Radical technologies around the world may soon overhaul the field of disability and immobility, which affects in some way more than a billion people around the world.

MIT bionics designer Hugh Herr, who lost both his legs in a mountain climbing accident, recently said in a TED Talk on disability, “A person can never be broken. Our built environment, our technologies, are broken and disabled. We the people need not accept our limitation, but can transcend disability through technological innovation.”

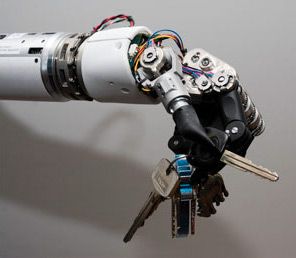

His words are coming true. Around the world, the deaf hear via cochlear implants, paraplegics walk with exoskeletons and the once limbless have functioning limbs. For example, some amputees have mind-controlled robotic arms that can grab a glass of water with amazing precision. In 15 or 20 years, that bionic arm could very well be better than the natural arm, and people may even electively remove their biological arms in favor of robotic ones. After all, who doesn’t want to be able to do a hundred pull ups in a row or lift the front end of a car up to quickly change a flat tire?

The same radical improvements will happen with eyesight. Already, blind people can see some things better than the natural eye with robotic technology made possible by the Argus II. In 15 years time, expect bionic eyes to be electively installed in our eye sockets, as they will be superior to human eyes. And wheelchairs? They are likely going the way of the dinosaurs. Expect some wheelchair companies to go bankrupt if they don’t diversify over the next decade as exoskeleton technology becomes commonplace.

Soon, I think many people will have exoskeleton suits — disabled or not. In fact, some people will probably have different models. Some suits will be for sports, some for wearing exclusively on the battlefields (such as the Ironman suit) and some will be just for having crazy sex in positions most people never thought possible.

All this is great news for the hundreds of millions of disabled people around the world, many who are suffering and are mentally depressed as a result of their handicaps. Transhumanist technology is revolutionizing the way we deal with physical disability. And I couldn’t be happier about that fact. I hope every handicapped person in a wheelchair gets out of it and into an exoskeleton suit. And I hope in two decade’s time, improved stem cell technology will get their spines and other nonfunctioning body parts back to ideal health and strength.

The medical field will probably have to come up with new terms to define this post-disability age.

Futurist and writer B. J. Murphy recently emailed me, “In the future where mostly everyone is able bodied, how might we define ‘disability?’ Surely, as the disabled become augmented and/or enhanced, our current definition of what makes someone disabled — not able bodied — will be done away with altogether. Though, how do we then consider those who are, albeit able-bodied, not augmented or enhanced? Do we change the definition of ‘disability‘ as something which someone simply is when not modified with advanced technologies?”

The questions are certainly interesting and important. Could we one day be a species that sees itself as born “not fully able-bodied,” or even technically disabled before modern technology has had a chance to radically transform us? Exoskeleton suits and bionic boots will probably allow us to run as fast as cheetahs in the near future, and bionic eyes will allow us to see far more of the existing light spectrum than human eyes can, so such ideas are possible.

Continuing with this line of thinking, people who don’t use smartphones, own and drive a car or participate in social media are sometimes seen at a definite disadvantage in the 21st century — one that some might call a social handicap and that some employers would find unhireable.

On the flip side, though, some people will probably be turned off by too much augmentation and technology in their lives, even when it helps their disabilities. And those people may refuse treatment or help. That is, of course, their right to do so, and it will be important to respect their feelings and prerogatives. But many others will welcome radical technology to change their lives and physical states.

“It’s not well appreciated,” said, Herr in his TED Talk, “but over half of the world’s population suffers from some form of cognitive, emotional, sensory or motor condition, and because of poor technology, too often, conditions result in disability and a poorer quality of life. Basic levels of physiologically function should be a part of our human rights. Every person should have the right to live without disability if they so choose.”

Regardless of how people accept such enhancing technology, I’m betting in the future, the definition of disability will change dramatically. It will be based on what kind of improvements people accept and what kinds they do not accept. The “disability” definition will probably change as much as the definition of death has been changing over the last decade. With suspended animation now being practiced in an American hospital in Pittsburgh, doctors can keep people completely dead for a few hours, then revive them back to life. In five years, that “few” hours are likely to become 24 hours.

And in 10 years, that brain-dead suspended animation state could become weeks or even months (which futurists hope will be useful for space travel). Like the changing specter of death, the challenge of physical disability upon the human race will also change. If the species allows these changes, we may overcome physical disability completely.

The medical field will probably have to come up with new terms to define this post-disability age that transhumanists aim to usher in. Those new terms will be welcomed words for many of the hundreds of millions of disabled people around the world eagerly waiting to regain their full physical possibilities.