Israeli startup Dojo-Labs is launching out of stealth today after more than a year working on its connected home security device. No, not another Wi-Fi spy camera trying to engender a sense of vicarious paranoia in the buying public to convince folk with money to burn they need to ceaselessly surveil their property (and/or family).

Rather this startup has it eye on securing the connected smart home from the threat posed by, well, all the devices that comprise the connected smart home.

Dojo’s first (eponymous) device — available for pre-order now, with a shipping date of early March 2016 — aims to create a consumer-friendly security and control interface at the network layer that the company claims is capable of spotting and blocking anomalous behavior by connected devices on your home network. Whether that behavior is down to hackers trying to infiltrate your devices remotely. Or your devices trying to send your personal data somewhere they shouldn’t be, surreptitiously — perhaps by manufacturer design (hello smart TVs!).

The network monitoring gizmo will even warn you if you’re about to browse to a malicious URL on your laptop or smartphone when using it on your home network as it parses for known problem URLs at the DNS request level as part of its security duties.

And the idea is to do all this in a way that does over-burden the mainstream consumer user with endless gnomic security notifications. “We really want to give our customers peace of mind without needing to be a security expert,” says co-founder and CEO Yossi Atias. “We don’t want to turn anyone to become the CSO of his own home. He’s not working for us; it’s the other way, we work for him.”

“It doesn’t require any software integration with any existing product,” he adds, explaining how the Dojo hardware works. “It’s a pure over-the-top solution, so it’s a network based solution. It’s not a host based solution. We don’t need to install anything on any existing device.”

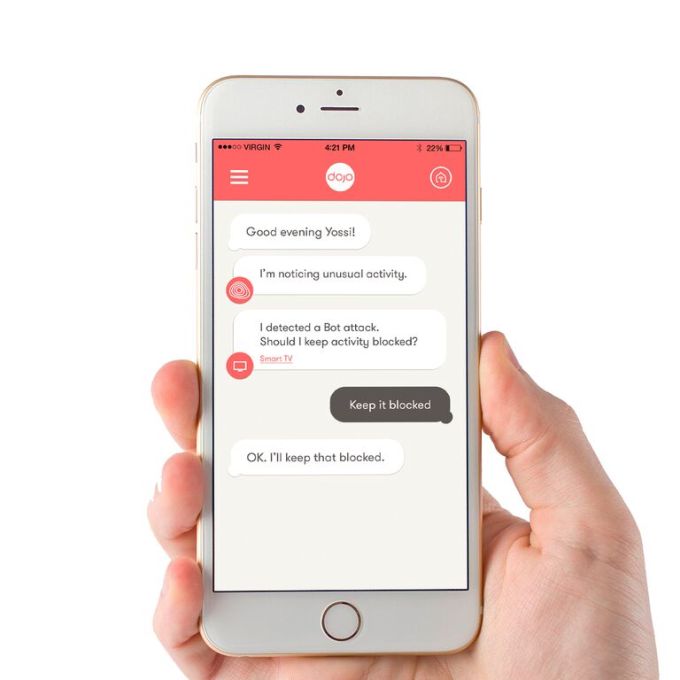

With simplicity in mind the app interface linking the Dojo with the user works like a chat thread in a messaging app. Full marks for tapping the mobile zeitgeist via a spot of savvy UX design.

So how exactly does Dojo work? All traffic on your home network has to be routed via the Dojo in order for it to perform its watchdog function, so the box plugs into your existing Wi-Fi router via an Ethernet cable. Which means you have to be comfortable trusting the startup with metadata-level visibility into all activity on your home network.

But on the trust front Atias argues that users of Internet of Things devices really have two choices at this point: either trust a dedicated security company like Dojo-Labs to keep your data safe. Or trust lots of probably not very secure connected gizmos built by non-security startups and — potentially — have to trust the entire Internet with your data.

