Facebook’s move to turn Messenger into a platform for third parties has been one of the company’s most important decisions to date. Mobile messaging is a pivotal trend that will shape the way billions of people consume the Internet.

It has the potential to overhaul the dynamics of digital distribution, but Facebook’s platform must go beyond hosting apps and become a mobile web experience if it is to have a shot at mainstream success.Smartphones have long been heralded as the great leveler that will bring Internet access to billions of new users for the first time. With that shift now starting to take place — among both younger and older demographics in Western markets, and beyond the more affluent consumers in emerging markets — mobile is now radically changing the way that the Internet is used. Today, it is inherently a mobile-first model, to the point that many people don’t consider the apps on their phone — and primarily Facebook — to be part of the Internet.

With that backdrop, the ‘platformization’ of Facebook is designed with the aim of owning the smartphone Internet experience in a way that is unprecedented so far in the West.

Disruption

New in the West it may be, but there are already examples that Facebook can follow for its blueprint. Messaging apps in Asia have been platforms for games, camera apps, multimedia, and more for a couple of years now. The most striking example is in China, where WeChat, an app from billion-dollar Internet firm Tencent, has grown into the primary mobile Internet portal.

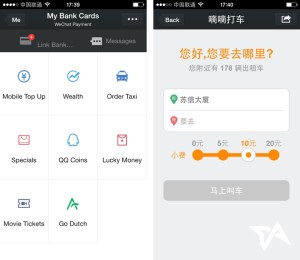

Shopping inside Weixin — image via Technode

Weixin, the Chinese-version of WeChat, is basically the mobile Internet for China.

That’s to say that, beyond text or video chats with friends, you can do all manner of things: book a taxi; read news; shop at e-commerce stores; order take-out; and pay bills.

The Weixin platform is open for any company to build on. They can, for example, develop their own optimized Weixin sites, which is basically a website optimized for the messaging service with some native functionality.

In some cases, that’s all you need for distribution in China. Food on-demand startup Call A Chicken raised $1.6 million off the back of its Weixin app. It doesn’t even have a website; it doesn’t need one.

Ordering a taxi via Weixin — image via Tech In Asia

So Weixin is akin to a consumer-friendly skin for the Internet. It is literally a gateway to the web, which makes it hugely powerful and influential.

That is the level of disruption we are talking about here.

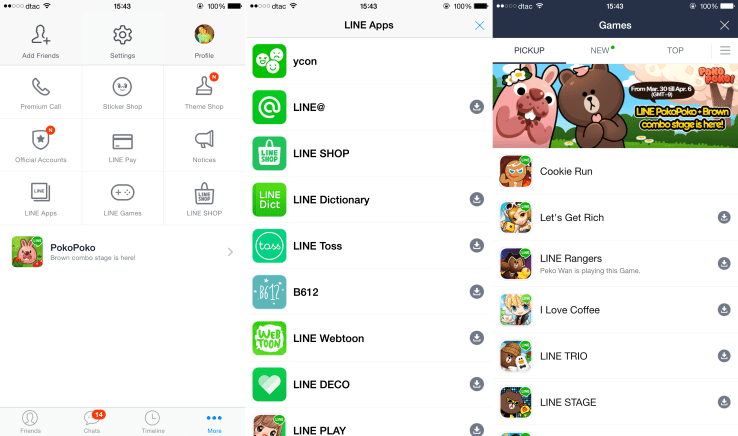

Though it is undoubtedly inspired by Weixin — it’s hard not to be — Facebook is taking a different approach. Initially, at least. It is using the app platform route pioneered most prominently by Japanese chat app Line, which plugs a selection of apps from invited partners into its service. It isn’t open to all, and you are taken to a standalone app outside of Messenger when using these partner apps.

Line, which has over 500 million registered users and is predominantly focused on gaming, has more than 50 apps that let you play social games with friends, take quirky photos, and use other utility apps that are optimized for its chat app and are tied to your social graph there. Kakao Talk, a service in Korea, has a similar system — that’s helped it turn in profit and dominate the iOS and Google Play store charts.

