Walgreens, Theranos’ flagship partner, has announced it’s suspending their rollout of new labs pending an investigation of their technology and grocery giant Safeway announced that it’s canceling a roll out of Theranos clinics, a deal worth an estimated $350M.

I’m not an investor in Theranos, have never met Elizabeth Holmes, but I have co-founded two companies in regulated industries that required dealing with the FDA, EPA and other government agencies.

I feel for Ms. Holmes and believe the press accounts unfairly paint her company in a negative light. Innovation that involves sensitive medical technologies is challenging and provokes strong emotional reactions, but the reality is that the strongest criticisms of Theranos have more to do with business structure than their blood tests.

Theranos’ biggest “mistake” was running two businesses at once.

Rule #1 of startups is focus. Theranos is breaking this rule by running a commercial blood testing lab, similar to Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp, and a ground-breaking R&D company at the same time.

Getting to market quickly with off-the-shelf technology generates revenue and buzz. It also creates confusion—Do you focus on increasing revenue or spend on R&D milestones like clinical trials? And which story do you lead with? This internal confusion often bleeds through to the public.

Theranos is running two fundamentally different businesses. It’s one thing for an established company like Google to have a core business like Search and simultaneously run a self-driving car program. It’s harder for startups, even well-funded ones to do the same.

Compare Theranos to Moderna, another biotech Unicorn that is laser focused on trying to create a new class of RNA-based therapies. This Boston based company has nearly $700M in funding, and I’m sure they could launch a revenue producing product line, but that’s not their goal. As a result their profile may be lower in the press, but they’re not subject to any scathing reports.

That said, I have some sense of how I think Ms. Holmes is seeking to develop the technology. Like my experience at Brontes and Sample6, I suspect Theranos is building out a model workflow that combines the myriad pieces that it takes to run a blood lab. As innovations come online, you swap out the off-the-shelf traditional technologies with the proprietary breakthrough ones. This allows for a more rapid development of really hard, unpredictable science.

The Proper Way To Evaluate Theranos

Let’s take a step back and review what Theranos actually offers to customers.

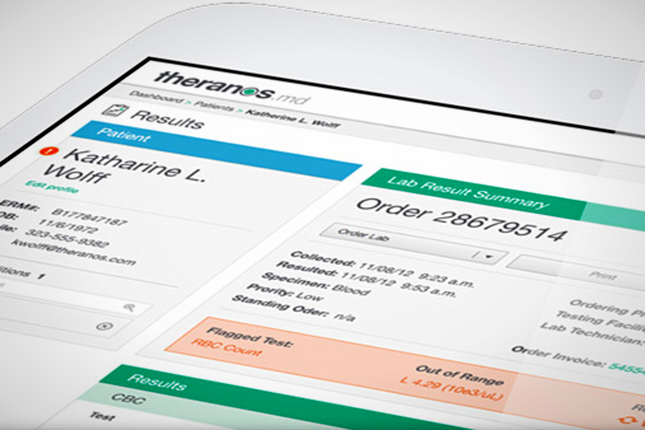

Theranos makes it more convenient to get blood test results by co-locating in neighborhood pharmacies. They also reduce the price of testing dramatically and present the results in a prettier, easier to read format.

Theranos uses traditional lab equipment to provide most of their results. Their eventual goal is to use proprietary “nanotainers” that will allow a variety of results to be produced from a few drops of blood.

That will be awesome, but in the meantime does it matter if your Bilirubin levels are monitored with a breakthrough technology or an industry standard as long as the results are accurate? Especially if they are easier to access, afford, and understand?

Theranos’ largest competitors, Quest Laboratories and LabCorp have combined revenues of over $13B per year. If all Theranos ever did was make that industry more convenient, faster, and prettier using standard tools, isn’t that impressive enough on its own?

