I remember clearly the first time I saw Caspar Bowden. It was spring 2011, and he had just shot a bolt of electricity through a dusty seminar on online privacy with a passionate invective on sham anonymization of datasets that went into idiocy-explainer levels of detail about how current U.K. data protection law was being a complete ass.

“You can start with external sources of data where you can get a few phone numbers, a few relationships, you look for some patterns and then very quickly, like pulling at the threads of a sweater, you can reidentify the whole lot,” he railed from the stage.

The specific database example he cited was, he said, “the most significant privacy breach” he’d “ever heard about, that this country has suffered” — ramming his point home with mesmerizing conviction.

“It’s never been reported, it’s never been investigated,” he added, tone simmering with righteous rage.

This lecture was delivered with the U.K.’s ICO himself, Christopher Graham, sitting on the same stage — obliged by the seminar’s panel structure to listen as his office was berated in public. Bowden, who was still chief privacy adviser for Microsoft at this time, took full advantage of the opportunity and pulled no punches.

He also used his on stage turn to sound a visceral warning about the risks posed to privacy by smart meters.

“Databases will be created about your microscopic consumption inside your own household and this could mean, for example, that somebody could build a statistical model which would have a pretty good idea, two years before you might know, you were going to get divorced,” he warned.

Point forcefully made, point taken.

I left the event to file a story on his comments, and was surprised and delighted when he subsequently tracked me down, months later, sending an email commending me on my superlative “accuracy” in reporting what he had said — while simultaneously berating other media outlets for failing to do their duty when it came to accuracy and data protection.

It was clear his worldview divided cleanly into extremes. But amid the regulatory morass of data protection, and when trying to define the murky boundaries of privacy, being able to apply a filter that allows you to perceive the divide between right and wrong is a gift — and he had that gift in spades.

The need for a robust line of defense around the information generated by individuals’ lives has become a lot clearer in the years since Caspar’s turn on that stage, in this post-Snowden era. His was one of the few voices shouting about the huge and growing risks to privacy — from cloud computing, from big data, from connected devices and increasingly interwoven datasets — when few ears were listening.

*

I remember clearly the last time I saw Caspar. It was winter 2014. He had come over to London from Brussels to hear MEP Claude Moraes giving an annual lecture on behalf of the Centre for Research into Information, Surveillance and Privacy at the London School of Economics.

I saw him come in, bundled up against the November chill in a long coat. I thought he looked older, a little weary. This time he sat in the audience. But even from his place among the listeners the fight had not gone out of him. He spoke up on several points, with his usual sharp delivery and indefatigable conviction, his seat now his soapbox.

Moraes’ lecture was far more soft-toned and conversational than any Caspar would have given on the threat to human rights from overreaching state surveillance. Moraes of course has the politician’s gift for soft tones, for measuring and weighing words in the moment of delivery to sense how the listener is taking them and adjust accordingly. Caspar’s conviction allowed no such quavering, no such mutable margins.

He saw, he spoke, he decried.

It’s a measure of the man that just sitting in an audience of his peers he commanded attention. Moraes spent a good deal of time directly addressing him during the lecture, commending him on his tireless campaigning on surveillance and couching the time, pre-Snowden, as “Caspar’s data protection dark ages”.

It’s a small comfort to those that knew him that he lived through that darkness to have his warnings heeded. But he would be the first to point out the privacy war is far from won. That battle rages on.

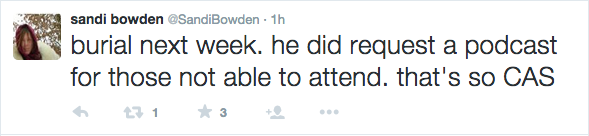

We need more of Caspar’s kind. But now we have one less.