Editor’s note: Ben Narasin was an entrepreneur for 25 years before becoming an institutional seed investor. Jeremy Abelson is the founder and portfolio manager of Irving Investors, a growth fund focused on disruptive technologies.

About three years ago we started noticing a sliver of founders who were obsessively focused on valuations start to make short-term decisions in their fundraising that risked meaningful long-term consequences. With the popularity of the “unicorn” label, this trend has gotten worse.

A few months ago a Midas List friend shared a story of dismay with an example in their portfolio that typifies the situation. Their founder had two term sheets to choose from. One was a “clean” term sheet with no preferences beyond the norm and a barely sub-billion-dollar valuation. The other granted the magical, in the founders’ but not investors’ minds, $1 billion valuation in exchange for a set of onerous preferences. The founder chose the latter.

The investor’s fear, which we share, is that the excessive focus on valuation, regardless of terms, can be significantly damaging over time — not just to the founder, but to his team and all the prior shareholders, including seed and venture investors.

“Your valuation, my terms,” has become the response of choice these days from funders to founders demanding outsize valuations, as late-stage investors can achieve their goals by saying yes to one thing and then making up for it with many more.

Part of this is due to the changing nature of funders; many mega-valuation, pref-heavy term sheets come from private equity (PE) shops like hedge and mutual funds accustomed to standardizing on downside protection and guaranteed returns, a very different game than venture. As one friend, who is quite senior at a major PE shop, said, “ I’m fine shooting for 3x return, but I make sure going in that I’m not going to lose money.” This often includes a guaranteed level of return in all cases except absolute failure or close to it.

When we authored our recent piece on the meaningful returns received by PE shops investing in the last private rounds before an IPO, these returns didn’t even factor in the prefs. In reality, PE shops are making even better returns than the already phenomenal ones we detailed through the issuance of additional shares, guaranteed return levels and other downside protections that protective prefs provide. And in the zero-sum game of return, additional return to one party comes out of the return, or through the dilution, of another; specifically founders, employees and prior investors alike.

Let’s look at an example:

Several years ago an entrepreneur raising money in a particularly heated round asked, “How do I get a billion?” He was entirely focused on hitting $1 billion in valuation above all else. He didn’t get to his billion target in that round, though he got close, but he did in a later round, at a significant cost. The cost was paid when the company went public.

The cost of the valuation was a guaranteed return on the investment made: at least 2x on IPO. Beyond being onerous, as the IPO proved, it set a precedent and pattern. A later investor got a guarantee of 1.5x and the one thereafter a more traditional 1x; although a 1x guarantee on IPO is very different from a traditional 1x liquidation preference, which only kicks in on the sale of the company or a similar event.

When the company IPOed it did so below the $1 billion valuation, and the preferences kicked in. In order to make good on the guarantees the company had to issue additional post- IPO stock, which diluted all the non-pref-enriched shareholders by almost 15 percent.

The company’s shares also traded down significantly on opening day, chalking up an unwanted record; the biggest first day dip in IPO price of any U.S. company that year.

More recently, when Box priced its IPO at $14 a share, below its last private round at $20, it triggered the preferences to their last private investors, Coatue and TPG, including “profit protection.” According to Box’s S-1, every share of Series F stock converted into shares of common stock equal to $20 divided by the lesser of 90 percent of the price per share of common stock, or $20, meaning Series F investors were guaranteed at least a 10 percent discount to the IPO price. If not the balance was made up in additional stock grants.

So if Box priced at $22.22 or above, the Series F shareholders wouldn’t receive any additional shares from their preference for the shares they paid $20 thereby locking in a 10 percent profit plus all upside above $22.22. But Box priced at $14, triggering the preference and ever Series F share converted into 1.587 shares of public common, versus the one-to-one conversion they would have achieved at a $22.22 price, and further diluted the shareholder base.

Box’s most recent 10K reports a share count of 119.8 million, but if the series F had not converted the number would have been 115.4 million, meaning the company issued an additional 4.4 million shares as a make good on top of the original 7.5 million shares originally converted. Without a conversion preference, the Series F holders would have converted to 6.5 percent of the shares, with the preference that increased, post IPO, to 10 percent (54 percent accretion for Series F PE shareholders) and lowered the remaining shareholders ownership from 93.5 percent to 90 percent.

To make this that much more frustrating to the founders and investors before the final investor, Box’s shares actually traded as high as $24.73 on opening day, well above the $22.22 protection price, but since ratchets are triggered by IPO pricing the last private round investors received their additional shares regardless.