Asked another way, how is offering accurate, more convenient tests, at a lower cost, using industry-leading technology—while simultaneously spending tens of millions on R&D that could further reduce the cost, complexity, and pain of blood testing—a bad thing? That’s a vision I’d invest in if given the chance (at the right valuation of course!).

Let’s Translate This into Tech Terms

This becomes even more clear if you compare the Theranos model to some products we’re all more familiar with.

Uber does to the taxi industry what Theranos does to diagnostics—it makes it more convenient and less expensive while providing a much nicer user experience.

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick has also stated he’d one day like to replace many human drivers with autonomous vehicles. Is Uber truly not worthy of all its hype because they haven’t yet cracked the code on self-driving cars? Should Uber also be criticized because they didn’t invent the smartphone? Or Black Camrys?

Theranos has been accused of a bait and switch because they use a competitor’s lab equipment to run most of their tests. Is it a moral failing that Netflix is powered by Amazon Web Services? Netflix has figured out how to add value on the back of a direct competitor’s infrastructure. Does this invalidate Netflix’s business model?

Of course not. We love Netflix because Orange is the New Black is awesome and their user-experience is amazing. This is essentially what’s happening at Theranos at the moment—boring tech is being repackaged and brought to consumers for a small fee.

Reviewing The Technical Case Against Theranos

Let’s “fact check” the technical and medical accusations. The 2,689 word WSJ feature builds two significant cases against Theranos:

First, their “breakthrough” blood testing technology is only used on one of the 150+ tests that they offer. Second, their breakthrough technology gives patients misleading and potentially dangerous results.

Case 1: Theranos supported a misleading story around their tech. True, but startups by definition should evangelize a future vision.

That only one of the tests Theranos offers utilizes their proprietary “nanotainer” is disappointing. The New York Times’ Farhad Manjoo compared the revelation to discovering that Teslas actually run on Gasoline. This is true, but so what? This a clear case of hype outpacing reality. Certainly if Theranos was a public company, they would need to be more careful with guidance, but they’re not.

It’s also important to ask who has been hurt by Theranos’ story?

Customers? Early adopters who read press accounts might have been disheartened to find the vast majority of Theranos’ tests require blood to be drawn the old-fashioned way from a vein. And the company has since changed verbiage on its website in response to the criticism. However, patients always have the opportunity to seek care elsewhere.

Investors? Theranos’ investors could plausibly be upset that the tech they backed isn’t the primary driver or focus of the business, but I suspect they were fully aware of the reality of the current business and are betting on the future vision of the company.

The Media? The most aggrieved party is the press. No doubt many of the reporters who wrote glowing profiles of Holmes surely feel embarrassed for uncritically sharing the company’s claims, but as Google Ventures partner Bill Maris noted, he never met a reporter who actually got a test to verify the startup’s claims.

Case 2: Theranos is operating without sufficient oversight.

The insinuation that Theranos was using an untested technology to give patients life and death medical results, is much more serious. I haven’t seen much evidence to back it up.

They’ve satisfied the (tough) regulations: Theranos has had their proprietary “nanotainer” technology cleared by the FDA for use in the diagnosis of Herpes Simplex. Here is the 510k that Theranos submitted to the FDA that documents “substantially similar” performance compared to a competitive system when tested on 818 patients across 69 devices. There are 22 tables worth of data backing their claims. So Theranos’ core technology works—just not as widely as anyone would like. I’ve filed a 510K—they’re a lot of work, get quite a bit of scrutiny, and aren’t cleared by the FDA lightly.

They Use Industry Standard Tools: The remainder of Theranos tests are reportedly conducted on industry leading machines made by companies like Siemens, a global conglomerate founded in 1847 that has a market cap approaching $90B dollars—not exactly fly by night technology.

Patient Anecdotes are Innocuous: Some patients have reported varying numbers, but comparing two systems to each other at different times, using different blood samples, and different processes is not scientific—even if one test is done in a lab. In order to know which machine is more accurate you need to compare both to a calibrated reference system and the appropriate ISO standard.

