While there has been high profile U.K. government backing for furnishing the nation’s youth with digital skills in recent years, including a requirement in the English national curriculum to start teaching coding to primary age children, new research from comms industry regulator Ofcom suggests a parallel push to teach kids to be much better critical thinkers in our information-overloaded era is also desperately needed.

As it stands, a growing segment of the nation’s youth is far too credulous when it comes to the media they are consuming online, with Ofcom finding that British kids sometimes lack the understanding to decide whether the digital content they are viewing is true or impartial.

Its latest media use and attitudes report, which surveyed the views of U.K. children and parents in 2015, charts a rise in trust in online information among kids, with nearly one in ten of eight- to 15-year-olds apparently believing the information they encounter on social media websites and apps is “all true” — a doubling of the rate from last year’s report.

In one sense this is hardly surprising, in an era of increasingly blurred lines dividing editorial content from marketing and advertising. Not to mention the systematic appropriation of user generated content by the likes of giant ad-powered social media platform businesses, such as Facebook, to use as a trusted backdrop in order to dripfeed advertising to users.

But all the more reason, then, to teach kids to be more critical about the digital information they are being fed. Not that this is something the government appears to be prioritizing. Rather it continues to focus attention on the needs of digital businesses, such as funding free online courses teaching the kind of skills tech employers seek — such as social media marketing training. Media literacy? Not so much.

Incredibly Ofcom’s research found that one in five online teens (twelve- to fifteen-year-olds) believe information returned by a search engine such as Google or Bing must be true. Yet only a third are able to identify paid-for adverts within these search results.

Ofcom also found that U.K. kids are increasingly turning to YouTube — another platform owned by ad giant Google — to seek out “true and accurate” information about the goings on in the world. Nearly one in ten (eight per cent) of online kids identified YouTube as their preferred choice for this kind of info, up from just three per cent in 2014.

Yet only half of the 12- to 15-year-olds who watch YouTube are aware that advertising is the main source of funding on the site, and just under half are aware that video bloggers can be paid to endorse products or services.

Truly we are living in a golden age for marketing and misinformation.

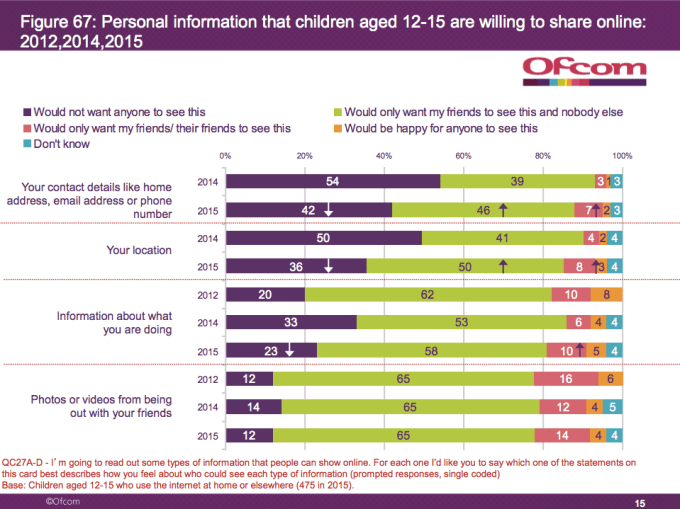

The research also suggests the nation’s youth is generally becoming more comfortable with the notion of sharing personal information online — again, hardly a surprise given how they are being groomed to do so by the social media platforms that rely on user generated content to power their businesses.

Ofcom found that fewer teens than last year’s study would not want anyone to see their content details; location; info about what they are doing; and photos and videos from being our with their friends.

That said, the research also found teens are increasingly stating they want this type of personal information sharing to be with their friends only — suggesting growth of a more nuanced position on privacy, such as perhaps kids preferring the more bounded info sharing enabled by messaging apps, for instance, vs the broader social sharing platforms where their parents may also be present.

The full Ofcom media use and attitudes report can be found here.