Sean Parker, who changed the music industry as a teenager and then went onto have an early and formative role in Facebook, has long had one frontier that he’s wanted to change: American democracy.

Now he, Matt Mahan, and a team of engineers and product talent who have long worked at the intersection of technology and policy, are unveiling Brigade for the first time. It’s an app they’ve worked on for the last year that’s meant to quickly get regular people engaged in articulating and debating political positions.

If that sounds like a steep order for the Millennial generation, Brigade’s team has tried to tamp down expectations. They’ve tried to make the product as simple as possible as it enters private beta this week, so that it’s easy for lots of people to pick up.

Parker repeatedly stressed that Brigade’s current form was just a beta, and the company had been actively courting feedback from testers. That’s a big 180° from the flashy, celebrity-laden unveiling of his last stealth startup Airtime. That app promised a social entertainment revolution through video chat, but flopped due to a buggy launch demo and a product few found critical to their lives. Now Parker’s back with grander ambitions to fix democracy, but a modest approach to getting there.

“The mission of the company is to empower people in their civic life and to have influence over the direction their society goes in by having them articulate and identify where they stand on issues uncover alignment with friends, get organized into groups of like-minded people and ultimately act collectively to shape the policies that affect their lives,” said Mahan, who was previously the president and CEO of Causes.

Brigade CEO Matt Mahan Interview from Brigade on Vimeo.

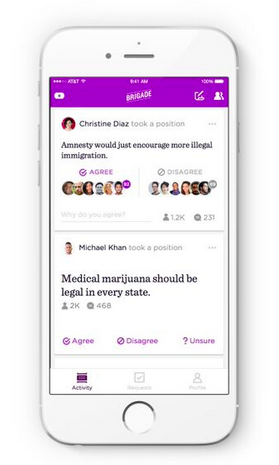

At its core are simple stacks of cards that you can agree or disagree with.

At its core are simple stacks of cards that you can agree or disagree with.

For example, a trending topic today is “Trade With Asia.” You can flip through a series of cards with statements like “Massive international trade agreements hurt small businesses in America” or “International trade deals expand opportunities for American goods abroad.” If you take a position, you’ll see a polling chart that shows the percentage of Brigade users who are either for or against your side. If you’re not sure, you can flip through reasons that argue for both sides.

Parker said they wanted to pare the experience down to its basics and take out policy makers or parties at the start. (The company stresses that they’ll be layering on a lot more features later like the ability to start groups with like-minded friends and analytics for campaign partners as they grow the user base though.)

“When we were thinking about how to engage people in politics, most people say they don’t care about politics. They hate politicians. Congressional approval ratings are at a historic low. Trust in government is at a historic low. From one point of view, the system is about as broken as it can be,” Parker said. “But when we interview users, we find that everyone has an issue they care about or something that they want to change in the world.”

Out of the 13,000 users in the private beta a test version of the app that was secretly released several months ago, the average Brigade user took 90 positions, which the company feels is a really high level of engagement.

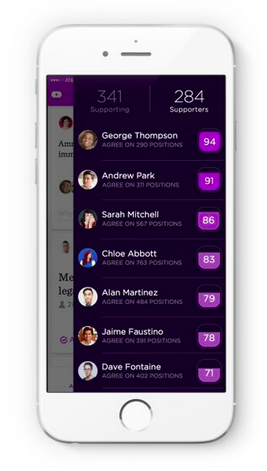

Over time as you take more positions, you’ll create a profile that you can compare against friends, colleagues and family members. So I can see the people in my network that I’m most politically aligned with.

You can also convert users or friends over to your side. “If I decide to switch my position because of a friend’s reason, they get social credit for that,” Mahan said. “That’s our highest signal-to-noise ratio.”

Although Brigade has done some early events with politicians like presidential candidate Rand Paul, the company says its political make-up ranges across the spectrum.

“A lot of people are progressive as you’d expect for a company in the Bay Area. But we’ve got quite a few folks who would self-identify on the other end of the spectrum,” said Mahan.

The big obstacles for Brigade are proving that publicly stating your political opinions is both something you actually want to do, and that you want to do on its app.

The big obstacles for Brigade are proving that publicly stating your political opinions is both something you actually want to do, and that you want to do on its app.

Exposing stances on controversial issues can cause points of contentions with friends, family, and colleagues. Many are happy to quietly vote for their beliefs, but might not want to trumpet them in perpetuity online.

If users are willing, they’re likely already able to do this elsewhere. Politics enthusiasts frequently take to Twitter, which has the scale to give them a large audience, and easy ways to get the message amplified through retweets. Broad opinion sharing networks like State have failed to capture a significant user base.

And while getting on your Brigade soapbox might be fun occasionally, becoming something users find engaging enough to consistently return to may be difficult. People tend to forget about apps they don’t use at least once a week.

Parker said that leveraging social networking to create engagement in democracy and government has long been a “fairly quixotic problem for dozens of companies.”

“But if we want to build a platform to disrupt democracy, we can’t ignore politics,” he said. “We need to meet people where they are.”

He added that Silicon Valley’s political identity is really hard to encapsulate. Lots of politicians from both parties often ask him how to engage with the technology industry.

“There is no unifying principle that animates Silicon Valley engineers and product managers and employees,” he said. “Then on the other side, there doesn’t feel like there’s a productive means of interacting with the political system. Washington couldn’t be more different in terms of the way it

it’s designed to work slowly. The Constitution was designed with the intention for the wheels of power to move slowly. What we perceive as dysfunction is a fault correction mechanism, designed to prevent bad things from happening. That tends to contradict the basic values of Silicon Valley in which we raise money, move fast, break things and get things done quickly with the hacker mentality. When you have a Washington political system that’s designed to move slowly and a Silicon Valley culture designed to move quickly, there’s going to be tension.”