Once plugged in to your Wi-Fi router, the Dojo generates a view of all connected devices on your home network and continuously monitors their activity — sending device activity metadata back to the startup’s cloud platform for analysis and the detection of “network wide phenomena”, as Atias puts it — using proprietary statistical tech and mathematical models coupled with machine learning algorithms. So the platform is designed to get smarter as it gathers more metadata from more types of connected devices and more usage of those devices. The metadata it sends to the cloud is encrypted with the startup’s own private key, according to Atias.

“The Dojo… takes control over the full network function in your home network and from that point onwards every communication that goes out and in from your devices to the Internet, or among the devices themselves, go through our device,” he says.

“The device analyses the data streams — not the data itself, so we’re not looking into the user data, only on the metadata related to the device themselves in terms of how they behave — and this is how we do everything from the very basic function from a full home [connected device] discovery and then ongoing detection and mitigation of cyber related risks, both on the security side but also the privacy breaches side,” he adds.

The basic premise of Dojo-Labs’ anomaly detection model is that most Internet of Things devices are designed for a specific function. A smart lock is for locking and unlocking a door, for instance. A smart thermostat should be controlling your heating, and so on. So spotting when an IoT device is doing something odd or bad is a case of identifying deviation from the normal behavior for that particular device. (Albeit, there are a lot of IoT devices already; some 4 billion now — and there will only be an awful lot more of them; as many as 20 billion are projected by 2020).

“When it comes to IoT devices they were designed to do a very, very specific function,” says Atias. “The fact that we collect this metadata to the cloud enables us to create some kind of crowdsourced security engine. So assuming we have a lot of users using the same camera or the same smart TV or the same smart alarm or smart lock there is no real reason — I’m talking now about network behavior, not content wise — that one device will behave different from the other, because they’re all running the same software, which is not something the user can change.

“They were designed in the same way, they perform the same function. Once we identify that one of the devices of the same nature is actually out of the scope of that profile that’s a good indicator of things that are going wrong.”

He talks up not just the security aspect but the pro-privacy angle of using Dojo, pointing to — for example — those problematic smart TVs that snoop on users by design to harvest behavioral data for manufacturers, in some instances without offering the user the ability to opt out. The Dojo will give consumers a control layer over such devices, he says, adding: “We believe that everyone deserve a right for privacy and deserve a right to control the level of data sharing and information sharing… That’s really up to the user.”

In the coming three to five years any product going out of factories will be connected by default.

“In the coming three to five years any product going out of [consumer electronics manufacturers’] factories will be connected by default,” he adds. “So as a consumer… if you want to buy anything from a refrigerator or washing machine or vacuum cleaner or anything — not to mention cameras and that stuff — they are all connected… All the vendors have decided this is the next big thing.”

The Dojo’s anomaly warning system operates via a traffic light style color code — with only a red alert requiring direct user action, such as asking the user to specify whether a new device that has just appeared on their home network should be blocked or not — it might be the latter if it’s a guest they just gave their Wi-FI password to, for instance. Or it might be a hacker trying to break into their stuff. (The Dojo can also be used to control guest access, to, for instance, allow one-time access or function-limited access, depending on what the master user prefers.)

The color coding system extends to the Dojo hardware itself, which comprises two pieces: a fairly standard-looking network monitoring box that needs to be plugged into the router, and a rather more unusual pebble-shaped connected object that can either rest on the router, in its plastic indent, or be moved around the house to stay in line-of-sight for the humans.

What’s the pebble for? It’s to provide another visual notification for when the system needs a little human attention to address a particular anomaly it’s detected — so an alternative notification medium for users who might not want to be nagged by too many notifications on their phone, say. Given you only really need to access the Dojo app to deal with a red alert, if the pebble is glowing green or even showing an orange warning you know you can leave your phone alone.

“We wanted to take a very abstract topic like security and put it into a very simple, nicely designed device that everyone can understand so you don’t really need to know anything about it — you just see the colours and you know ‘I’m safe’/’not safe’,” he adds.

The original idea for a smart network monitoring device to manage all the connected devices in your smart home and on your home Wi-Fi was inspired by Atias’ teenage daughter — who he noticed had taped over the webcam on her laptop after a talk at her school about how to protect devices from being hacked.

