A group of Internet scholars and legal academics has called on Google to be more transparent about its decision-making process in regards to its implementation of Europe’s so-called ‘Right to be forgotten‘ ruling.

It’s one year since Europe’s top court handed down a legal ruling that requires search engines to process private individuals’ requests for the delisting inaccurate, outdated or irrelevant data returned by a search result for their name.

In that time, Google has processed around 250,000 individual requests, granting delisting to individual requesters in around 40 per cent of cases.

In making these delisting decisions, Google and other search engines are required to weigh up any public interest in knowing the information. It’s more transparency about how Google is making those value judgements that the group is essentially calling for.

They are focusing on Google specifically because it is by far the dominant search engine in Europe (with a circa 90 per cent share of the market), arguing that the information that Google has released thus far has been “anecdotal” — and does not allow outsiders to judge how representative it is.

Writing in an open letter to Google the 80 signatories, who are affiliated with more than 50 universities and institutions around the world, argue that more data is needed to assess how Google is implementing the ruling, and to work towards striking the sought for balance between pro-speech and pro-privacy positions.

They write:

Beyond anecdote, we know very little about what kind and quantity of information is being delisted from search results, what sources are being delisted and on what scale, what kinds of requests fail and in what proportion, and what are Google’s guidelines in striking the balance between individual privacy and freedom of expression interests.

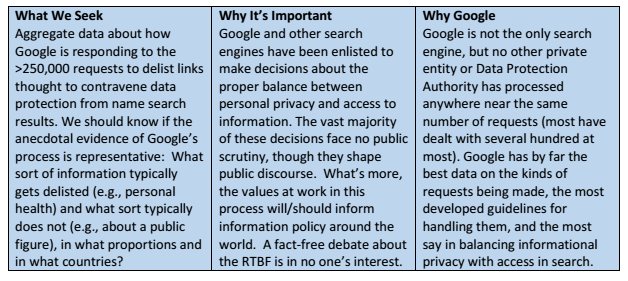

The group summarizes its aims as follows:

Not all signatories of the letter support the rtbf ruling itself, but they are united in their call that Google should stump up more data, writing:

We all believe that implementation of the ruling should be much more transparent for at least two reasons: (1) the public should be able to find out how digital platforms exercise their tremendous power over readily accessible information; and (2) implementation of the ruling will affect the future of the RTBF in Europe and elsewhere, and will more generally inform global efforts to accommodate privacy rights with other interests in data flows.

The group adds:

Peter Fleischer, Google Global Privacy Counsel, reportedly told the 5th European Data Protection Days on May 4 that, “Over time, we are building a rich program of jurisprudence on the [RTBF] decision.” (Bhatti, Bloomberg, May 6). It is a jurisprudence built in the dark. For example, Mr. Fleischer is quoted as saying that the RTBF is “about true and legal content online, not defamation.” This is an interpretation of the scope and meaning of the ruling that deserves much greater elaboration, substantiation, and discussion.

Signatories of the letter include Ian Brown, Professor of Information Security and Privacy at the University of Oxford, Oxford Internet Institute; Lilian Edwards, Professor of Internet Law at the University of Strathclyde; David Erdos, University Lecturer in Law and the Open Society at the University of Cambridge, Faculty of Law; and John Naughton, Professor, Wolfson College at the University of Cambridge.

Another signatory, Peggy Valcke, Professor of Law, Head of Research at KU Leuven – iMinds, is notable as also being a member of Google’s self-styled ‘advisory council‘. Aka the group of academics Google established last year, in response to the rtbf ruling, and which subsequently compiled a report with recommendations for how Mountain View should implement the ruling. Although Google recruited outside experts for that group, the entire process was Google-led — and widely viewed as a sophisticated lobbying effort by the company to apply pressure to a legal ruling it is idealistically and commercially opposed to.

The academics’ letter details 13 data points (listed below in full) which the signatories believe Google should be disclosing — “at a minimum” — in order to help shape the implementation of the rtbf ruling, and “assist in developing reasonable solutions”, as they put it.