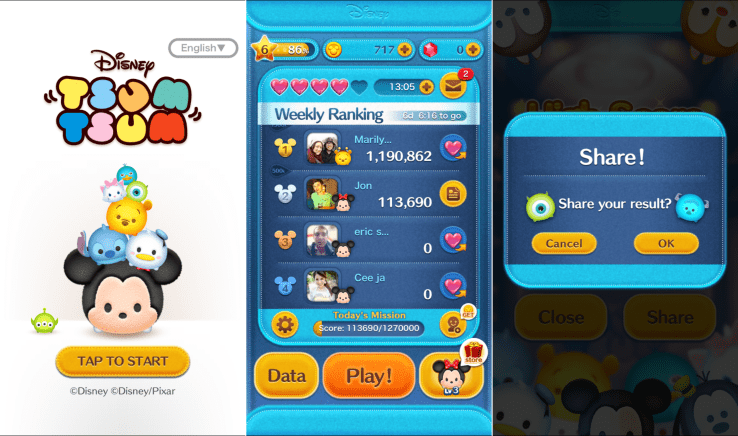

Unlike Weixin, Line is a closed network. App makers are invited into its ecosystem. Most are games companies that re-skin their titles for Line (using its SDK). These games are published under Line’s name, using what appears to be a revenue share deal. They are popular, too. The Line games platform is approaching 400 million cumulative downloads, while games accounted for over half of Line’s $200 million revenue in Q4 2014.

Disney TsumTsum is one of Line’s most popular games

Line is beginning to move into new content, having launched a fund to invest in online-to-offline services, because its financial success is so dependent on games. Parent company Naver missed its most recent financial target because Line’s top games didn’t perform as expected, but, as an app ecosystem, broadening the scope is harder for Line than it is for Tencent/Weixin, which can integrate new services with relative ease — its latest push has been restaurant listings and location-based services.

Cracking the U.S.

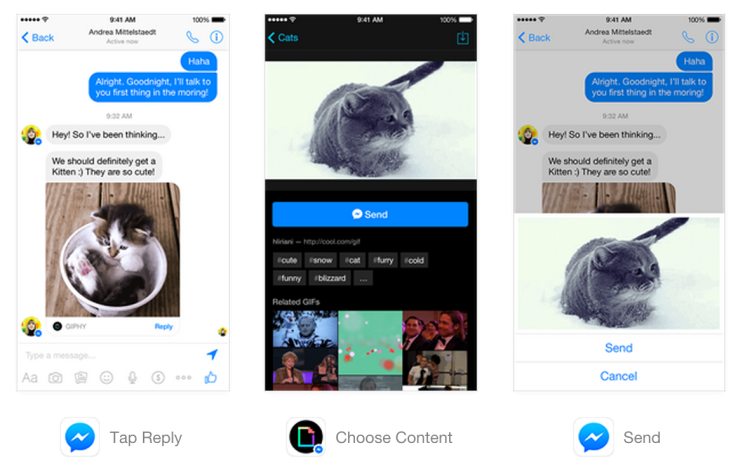

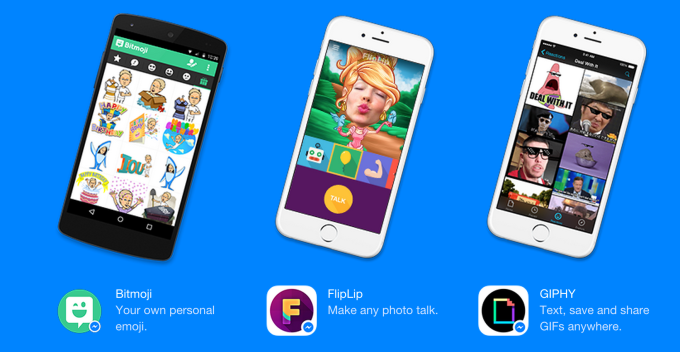

Facebook isn’t focused on games for Messenger, at this point, although it has run tests highlighting them inside the app. Instead it seems to be leaning on media via the integration of third-party apps like GIF portal Giphy, news content like ESPN and its own selfie apps. While it has launched a potentially useful feature that lets consumers and business converse via Messenger (it’s remarkably similar to what mobile social network Path offers) it’s interesting that there’s no immediate integration with Uber (Google is an investor, and Uber allows one-click taxi calling in third-party apps) or on-demand apps like Postmates or music services, which are inherently social in nature.

