Editor’s note: Tadhg Kelly is a games industry analyst, design consultant and the creator of leading blog What Games Are. He is currently writing a book called Core Game Design. You can follow him on Twitter here.

It’s rare that I get angry at Apple but this week I did, loudly, particularly on Twitter. Normally I’m a defender of the company or occasionally object to something it’s done in a “it means well but made a mistake” sense, but this was different. I’m referring to the banning of historical games containing the Confederate flag from the App Store, largely on the same reasoning that other stores like Amazon did with Confederate merch.

It made me furious, even though the ban was later toned down, not because I’m a Confederate supporter. I may live in Seattle but I’m Irish. The American Civil War is an interesting item of history to me but not an issue in which I have a stake. In the wake of the Charleston shootings I fully understand why that flag is a symbol with negative sentiment to many and I’m in agreement with Bree Newsome’s act of civil disobedience to remove it. I’m an unequivocal supporter of equality for all, of equal rights and treatments for minorities, for the marginalized and the disenfranchised, and for sensitivity to culture.

But there’s a line between the arts and reality. In the real world we should remove and tone down the offensive for reasons beyond political correctness. We do it for sensitivity, for inclusion and for the promotion of multiplicity. However in arts we often use these symbols for purpose. Take the swastika for instance. It’s thoroughly offensive in the real, but in the arts it has value. We don’t airbrush it out, otherwise how are we to remember, to learn? In the right context and the right presentation (from Schindler’s List through to Ingluorious Basterds) symbols like the swastika have a value beyond who they represented, in effect becoming their opposites.

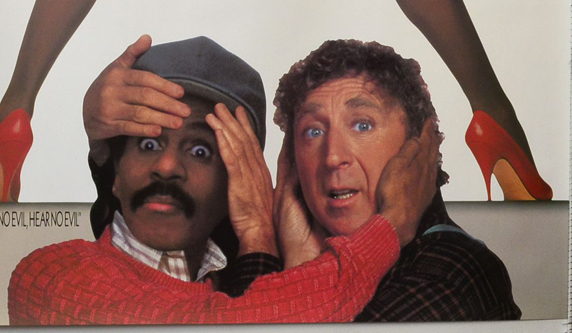

This is why media are usually considered a protected class and for issues like free speech to be considered as part of the decision to support or deny their sale. Amazon may not sell Confederate flags but it will sell you civil war movies that have that flag in them because that’s different. The reason I was so mad? Apple’s showed once again that the company doesn’t consider games in the right way. It took action against games that featured these symbols but not against any other media available on their stores. Accurate historical games got banned but not Primal Scream’s Give Out But Don’t Give Up. Not John Dooley’s Confederate War journal. Not even the Dukes of Fricking Hazzard. Apple singled games out and effectively said that games are not media and games are not speech. That in 2015, 50 years after their invention, games are not equal.

What made me mad was the double standard, the singling-out of a medium that is defined as a medium by the Supreme Court, and treating it as lesser. What made me mad was that this was yet another reinforcement that games are not considered as culture in a variety of venues that really ought to have copped on by now. What made me mad is that said venues are happy to take the billions that games earn but still treat them as barely more acceptable than porn. What made me mad was that between the action itself and the subsequent supportive commentary from numerous sources that a lot of people still don’t consider games as valid vehicles of free expression.

In 2015 games are still more censored than any other medium in the West and it stinks. Apple doesn’t tell a book author to change her text after publishing, a musician to edit his lyrics or a movie to sanitize itself. However the App Store routinely bans satirical games. The App Store bans games that artistically use nudity. Moreover the App Store often issues these bans in retrospect, after a game is already live and often months afterward. The company demands changes to content or else, placing the financial prospects of developers in jeopardy largely on inscrutable (and typically political) whims that none can question. And does it offer to pay for those changes? Of course not.

This stuff matters. In 2015 more artistically minded game developers are finding it harder to get a hearing, to rise above the noise of an industry salivating over numbers or YouTubers bitching about DLC and console specs, making comedy videos or barely concealed conspiracy rants. The most experimental voices in the games scene are often people who also identify with marginal cultures (LGBT etc) and yet the message from companies like Apple is that their medium of expression is not equal. They may say they support LGBT but the App Store probably wouldn’t publish Anna Anthropy’s Lesbian Spider Queens of Mars. But I can buy Tenacious D’s Fuck Her Gently right now on iTunes for $1.29.