Critics of the rtbf have often decried how it requires private companies to make public interest value judgements. The academics’ call to shine more light onto Google’s processes is one answer to this criticism. It also emphasizes the fact that, as it stands, no one except Google is party to enough data to assess and quantify Google’s implementation of the law. Which of course is a farcical situation.

“The ruling effectively enlisted Google into partnership with European states in striking a balance between individual privacy and public discourse interests. The public deserves to know how the governing jurisprudence is developing,” the academics add.

The 13 data points they are calling for Google to release are as follows:

- Categories of RTBF requests/requesters that are excluded or presumptively excluded (e.g., alleged defamation, public figures) and how those categories are defined and assessed.

- Categories of RTBF requests/requesters that are accepted or presumptively accepted (e.g., health information, address or telephone number, intimate information, information older than a certain time) and how those categories are defined and assessed.

- Proportion of requests and successful delistings (in each case by % of requests and URLs) that concern categories including (taken from Google anecdotes): (a) victims of crime or tragedy; (b) health information; (c) address or telephone number; (d) intimate information or photos; (e) people incidentally mentioned in a news story; (f) information about subjects who are minors; (g) accusations for which the claimant was subsequently exonerated, acquitted, or not charged; and (h) political opinions no longer held.

- Breakdown of overall requests (by % of requests and URLs, each according to nation of origin) according to the WP29 Guidelines categories. To the extent that Google uses different categories, such as past crimes or sex life, a breakdown by those categories. Where requests fall into multiple categories, that complexity too can be reflected in the data.

- Reasons for denial of delisting (by % of requests and URLs, each according to nation of origin). Where a decision rests on multiple grounds, that complexity too can be reflected in the data.

- Reasons for grant of delisting (by % of requests and URLs, each according to nation of origin). As above, multi-factored decisions can be reflected in the data.

- Categories of public figures denied delisting (e.g., public official, entertainer), including whether a Wikipedia presence is being used as a general proxy for status as a public figure.

- Source (e.g., professional media, social media, official public records) of material for delisted URLs by % and nation of origin (with top 5-10 sources of URLs in each category).

- Proportion of overall requests and successful delistings (each by % of requests and URLs, and with respect to both, according to nation of origin) concerning information first made available by the requestor (and, if so, (a) whether the information was posted directly by the requestor or by a third party, and (b) whether it is still within the requestor’s control, such as on his/her own Facebook page).

- Proportion of requests (by % of requests and URLs) where the information is targeted to the requester’s own geographic location (e.g., a Spanish newspaper reporting on a Spanish person about a Spanish auction).

- Proportion of searches for delisted pages that actually involve the requester’s name (perhaps in the form of % of delisted URLs that garnered certain threshold percentages of traffic from name searches).

- Proportion of delistings (by % of requests and URLs, each according to nation of origin) for which the original publisher or the relevant data protection authority participated in the decision.

- Specification of (a) types of webmasters that are not notified by default (e.g., malicious porn sites); (b) proportion of delistings (by % of requests and URLs) where the webmaster additionally removes information or applies robots.txt at source; and (c) proportion of delistings (by % of requests and URLs) where the webmaster lodges an objection.

The data that Google does release about rtbf request processing can be found on its Transparency Report — which excludes a handful (22 in all currently) of self-selected examples, such as this one from Belgium:

We’ve reached out to Google for comment on the letter and to ask whether it plans to release the specific data-points requested by the group, and will update this post with any response.

Update: A Google spokesperson provided the following statement to TechCrunch:

We launched a section of our Transparency Report on these removals within 6 months of the ruling because it was important to help the public understand the impact of the ruling. Our Transparency Report is always evolving and it’s helpful to have feedback like this so we know what information the public would find useful. We will consider these ideas, weighing them against the various constraints within which we have to work — operationally and from a data protection standpoint.