Prior private preferred rounds (PPR) are not uncommon in IPOs, but they do appear to be more common in TMT (Technology Media & Telecommunications) IPOs, and are even more pronounced in TMT IPO down rounds.

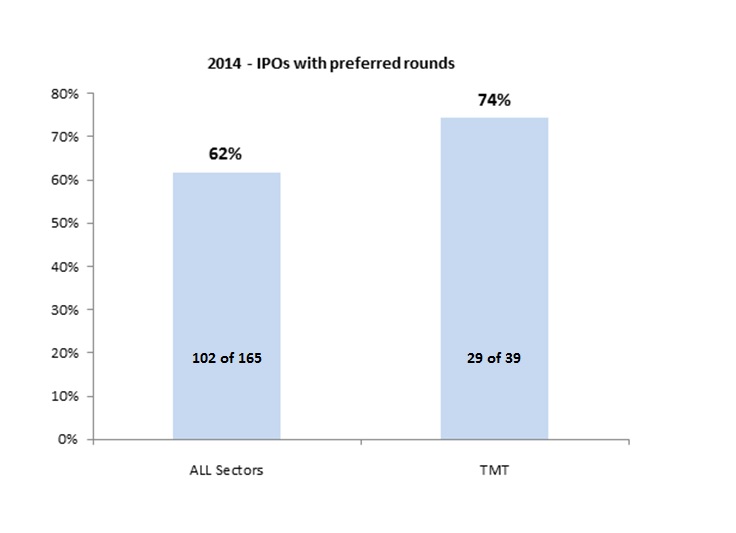

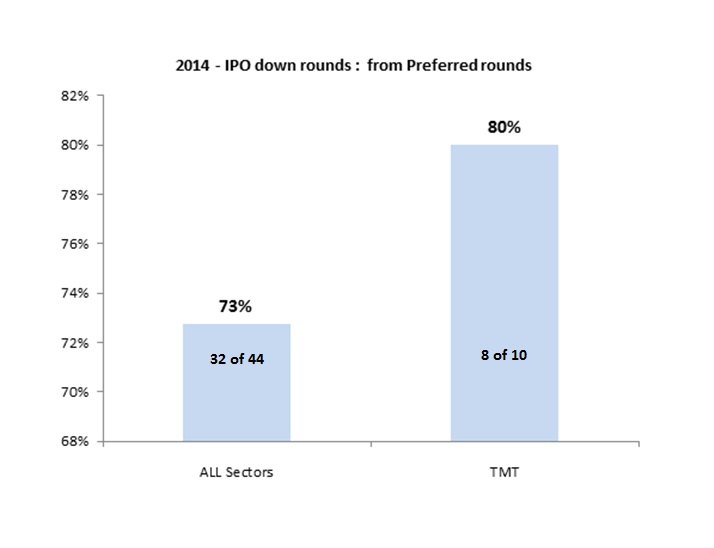

Our analysis of 2014 IPOs showed that while 63 percent of all IPOs had PPRs, 74 percent of TMT IPOs had PPRs. In down rounds 73 percent of all IPOs, and 80 percent of TMT IPOs had PPRs. Correlation does not demonstrate causation of course, but this raises the issue of how logical those funding decisions, as relates to terms, were in respect to the position of the company and its fair value versus a desired valuation at the time.

In some cases, the preferences are a result of the golden rule, the man with the gold makes the rules, and they are the cost of raising a difficult round. But in many of the recent cases, where clean term sheets were available at slightly lower valuations, they seem to be merely about a specific valuation and what it means to a founder’s pride or publicity.

Founders point to being “dilution sensitive” as a primary reason for their valuation demands, but we don’t think they are focusing on the all-in potential levels of dilution enough, particularly when pride plays in the picture. Is being a “unicorn” worth taking an entire extra round of dilution later? If a late-stage investor demanded 30 or 40 percent upfront for their investment, would a rational founder consider it? Yet that was the end result in the case of our earlier example.

So, for founders and funders alike, it’s not just about the valuation, it’s about the whole deal. Focusing excessively on valuation risks losing focus, and negotiating leverage, in the rest of the deal terms. Valuation is a part of the picture, but dilution, all-in dilution, is another very important part. We often say the only “valuation” that matters is the last one, in that valuation and ownership at liquidity is the ultimate measure for any shareholder. It’s a long journey to get there, so pay attention along the way.