Games-as-art is under threat everywhere. Last year’s Gamergate crapfest atomized many an indie game maker trying to use games for something more. A variety of other similar nonsense across the Internet confirm that the status of games-as-art feels on the verge, more so than it has for a generation. There’s a considerable movement all across the spectrum to push games back toward the status of consumer products rather than art, to be fun engines and diversions only and to sideline their more interesting and experimental voices. We’re losing something important as a result and the venues that could be active agents of change (like Apple) are not helping.

Here’s an example of the knock-on effects of the state of things today: In the same week as this flag issue, avant garde Belgian studio Tale of Tales announced that it’s basically done. As a tiny studio it had always been concerned solely with the experimental and made interactive game projects that would not be to everyone’s taste. As such had been reliant on grant money, as many artists are, but that’s been drying up. So they were left with the choice of attempting to be more commercial, which was not their wheelhouse at all and they failed. Now they’re finished, and it is a great loss to the community of game makers. The studio’s games have been very influential but it just couldn’t find a platform to thrive on as none provide adequate support.

Here’s another example: Primary indie platform Steam recently announced a revision to its refund policies, enabling players to get a no-questions-asked refund for any game if it had been played for less than 2 hours. (And if it had been played beyond that point to probably give a refund anyway.) These policies are viewed as necessary in some quarters because of the negative effects of Steam’s unpopular Greenlight and Early Access systems, and are not particularly out of step with other digital platforms. However the manner in which Valve presented them is. Valve explicitly made users aware of the change, in effect educating its comparatively-expert customers to expect it (rather than allowing them to find out). Believe me when I tell you from past experience that that virtually guarantees widespread abuse. Players will float across many games and play but not pay for any of them. Who does this affect most? Weird interactive concept games that you can finish in an hour.

Many readers might say “too bad” or advocate to think of such things in fly-or-die business terms, but that’s short sighted. In most industries there needs to be an experimental space beyond the purely bottom-line. Often it’s located in academia for example, such as the way that the tech industry is closely linked with universities. In games academia has always been an ill fit for this however. There is always a tendency to twin games with social-good or education projects because that’s where the real funding is, which can have value on their own but are not exactly the same thing as pure arthouse projects. Meanwhile on the cultural side many countries have enacted regimes to help games to get tax breaks, but unlike film funding the provision of such breaks tend to be determined by commercial concerns and decided by people who come from commercial roots. You can get tax breaks to make yet another Game of War clone, but not a Luxuria Superbia.

There’s little room for the crazy, the weird and the just plain bonkers. As a result it lives on the margins, largely thriving on the benevolence of existing venues like digital stores. So actions like the App Store shutting down games on a whim, Steam killing the trickle of revenues such games might earn and so on causes untold damage. These actions tell developers that they better be conservative or else, and in combination with the giant consumerist whinge from the right wing of gamer culture the overall sentiment pushes artsy games into dangerous territory. Long story short I find myself more fearful for the future of creativity in games than for a long time.

Of course there are still examples of good to be found among the bad: In the same week as Apple’s action and Tale of Tales’ bad news, an indie game was released that everyone should play. It’s called Her Story. In it you are placed in the role of someone researching a set of video interviews with a murder suspect, digging through an archive. It’s a bold game, one that defies many conventions (using FMV, for example, which conventional developers have long considered verboten). And yes it’s on the App Store too.

And yet I have to wonder: had the developer of Her Story chosen to be even more extreme with its tale, would they have been able to get it onto major platforms? Would such experimentation have had access to an audience? Will other developers looking at its success think this, or will the prevailing conditions make them think that they can only push so far? In so doing are exciting games like Her Story or last year’s Gone Home essentially to remain held up on a “here but no further” kind of pedestal unlike any other medium, leaving games cut off from being all that they can be?

The message from the likes of Apple and Steam is currently, tragically, yes. It doesn’t have to be.