Editor’s note: Scott Nolan is a partner at Founders Fund where he focuses on investments in technology- and engineering-driven companies across all sectors. Prior to Founders Fund, Scott was an early engineer at SpaceX, founded a consumer Internet company and worked in private equity.

“The sky is falling!” VCs first sounded the alarm in September, claiming that startup burn rates had reached dangerous heights and companies must be wary lest they “vaporize.” Six months later amid the frenzy of SXSW, many of the same voices raised concerns over valuations and cried bubble. Sensationalism makes for great press, and “burn rate” and “bubble” are once again front and center in the tech world’s hive mind.

Too bad burn rate doesn’t matter.

More specifically, burn rate (net cash outflow per month) is a vanity metric. Just as top-line revenue doesn’t tell you much about the health of a DJIA blue-chip, burn rate says very little about whether a startup is on track. Only by evaluating a company’s use of cash and long-term strategy can high burn be diagnosed as good or bad. In many cases, the low burn ideal is actually dangerous.

At Founders Fund we avoid investing in companies unless they are consuming cash. We’re here to invest when doing so will bring about positive progress faster, which often manifests as the conversion of cash into assets and increased burn. Cash-flow-positive businesses are usually past this inflection point, or simply don’t have enough ideas about what valuable things to do with more money.

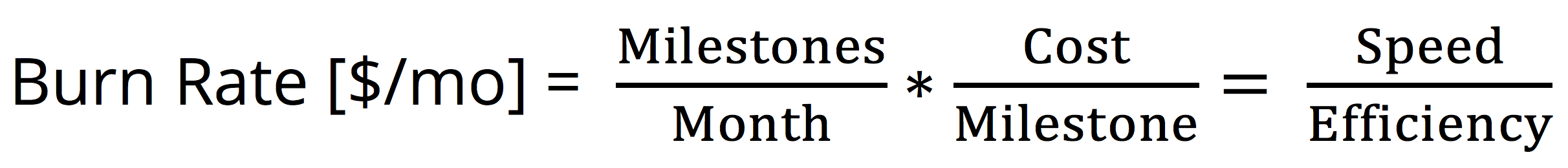

So can anything productive be said about burn rate? Basic algebra offers some insight:

This reveals a simple truth: two companies with identical burn rates can be worlds apart, based on what they’re actually doing with the money. By breaking down burn rate into “speed of execution” and “efficiency of execution,” we can focus on what matters to startups: achieving specific goals corresponding to a chosen strategy.

Beneath the surface

When it comes to speed of execution – or “milestone rate” – faster is almost always better. An enterprise software company’s next milestone might be winning a contract up for bid, while a breakthrough tech company might have a specific engineering achievement in its crosshairs. The more rapidly progress is made, the less can change externally while the strategy is being executed and the greater the chance of success.

Efficiency of execution offers an orthogonal lens — whether the gain of achieving a milestone is worth the cost. For the enterprise software company, did the cost of closing the contract exceed its value to the company, and if so by what multiple? At the deep tech company, to what degree was the engineering breakthrough worth the R&D expense? For any given milestone and execution speed, lower cost is better.

