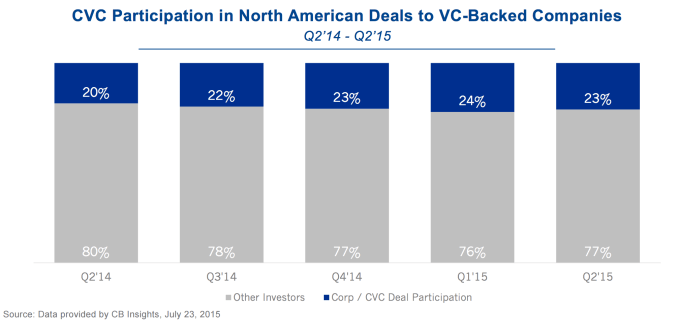

When it comes to raising money in the U.S., corporate venture capital is seemingly synonymous with “Plan C.” If you can’t raise money from top-tier firms, you move on to Plan B, second-tier firms. Failing that, Plan C is corporate.

There are exceptions, but corporate does tend to be the last resort: The place you go when your company has been shopped, or your valuation is so high that the only investors insane enough to write you a check have hoards of “dumb money” to spend.

“They suck!” is how Fred Wilson at Union Square Ventures put it. “They are not interested in the company’s success or the entrepreneur’s success. Corporations exist to maximize their interests. They can never be menchy or magnanimous. It’s not in their DNA, and so they suck as investors.”

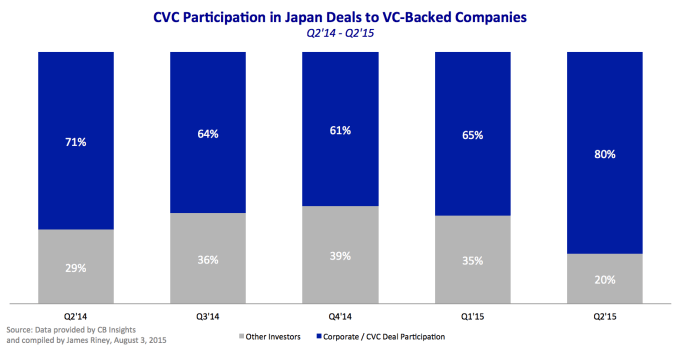

Raising from corporations might not be ideal in the U.S., particularly in the Valley. But in Japan, tech entrepreneurs don’t have the luxury of balking at corporate venture capital (CVC).

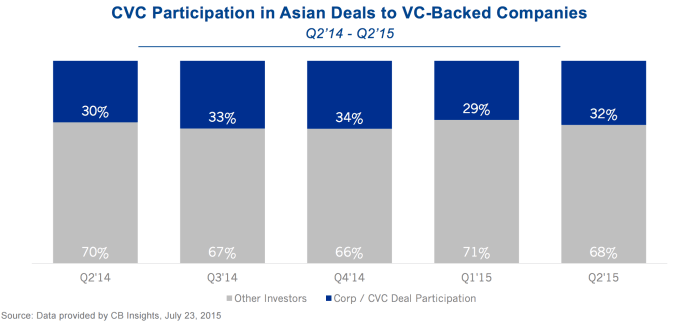

In many ways, venture capital is fundamentally corporate capital, not only in the form of CVC, but also in the form of limited partners for independent funds. While a significant majority of the money in the U.S. comes from institutional investors, such as pension funds, endowments or fund of funds, in Japan, a significant portion comes from corporations.

The disparity comes from the fact that Japanese investors tend to be much more risk averse, and venture capital is widely considered too risky an asset class to place money. And, unfortunately, returns haven’t quite reached Silicon Valley altitudes to get over this aversion.

As a result, there is significantly less risk money available to entrepreneurs. In 2014, about $960 million was invested in venture capital, versus $48 billion in the US — a difference of 50x. For angel investment, the difference is about $1 billion to $24.1 billion. In other words, there was only about $1.96 billion available to Japanese entrepreneurs. That’s almost the size of Andreessen Horowitz’s fifth fund.

So why do Japanese corporations invest in startups? The reasons are not so dissimilar from corporate investors in other countries. Corporate investors’ sole purpose is not financial return. From a management perspective, the corporate venture arm is seen as an R&D or corporate development expense.

R&D needs are served by being able to keep an eye on the newest trends, and detect what could affect their core businesses before it is too late to act. On the corporate development side, it is a mechanism to spot companies to acquire, as well as build relationships with promising companies in hopes of partnering with them in the long run. In essence, it doesn’t really matter whether they view VC as risky or not: financial return is not the primary goal.

Interestingly, because a lot of the money for startups comes from corporations anyway, there isn’t a sense that corporate money is somehow inferior to independent money.

In fact, in many ways, raising money from established companies with strong brands is a better signal to the market. In a country that is inherently risk averse, the backing of a brand-name company conveys stability, and that stability helps tremendously.

When you are a scrappy no-name startup, it is much easier to persuade clients to go with your solution if they’re convinced that you will still be around in a year. The same goes for when you’re trying to convince top talent to jump ship. The corporate backing gives the illusion that your startup paddle boat won’t sink in the entrepreneurial storms ahead.

Perception all depends on where you are standing. In the Land of the Rising Sun, some corporate investors are the Sequoia’s and the Andreessen Horowitz’s of the venture world. As counterintuitive as that may sound, it probably isn’t the first unique thing you’ve heard about Japan.