It could be that these services will be integrated with Messenger in the future. That is necessary if Messenger is to become a useful internal portal like WeChat. However one reason for this initial approach could be that Facebook is first focused on cracking the U.S., which is the second-largest smartphone market behind China and, crucially, a place where no single chat app has won out.

Its Messenger for business platform, the aforementioned replacement for email, requires local customer service teams and actual resources to be effective, so that will entail gradual rollouts worldwide as opposed to automated integration that can roll out fast. But beyond that, there are important cultural differences in mobile consumption that make creating a powerful messaging platform in the U.S. more challenging than in Asia.

Primarily that is because Messenger and other rival apps don’t provide features or a use case that consumers are immediately compelled by. In Asia, free text messaging and Internet-powered voice calls are attractive because many consumers are on pre-pay mobile deals — that accounts for over 90 percent of mobile users in India, for example.

For those people, text messages are not free (whether sold as a bundled deal or individual pricing) while equally, in many countries, calling someone who is on a different mobile network is charged at a higher rate than calls made on the same network. (Hence dual SIM devices are popular because it is cheaper to use different SIMs to call different people.)

In these cases, the free communications of Line, WeChat, WhatsApp and even Messenger have immediate value that hooks a user in and keeps them. When you sign up for Line in Thailand, for example, you’ll find most of your phone book contacts are there already, which increases the chances that you’ll become a heavy user. With that sticky user experience as its foundation, chat apps in Asia have moved into offer-related services and content like taxis, shopping, payments and more.

But the high use of iMessage and the near low (free) cost of SMS in the U.S. makes it trickier to make such a compelling use case. The same is true for Twitter DMs, Facebook Messenger and other other social networks: If you have used other services to communicate with friends for free for years, why switch now?

It’s early days, but it looks like Facebook is tapping the ‘SMS+’ route with Messenger. That’s to say that it is offering features that you can’t find in regular SMS, the idea being that the appeal of sending GIFs or goofy selfies, is a trigger that will make people switch their usual channel for conversations to Messenger. Media companies like ESPN are also early partners to give another reason beyond communication to check Messenger daily.

The U.S. chat app space is nascent so it’s not known if this will work. Snapchat offered a very differentiated service, initially at least, with disappearing photos. That worked among a young demographic, and Snapchat has matured as a product — and also turning into a platform — to offer more public photo sharing and add a media facet to its business with the launch of its Discover service. Initial reports suggest that Discover is sending plenty of business to its early media partners, but it’s impossible to gauge whether it is increasing engagement among loyal users and broadening Snapchat’s audience beyond early users because the company doesn’t provide user numbers.

From what I’ve witnessed in Asia, media and photo integrations are fun, but messaging apps get interesting when they offer more compelling, everyday services. I was pretty blown away during a recent trip to Beijing when my Airbnb host booked me a taxi in a few clicks from inside Weixin; almost in an instant, it was done and she went back to chatting with her friends. That’s a compelling use case because it lowers the friction point for using a range of services from your phone.

In another example, friends of mine in Thailand often moan about Line. Yet, despite their grumblings about the app, they are daily users because it is bigger than Facebook here and has become a must-have for anyone in the country. With on-demand groceries planned, a TV platform with exclusive content, and other services like taxi booking starting out in Japan, Line might as well be pre-bundled on devices; it’s arguably more important than a phone’s native calling app.

Line has an array of connected apps and games

Competition

This is the route Facebook is taking, but in order to become a daily must-have app — especially in the U.S. — it needs to be far more compelling than it initially is.

If Facebook needs more local, Western examples beyond Snapchat — which it famously tried to buy for $3 billion — then Canada-based Kik is one to watch.