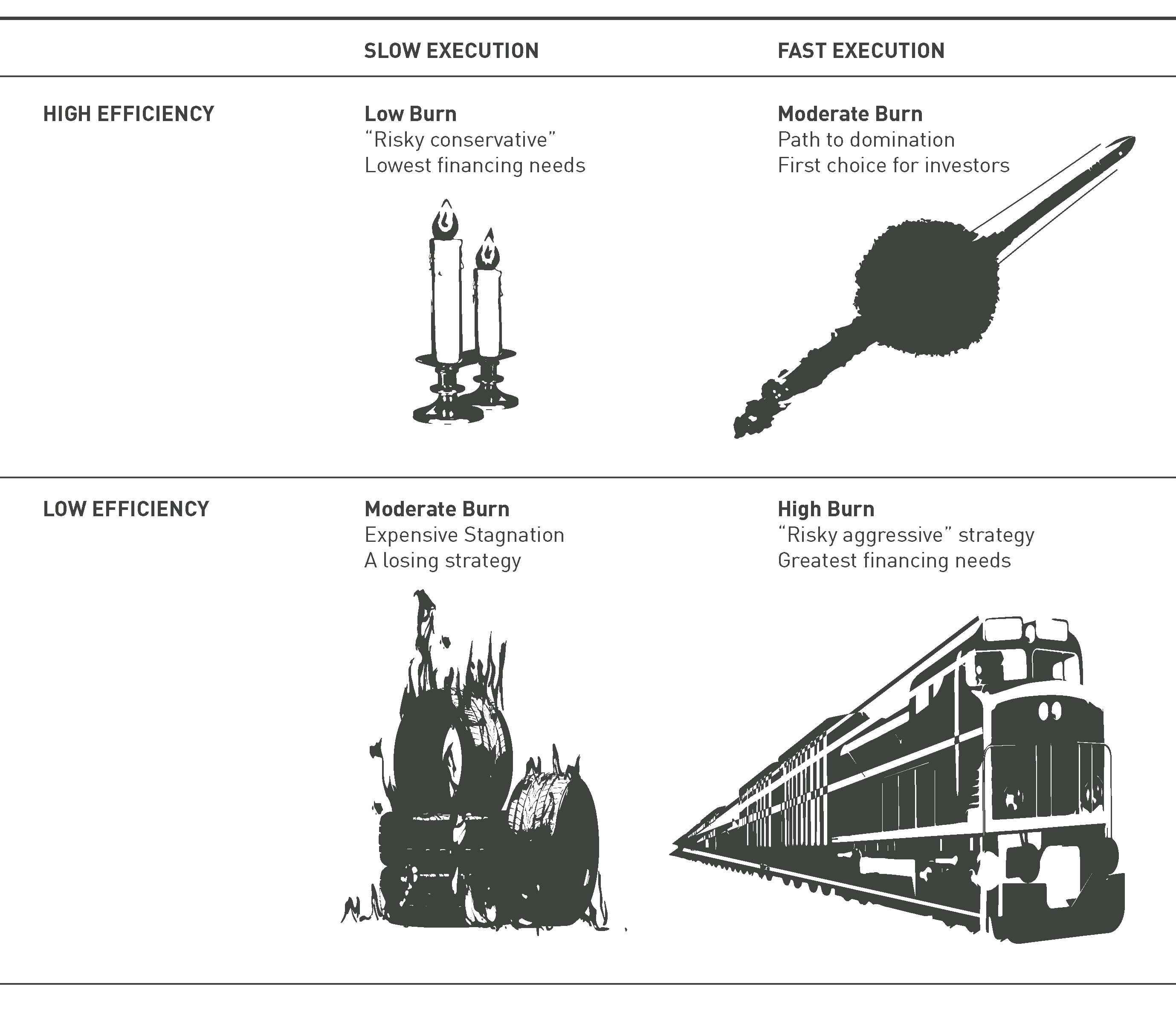

All things equal, these two metrics yield a framework of four relative categories:

Looking beyond burn rate, we ask ourselves: where are the worst companies located on this chart? Obviously, the truly doomed companies are in the lower left, a place of only moderate burn. These companies are moving slowly and they’re inefficient — the worst of both worlds.

But just like these badly executing companies in the lower-left quadrant, the exemplar “fast-efficient” companies in the upper right also have “moderate” burn rates. This alone is reason to believe that burn rate is not only the wrong framework, but isn’t even correlated to how well a company is executing or its long-term potential.

Searching for the highest burn companies, we find them in the bottom right. If burn rate truly mattered most, we would conclude that companies in this “fast-inefficient” quadrant are also in the worst shape. But while low efficiency isn’t optimal, at least these companies are executing quickly. When spend is NPV-positive, action is better than stagnation. Many “unicorns” understand this, wisely living here during their early years while building deep moats around their business, even at efficiency’s expense.

In many cases, we need higher burn today for a better tomorrow.

Meanwhile, their low burn antipodes in the upper-left quadrant are much worse off. Companies here are like doomsday preppers hunkering down in the final moments before Y2K. Even when markets turn cold and financing scarce, investor “flight to quality” will have a bias toward companies with the richest track record: those on the right-hand side. The most valuable, important companies of the decades ahead are building the future today, executing quickly and burning money in the process. The best investors understand this and invest accordingly.

In fact, not only is the conventional burn rate wisdom wrong, it’s also misleading. For companies in the upper-right quadrant with great businesses and a path to profitability, striving to increase burn rate — in order to increase milestone rate — is usually best. To suggest that a company developing something the world actually needs — e.g. a cure for cancer or unlimited clean energy — should slow down execution is an attack on progress.

Predicting the future

No one will deny that some of today’s unicorns might be tomorrow’s failures. Not every company in a competitive winner-take-all market can win, and even unicorns compete. And yes, there are probably unicorns today deploying capital in NPV-negative ways or building bloated overhead. If the financing world suddenly became less optimistic, these “fast-inefficient” companies may need to adapt or die.

But to predict who will thrive requires much deeper analysis than simply quoting burn rate, or even diagnosing speed and efficiency. Each sector has its own keys to success, and each company its own strategy. While financing is an important consideration, it’s only part of the equation. Thinking from first principles is how true insight is earned, and as such there are few easy shortcuts.

The tech community needs to do better than sound bites and broad generalizations — sometimes self-serving — on which the burn debate has survived. As long as we are striving to build a better future that is not yet obvious, we need to avoid rhetoric and instead be diligent in our thinking — not just by considering the financing environment, but also by looking beyond the surface of each company and acknowledging that burn is not always bad. In many cases, we need higher burn today for a better tomorrow.

For better or worse, this will require critical thinking and real effort. It’s time to smile and roll up our sleeves. A better future isn’t going to build itself.