Dozens of articles have been written insinuating that Theranos is dangerous, but in the outrage there seems to be very little in the way of objective evidence. Sure, a few doctors have gone on the record calling the technology into doubt. The FDA spent over a week inspecting Theranos, and while they found processes that need to be improved, they apparently didn’t find evidence of safety risks that merited closing them down. And remember, the FDA had no qualms about severely hampering fellow disruptor 23 & Me.

Are There Valid Criticisms Of Theranos?

Absolutely. But most of the criticisms the company face have to do with an inability to properly convey a message.

Would Theranos Have Been Better Off in Boston?

Boston’s software scene took a massive hit when Paul Graham relocated Y Combinator from Boston to Silicon Valley, but it has never been stronger in biotech.

There are hundreds of biodiagnostic companies in Boston, both startups and Fortune 50 multi-nationals, and the spillover effects from this concentration are real. In the same way you find the best hackers in San Francisco, Boston is home to the best scientists, healthcare savvy communicators, and investors.

The healthtech cluster in Boston also largely stays away from the tech echo chamber. They know there’s a real risk in turning on the hype machine. It got Holmes huge amounts of press, but the general public takes health standards very seriously. The minute there’s a question around a diagnostic or treatment, even if only backed by circumstantial evidence and innuendo, it becomes a PR nightmare, as Theranos is learning first hand.

Nonetheless, some of these companies outside the Valley would be wise to study the Valley’s approach to evangelism to raise more money and at higher valuations.

IT and Biotech Unicorns are a Different Breed

Theranos stands out from the rest of the Billion Dollar Club as one of a few biotech companies. It gets more press than its biotech contemporaries and is often mentioned alongside companies like Uber and Airbnb. But there’s a lot of difference between these startups.

Theranos has real technical risk. There are serious question as to whether the single drop of blood can provide diagnostic equivalence to conventional test techniques. The company is over twelve years old and haven’t cracked it—this is a very challenging technical problem. Furthermore, my experience with biotech innovation is that timelines are far less predictable than software or even hardware.

Perhaps the Billion Dollar club needs to add a volatility index due to the technical risk of this company relative to the many others. It’s a lot harder to value the underlying tech at Theranos because it’s highly technical and not public. Unlike Airbnb or Uber, which consumers can see and evaluate the product themselves, Theranos is much closer to a research project. I’m not arguing whether or not it’s worth $9B—I’m simply pointing out that the metrics to evaluate this business are far different than virtually all the others on the list.

Theranos Is A Good Reminder Technology Companies Can Fail

There has been a generation of entrepreneurs, as well as VCs and journalists, that have known a world without execution risk. Innovation outside of code compilers is messy. Read the history of DuPont and you’ll find a litany of ambitious young chemists who literally blew themselves up mixing unstable elements. The early days of progress in the pharma industry are marked by catastrophes like Thalidomide that left a generation of children deformed.

Today our concept of tech failure is the “Fail Whale.”

Software has almost no “will it ever work” risk, but rather much more risk around customer adoption. Conversely, a test that can detect say cancer more accurately or sepsis more quickly certainly would be demanded by the marketplace if the clinical evidence is shown.

Developing hardware is at least 10X harder than software and biotech is 10X harder than hardware. It’s one thing to spend all night looking for a bug in your code, try searching a 30,000 square foot clean room for rogue bacteria that have been confounding experiments.

The pharmaceutical industry spends billions of dollars every year investing in drugs that just don’t work. It might be that studies show inconclusive results, and they get killed. Or that they kill patients, and are canceled. Billions of dollars, millions of manhours all lost as a matter of course. So unless and until there is serious evidence of Theranos putting patient’s health at risk, give Ms. Holmes a break.

I’d rather have Theranos and those like her out in the world solving these problems. Go on Ms. Holmes, Mr. Musk, and others. Let’s find those breakthroughs, even if we stub our toes, or prick our fingers, in the process