider options on a case-by-case basis, rather than apply hard-and-fast privacy rules.”

The key takeaway here is that privacy is a deeply personal issue. One person’s ‘happy to share’ might be another’s personal TMI red line. So while Zuck is clearly more than comfortable telling the world what his new year challenge is every January, via a public Facebook post, he’s evidently less happy about letting anyone see what’s going on in his living room.

Point is: You can’t divorce privacy from the individual. People are different — and so there’s no single answer to how much privacy people are happy to trade away to use a particular product/service. Frankly, if Pew had been able to synthesis some “hard-and-fast privacy rules” it would have been far more surprising.

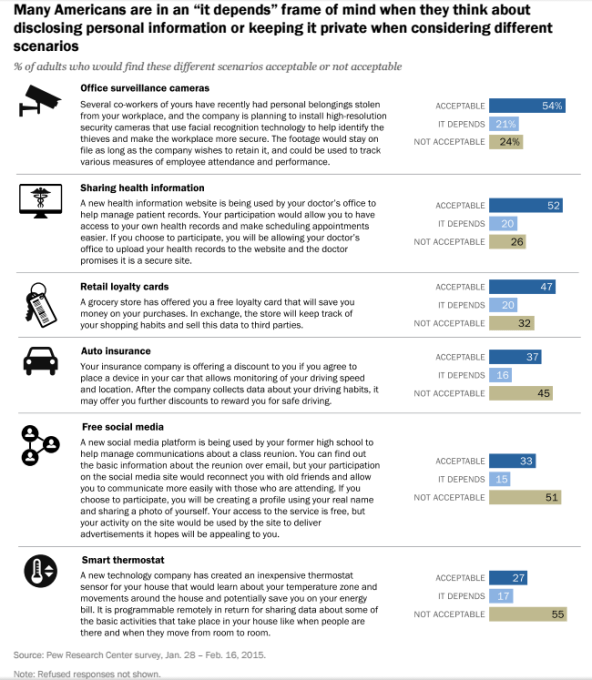

The six ‘privacy probing’ scenarios Pew detailed to research participants were: an employer installing surveillance cameras with facial recognition technology after a spate of workplace thefts, with the footage set to be retained indefinitely and potentially used to track employee attendance and other performance measures; a doctor’s office using a health information website to manage patient records which will make it easier to schedule appointments if you agree to upload your health data; a grocery store offering loyalty discounts in exchange for tracking purchases and selling the data to third parties; an auto insurance company offering discounts in exchange for monitoring driving speed and location; full access to a school reunion social media website in exchange for being profiled for on-site ad serving purposes; and a connected thermostat that analyses your domestic energy usage and could potentially save you money but which shares data on domestic activity with the company that made the gizmo.

While the research organization made sure not to explicitly reference any specific companies in these scenarios, you could easily transpose a few tech giants onto its examples — whether it’s ad-profiling social network Facebook or Google-owned learning thermostat maker Nest, to name two obvious ones.

Participants in the study were asked whether the ‘bargain’ they were being offered in return for sharing their information was acceptable, not acceptable or whether “it depends” on the context of the choice. They were then asked to describe in their own words what factors contributed to making their selection.

What did Pew find? As noted above, a lot of variation, with generally no consistent demographic patterns emerging in responses — whether based on age, gender, income level or other criteria. But interestingly if you rank the six scenarios by how acceptable or not they are, the least acceptable turns out to the last one — involving the Nest-style smart thermostat. Just 27 per cent of participants said they would find this scenario acceptable vs 55 per cent saying they would not. A further 17 per cent said it would depend on the circumstances.

Given Zuckerberg’s own fiercely protective display of privacy when it comes to his own home, this is really not so very surprising. If you want to talk about privacy having a focal point, for the majority of people that point is going to be their home — i.e. their personal, private space. So ‘smart home’ technologies like Nest, which entail the harvesting of in-home activity by a commercial entity, which may then make use of that data in various unknown ways, pose an obvious threat to the sense of peace people derive from having a place where they get to shut the world out.

(Although, in Nest’s specific case, the company stresses it does not share any user data with its parent, Google/Alphabet, and says it only gathers data required to operate the service. You can read its privacy policy here — which does include a provision that it may share “non-personal information” (e.g. aggregated or anonymized customer data) publicly and with partners. It adds: “We take steps to keep this non-personal information from being associated with you and we require our partners to do the same.” As with many such policies, the user’s data privacy rights potentially terminate if the company is sold, with Nest noting: “Upon the sale or transfer of the company and/or all or part of its assets, your personal information may be among the items sold or transferred.We will request a purchaser to treat our data under the privacy statement in place at the time of its collection.”)