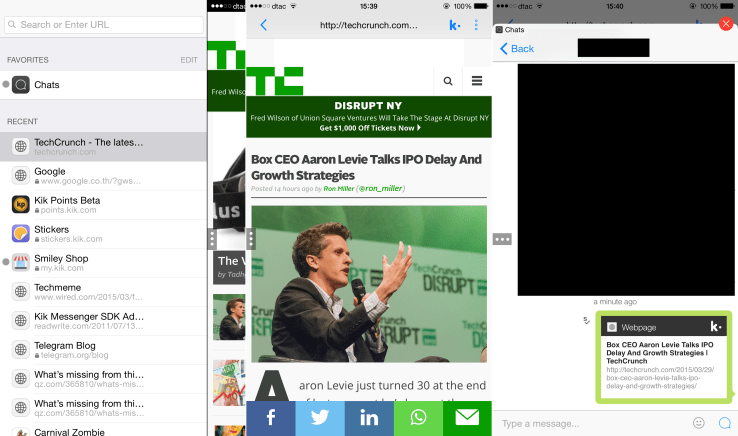

It’s a veteran in this space, having launched an SDK that let mobile apps plug into its ‘platform’ way back in 2011. Timing is so often about consumer behavior — just ask the video sharing companies that hit the market before Meerkat and Periscope took off — and Kik’s platform failed because it was too early. That said, the company learned lessons and pivoted to a WeChat-style web-based platform last year, claiming that the change would reduce friction when using third-party services and provide an easier experience all round.

If I send you a GIF on Messenger and you like the content and want to do the same yourself, you’ll have to download that third-party app. You hit the link inside Messenger and are directed to the App Store or Google Play to get the app. A minute or two after downloading it, you sign in to Giphy For Messenger with your Facebook creds and return to Messenger to sync it up and start sharing your own creations.

There’s a lot of waiting around and moving parts in that process. To make things easier, Kik put an HTML5-based browser inside its messaging app so that I can visit the Giphy website, find the GIF I want and quickly ‘Kik’ it over to our chat window within seconds. No app install is needed, and I can share content from any website that way — even this article, for example. Site owners can add a snippet of code to optimize their website for Kik sharing, and add native app features like push notifications.

Sharing a link in Kik is easy

In taking a web-centric approach, rather than the app-based route of Facebook Messenger, Kik opened itself up to any website or service. That brings the potential for many opportunities beyond just GIF sharing, because sharing any kind of web content on Kik requires minimal effort from consumers, and is easy for developers.

Things will get more interesting when Kik adds a payment service this year. In theory, you’ll be able to shop on Amazon inside Kik — and share items with friends — even without Amazon even adding support. The process could be made slicker if Amazon chooses to support Kik’s platform.

With 200 million registered users, Kik is nothing like as popular as Facebook Messenger (600 million active users) worldwide, but it does claim to be on par with its competition in the U.S. Users in the U.S., it claimed, spend 35 minutes per day inside its app. That’s a number only bettered by Facebook: which a report estimated sees 37 minutes per session on average.

It is primarily popular with a younger audience thanks to features like usernames — which avoids the need to share your phone number — and its compatibility with the iPod Touch a couple of years ago. But Kik CEO and co-founder Ted Livingston believes that the next generation of young people are naturally drawn to chat and will want to do a lot more inside messaging apps.

“Young consumers in the West are like all consumers in the East. They haven’t yet decided where to bank, where to shop, or what games to play. But they all chat,” Livingston told TechCrunch recently.

The challenge for Facebook is that it doesn’t own this demographic in the U.S.. In fact, Facebook is so ubiquitous that it is difficult to appeal to everyone. Clearly it needs to offer something more than just media to stand out, and useful integrations seem like a no-brainer.

The prospects of success for Messenger are pretty rosier overseas, in spite of chat apps in Asia. Forget what you might have read about Facebook’s impending demise, it is still huge in places like Africa and Asia, even in some countries where chat apps are well established. Chat apps are often for communicating with your close circle, but Facebook covers a wider audience — for example, I quickly found that it is used instead of LinkedIn across most of Asia.

There are plenty of markets in Asia where no clear messaging app has won out. With the right integrations, Facebook Messenger could gobble up market share in those places, even though WhatsApp will remain a platform-free messaging app. But, while the initial signs are promising, Facebook has much to do to develop Messenger. It would be wise to follow the open, intranet-like Weixin mode.