Winston Churchill famously said, “Democracy is the worst form of government, except all the others that have been tried.”

Until recently, the same could be said for the factory model of education. Imported from Prussia and implemented at the urging of education reformer Horace Mann, the factory model puts kids into age-based classrooms and uses seat time to determine when they’re ready to move on to the next level.

In many ways, it’s an awful system; rigid, arbitrary and impersonal. But it’s also responsible for almost every modern innovation we rely on today. The factory model reduced the per-student cost of education sufficiently so that wealthy countries could, for the first time ever, provide free and compulsory K-12 education to all children.

Wherever the model doesn’t exist, the populace desperately wants it. Modern medicine, housing, entertainment, transportation, communication, the Internet and everything else in the modern world exist because of the factory model. That’s the good part.

Now for the bad.

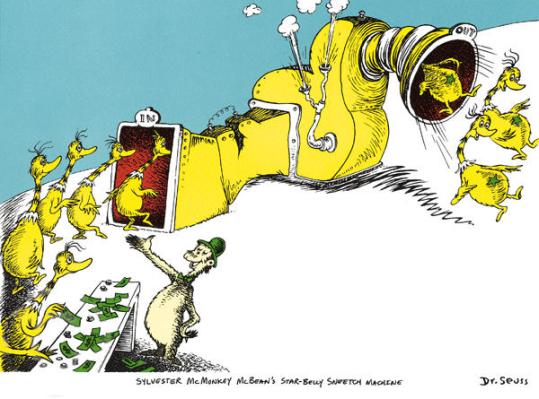

The factory model requires of children that they independently decipher the world’s largest bureaucracy — replete with invisible rules, conflicting stakeholders, perverse incentives and assembly-line product delivery. Yet they receive no user’s guide to navigate this gargantuan meat grinder.

Some kids are necessarily a better fit for the system than others because of personality, upbringing, temperament or other factors. Perhaps they thrive in highly structured environments. Perhaps the pace is just right for them. But what if a student is one of those people who thinks a little differently? What if they don’t quite conform, can’t easily control their attention span or perceive the structure of the world in their own way and at their own pace? They may be a genius, or they may just be their own dynamic personality, but they are a poor fit for the factory model.

These students have to work harder to achieve the same results as equally talented students who happen to fit the system better. Or they may not be able to achieve the same results at all, regardless of effort, intelligence and talent. Their brains just don’t work that way.

We ought to have an education system that adapts to children. Instead, we force children to adapt to the system — without giving them any guidance. If they don’t adapt, we feed them Ritalin or Adderall. And we constantly tell them, explicitly and implicitly through lower grades and lower expectations, that they aren’t smart enough or hardworking enough.

This isn’t a minority of children. I believe students who don’t fit the system are in fact the majority. The factory model was never intended to be the best fit for the greatest number of students. It was, rather, optimized for low cost.

What damage are we doing to these children? What effect does this system have on their self-image? On their expectations of what’s possible for themselves? On the depth of their learning and development? Society ignores this cost because it is largely invisible — and human beings irrationally ignore invisible costs. But the cost of this psychic damage, and the opportunity cost of this underutilization of talent, must be stratospheric.

We’ve all grown up with the factory model of education. It’s come to seem totally normal. It’s not normal at all. It’s just the only way we’ve been able to deliver free widespread K-12 education.

The Teacher’s Burden

Tacitly, we ask teachers to compensate for our education system’s many inadequacies. Do your students need more, or different, content? Make it yourself! What’s that? You were trained as an instructor, not a content creator? Stop complaining. You can find it somewhere! You have students with learning disabilities? Figure out how to reach them! Your students are bored with the state-mandated curriculum? Be more dynamic! Entertain them! You want to help students who are falling behind, or who find the material too easy? Figure out how to personalize it!

Because teachers are the most visible emissaries of the factory model, we irrationally conflate them with its failures. Teachers aren’t “the system.” Teachers are fighting the system, every day, as best they can. What warmth and energy students see in the classroom comes from teachers. Supplemental content, motivation, inspiration and differentiation — it all comes from teachers. Let’s stop blaming them for the system’s shortfalls, and let’s start helping them overcome them.

Changing the System

I can think of many ways to help teachers. They’re undercompensated; let’s pay them more. I know that’s expensive, but it will ultimately more than pay for itself through higher GDP. Studies have found a correlation between higher teacher pay and improved student outcomes. Boosting compensation would attract more qualified people to the field and increase retention.

Students have different needs, tendencies and interests. Let’s give teachers the tools they need to effectively differentiate instruction.

Let’s provide teachers with more training and more time for preparation, mentoring and professional development. Teachers in the U.S. spend about as much time working as instructors in countries like Japan and South Korea. But in the U.S., 53 percent of that time is spent in the classroom, versus 26 percent for instructors in Japan.

Let’s provide career-advancement opportunities to prevent our best teachers from leaving education. A 2012 study from The New Teacher Project found that 20 percent of teachers “who are so successful that they are nearly impossible to replace” leave their school as a result of “neglect and inattention.”

A 2012 MetLife survey reports that the percentage of teachers who report being very satisfied with their jobs dropped 15 points since 2009, from 59 percent to 44 percent, “the lowest level in over 20 years. The percentage of teachers who say they are very or fairly likely to leave the profession has increased by 12 points since 2009, from 17% to 29%.” Not every teacher wants to become an administrator. But many teachers do want a chance to advance within the profession.

Let’s set reasonable expectations, and recognize that teachers can’t fix in a semester societal inequities that have been festering for generations. Let’s substantially reduce the emphasis on high-stakes testing — it’s turning schools into test-prep drilling centers.

Students have different needs, tendencies and interests. Let’s give teachers the tools they need to effectively differentiate instruction. By replacing traditional textbooks with data-driven adaptive learning tools, we can help every student come to class better prepared and give teachers more information about student learning.

Children are innately curious about the world around them. They are learning machines. All they really do, all day long, is learn. It isn’t learning itself they resist; it’s the factory model. It has indeed been the worst system, except all the others that have been tried. We can now do better.

Image is a trademark of Dr. Seuss Enterprises