In response to calls for stronger action on hosts that aren’t casual users, Airbnb said it would start sharing some data with governments and getting hosts to agree to a policy of listing only their permanent homes.

Here’s what Brian Chesky said in a post today:

Today, we’re taking the next step to turn these principles into concrete actions by releasing the Airbnb Community Compact. There are three commitments that are part of this Compact:

- We are committed to treating every city personally and helping ensure our community pays its fair share of hotel and tourist taxes.

- We are committed to being transparent with our data and information and we will help cities understand the home sharing activity in their community while simultaneously honoring our commitment to protect our hosts’ and guests’ privacy.

- In cities where there is a shortage of long-term housing, we are committed to working with our community to prevent short-term rentals from impacting the availability of long term housing by ensuring hosts agree to a policy of listing only permanent homes on a short-term basis.

Unfortunately, there’s not a ton of information on what this all means. When I asked company spokesperson Nick Papas for more information on what kind of data would be shared, he replied:

Our community — and our business — are stronger when guests are staying in primary residences and interacting with hosts. We will be releasing anonymized information about the profile of the community — including information showing how many hosts are sharing permanent homes — so cities can see if we are walking the walk. Our experience is that our community is very good about making decisions in the best interest of their communities.

Papas stressed that the data will be anonymized to protect hosts’ and guests’ privacy.

But the issue is if that Airbnb knows how many hosts are sharing permanent homes, they should have a sense of which hosts are not doing that and they should actively block or require them to undergo extra hurdles to register with the city government.

Eric Schneiderman, the New York State attorney general who subpoenaed financial data on hosts last year, called today’s statement a “transparent ploy by Airbnb to act like a good corporate citizen when it is anything but.” He added, “The company has all of the information and tools it needs to clean up its act. Until it does, no one should take this press release seriously.”

Last year, Schneiderman subpoenaed data that showed that 6 percent of hosts were generating 37 percent of the platform’s revenue in New York City. Airbnb has disputed this interpretation of the data while Schneiderman’s team has argued that the subpoena didn’t even go far enough.

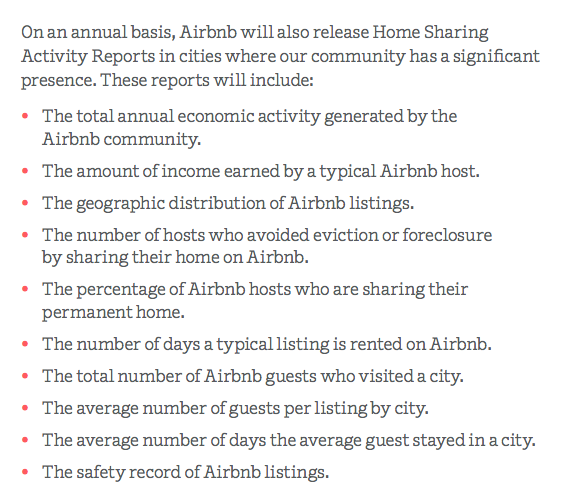

Here’s some of the data Airbnb says it will now release in annual reports. As you can see, many of the data points are averages, which no one necessarily cares about because most hosts are casual, just like Airbnb says. It’s the commercial hosts that city governments and housing activists are worried about and who likely happen to be some of company’s most lucrative sources of revenue.

While Airbnb successfully fought off Proposition F in San Francisco, it may still face tighter regulations with progressive Aaron Peskin elected to the city’s Board of Supervisors. The company is also still embroiled in an ongoing regulatory process in New York City, not to mention numerous other cities across the United States.

There are lots of other kinds of compromises cities and the company could work out. Maybe hosts should be able to freely list spaces without being registered for up to 90 days in a single calendar year. But if they go over that and don’t happen to be registered, maybe the hosting platforms should cut them off and only re-list them if they have the appropriate registration.

I’ve written about the difficulty of enforcement here. In San Francisco, we have four enforcement officers (soon to be six) that can only really reactively respond to neighbor complaints because they don’t have any visibility into the size or growth of the market, which had slightly less than 10,000 units listed on Airbnb in the last calendar year. Then, on top of that, we don’t know the activity on VRBO, Craigslist or the dozens of other platforms. City enforcement officers don’t have any accurate data and only slightly more than 700 hosts have registered.

It’s in Airbnb’s interest to have a settled and stable pattern of regulation across its major markets before it goes for an IPO. But until U.S. city governments and the public feel comfortable that the company has cut out or eliminated commercial actors that have multiple properties or are converting permanent housing to short-term rentals, this will be an open case.