“For me it was kind of a point when I figured out well it’s a bit weird; we use the most primitive technology to solve a modern technology platform. With the new era of smartphones where people have a lot of devices with different sensors and different data capturing capabilities — anything from microphones, cameras and sensors, it doesn’t make sense going all over and putting band-aids on each one of them to avoid any data breaches or someone going into your most private, intimate zone.”

Security has to be done by design. So that’s the reason we have standalone, external hardware which is totally independent from the rest of the components of the network.

But what’s to stop hackers targeting the Dojo itself? ‘Security by design’, says Atias, arguing that rival security devices such as Luma which offer network control features packaged into a Wi-Fi router are flawed because the Wi-Fi router itself can be compromised if the user does not set it up correctly. The Dojo avoids any such human error by being sealed off from even well-intentioned tweaks. It auto-updates, asking the cloud platform for its own updates, and is port-less, bar the single Ethernet port to connect it to the router. So it’s designed to keep outsiders from getting in.

“Security has to be done by design,” he argues. “So that’s the reason we have standalone, external hardware which is totally independent from the rest of the components of the network… And it’s designed in a way that it’s totally unaccessible. Even if you take it as a hacker and you try to hack into it physically, even by breaking it, there is no way you’d ever get access to its operating system and to its code. This is how we designed it.

“It’s our own hardware, it’s not just a Raspberry Pi running some kind of software. We designed everything from scratch. So for example it doesn’t have any redundant interface, it doesn’t even have the interface that a lot of vendors forget in their products… We don’t allow any access to our device. Even our cloud cannot communicate with our device, it’s always the other way… It doesn’t listen to any requests coming from the outside.”

Ok, then, what about government requests for data? Pro-privacy folk might not like the idea that they are opening up a portal for overreaching government agencies to harvest the routine substance of their domestic digital life. “We don’t have any ties or any interactions with any government organization. We are a startup,” says Atias, although he confirms it will abide by the law of any country it is operating in — so given it holds encryption keys it could indeed be served a warrant to decrypt and hand over user network activity metadata.

“We are not familiar that we are obliged to provide any data to anyone without a legal procedures, like any other company. But certainly it’s nothing by design,” he adds.

Another slight issue with Dojo’s pro-privacy pitch is the structure of the system undermines the privacy of users on the same network by creating a master user — meaning someone in the family has absolute visibility of all devices on the network and, presumably, the ability to control/block the devices of other network users at will.

“Eventually there is one master owner of the app, and he needs to decide to whom he wants to give access to this control. What you certainly get is really the overall kind of view of your home,” he admits.

If you’re happy to trust an outside company with visibility of activity on your home network — albeit one that professes a strong pro-privacy position — and okay with handing control to a single “master” user of the app within your household, then Dojo’s approach to shoring up the creep, creep, creep of not-so-secure-by-design connected devices might help you sleep a little more peacefully amid all the hums, buzzes and bleeps of your smart home.

Price wise, the device is being offered at $99 during pre-order, initially targeting the U.S. market. That discounted pre-order price includes one year of subscription service. The Dojo will continue to work once the subscription lapses, but with reduced functionality. Those choosing one of the monthly packages can expect a greater level of interaction from the system and more security updates, according to Atias. He says there will be a range of subscription options to choose from once the first year’s bundle comes to an end, starting at $7.99 per month.

What’s left to do to get the Dojo into buyers’ hands at this stage? “We have the product already, we have already few hundreds of devices in production for friends and family so it’s really about finishing our software cycle after it was deployed in real houses,” adds Atias, noting the team already pulled in $1.8 million in seed funding earlier this year, led by Glilot Capital Partners along with some private Silicon Valley investors.

“There is a huge industry that evolved around less than two billion connected smart devices… laptops, tablets etc. They’re going to be 20 billion ‘not-smart operating system’ IoT devices. Those devices are going to be connected and someone needs to take care of their security and privacy. And this is what we intend to do,” he says.

“We don’t envisage millions of users in the first year, certainly not even in the second one. It will go by tens of thousands, and then hundreds of thousands. And within five years hopefully millions. That’s the plan.”