And while you might think the notion of an employer deploying face-detecting surveillance cameras that can keep tabs on staff attendance, Big Brother style, might seem highly objectionable, Pew’s researchers in fact found a majority (54 per cent) of respondents were accepting of this scenario — perhaps because being in a workplace already entails having signed a contract agreeing to abide by a third party’s rules. So, in other words: Their house, their rules.

But when it comes to a person’s own home? My house, my rules… For example Pew flags up one survey respondent’s explanation for rejecting the trade-off of potential energy savings in exchange for having their domestic habits tracked as an emphatic declaration that: “There will be no ‘SMART’ anythings in this household. I have enough personal data being stolen by the government and sold [by companies] to spammers now.”

So it looks like smart home startups really need to be putting privacy front and center of their proposition if they want to appeal to the widest possible user-base.

Pew’s researchers also recorded regular expressions of anger “about the barrage of unsolicited emails, phone calls, customized ads or other contacts that inevitably arises when they elect to share some information about themselves” — with, for instance, study participants complaining about the lack of relevant ads foisted into their eye-line, and wishing for more control over the marketing content they are being exposed to.

Another concern flagged up by the research is the lack of transparency about what companies are doing with harvested data. On this point, European politicians finally agreed new data protection rules at the back end of last year which will tighten the region’s rules around data processing consent — with a requirement that companies doing business in the European Union obtain unambiguous consent from consumers for use of their data. And gain consent again if they wish to use the data for a different purpose than originally state. Some Americans may wish the U.S. had similar rules incoming…

On the flip side, the Pew report also flags up the obvious point: that people do like a free service. Although with just 33 per cent of survey respondents identifying the social media trade-off scenario as acceptable to them (vs 51 per cent saying it’s not) you’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise. However with that particular scenario Pew notes there was a considerable difference in responses based on age — with some 40 per cent of those under age 50 saying the deal is acceptable vs just a quarter (24 per cent) of those aged 50 or above being ok with the trade-off.

Pew also suggests “a general dislike of social media and the information that people share on those platforms” might be coloring respondents’ views of the ‘bargain’ being presented here — and thus skewing responses to the negative for that particular scenario.

That then begs the question what is the cause of this “general dislike of social media”? And might it not, at least in part, be associated with the technology’s privacy-eroding habits? Pew’s report details some comments it gathered from participants who were not willing to accept this trade-off — including plenty of disgruntled views about the volume of marketing content they are encountering on such sites these days.

e.g.

- “I do not use social media now because of this. [It is] marketing I do not like, and [I] do not participate anywhere this is used.”

- “Although I understand this scenario is already standard practice, it uses information collected about me in a manner not for my benefit, without my consent. It would affect how I use the reunion site or whether I even join the site at all.”

- “Do not want to view excessive ads and do not want to create more profiles.”

- “Advertised as ‘free,’ but it isn’t. I pay, but with my attention span rather than a monetary fee. Too costly, and based on a lie.”

So it may be a case of some ‘Facebook fatigue’ creeping in here.

Other comments suggest the entire social media category is a victim of Facebook’s category dominating success — with social media in general inextricably linked to Facebook, making respondents see little point in using another similar website. (For example, one participant is recorded saying: “I have enough social media sites to manage. I’d rather they use Facebook. The privacy settings are similar to what’s described and those are fine by me. But I don’t want to start using another site.”)

Facebook’s success and ubiquity in the social media space might therefore be said to have ‘poisoned the well’ for others trying to encourage similar public social sharing — unless they are offering something distinctly different. The more bounded form of social sharing that goes on on mobile messaging apps is one example of a successful alternative social sharing model (so successful that Facebook shelled out $19 billion to buy the dominant player, WhatsApp, back in 2014).

Pew also asked its participants for their views on the future of privacy, and found that most of the focus group participants were downbeat on this — with many believing the trend towards surveillance and data capture is inexorable. Many also said they believe younger Americans are not sensitive about personal privacy. (Although the success of youth-friendly social messaging app Snapchat may suggest otherwise…)

The Pew study is based on a survey of 461 U.S. adults and nine online focus groups with 80 participants, with research conducted January 27 and February 16 last year.