Nigeria enjoyed some good press for the better part of last year. Its impressive economic growth, averaging 6 percent annually for the past ten years, crowned it Africa’s top economy.

The World Health Organization declared the country Ebola-free, after the government’s swift and impressive public health response. While the world lauded Nigeria’s noteworthy successes and worried about Boko Haram’s kidnappings and murders, most media ignored a troubling and growing kidnapping-for-profit racket.

The Economist magazine estimates that kidnappers in Yemen, North Africa and Somalia took in up to $125m over the last six years. The Somali pirates, made infamous by the Tom Hanks movie Captain Phillips, have raked in some $400m in ransoms from kidnapping since 2008. But they are small-time compared to Nigeria’s kidnappers. We have spent several months researching kidnappings in Nigeria and have interviewed dozens of participants in this industry. Nigeria’s kidnappers have harvested an estimated $600m for the same period.

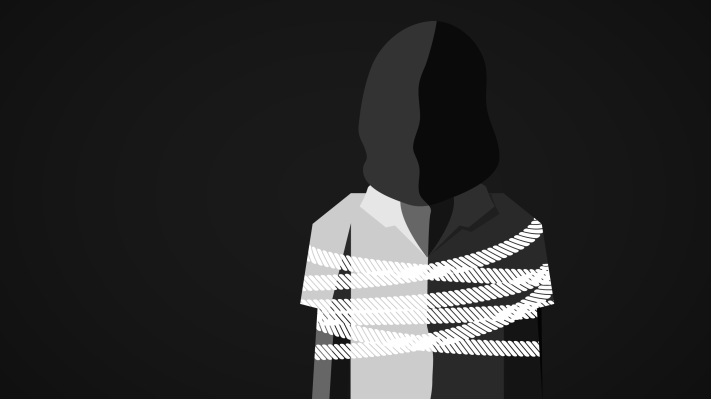

They said somebody needed to pay for my life. They asked for 20 million Naira and then they would cock the gun and say they will shoot me if they didn’t get the money. I thought my life was over. They then give me the phone to talk to a family member and to tell them to bring the money. Samuel

We interviewed one victim, the owner of a hotel in Aba named Samuel, who spoke of watching the gang search all his hotel rooms, seize people’s cell phones, and then finally driving him deep into the bush, tying him to a tree and blindfolding him. “They said somebody needed to pay for my life. They asked for 20 million Naira and then they would cock the gun and say they will shoot me if they didn’t get the money. I thought my life was over. They then give me the phone to talk to a family member and to tell them to bring the money.”

We interviewed many such victims. It is tempting to view kidnapping in Nigeria as one terrifying extension of the Boko Haram ‘kidnapping-as-terror’ model. But that doesn’t fit the situation on the ground. We interviewed 21 people in Nigeria either involved in or victims of kidnapping, including those who worked in government, police, private security and legal services, and found a much more organized ‘kidnapping-as-business’ model.

The kidnapping business has evolved by trial and success into an intricate web of key partnerships and personnel – including law enforcement. Some police officers play both sides of the coin, and can be dangerous “friends” for the kidnappers — even after bribes are collected, police may return repeatedly, demanding additional bribes from the assailants.

The kidnapping business has evolved by trial and success into an intricate web of key partnerships and personnel – including law enforcement.

In Samuel’s case, the ransom wasn’t paid fast enough, which led to a grueling ordeal. Two days after he was taken, the kidnappers reduced the ransom to 10 million Naira. Later that evening, they reduced it to 5 million, then 1 million and started beating Samuel, saying they had to have it. The two parties finally settled on 500,000 Naira (about $3,500), but when Samuel’s uncle dropped the money off, it was only 200,000. This time, he was tortured. “They lit rubber and allowed it to burn on my leg. They tied a plastic bag around my feet and lit it on fire. My feet were burning.”

Finally, three days after the kidnapping, Samuel’s uncle scraped together the remaining 300,000 Naira, dropped it off and the hotel owner was released. Samuel’s kidnappers were never caught. But Samuel was one of the lucky ones: at least 10% of victims die during the kidnapping process, according to our sources.

Two primary reasons kidnapping thrives are, first, people are desperate to make a living. The excitement around the potential created by a large, young, and growing workforce comes alongside the very real concern about the prospect of rising crime from unemployed and desperate youth looking for a quick payday.

Second, law enforcement and the judiciary are often compromised. This factor is key, because it undermines the very channels needed to arrest the process at any step of the way. Our sources estimate that out of every 100 kidnappings, 20 kidnappers are caught, two are brought to trial, and only one is convicted within five years of arrest. If more kidnappers were caught and brought to justice, this would become less appealing as an occupation.

If Nigeria wants to convince the world she’s open for business and can lead the so-called MINT economies (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, Turkey), this kidnapping industry has to stop. There are at least three ways Nigeria can begin addressing systematic kidnapping-as-business. The most important and potentially most difficult involves rooting out the localized culture of corruption within law enforcement and legal systems that make it nearly impossible to bring perpetrators to justice. Nigeria should consider:

1. Paying law enforcement a living wage.

2. Hiring undercover anti-corruption units within the police and judiciary.

3. Empowering local champions and change agents—leaders who build effective institutions and enforce the rule of law.

Nigeria is paying a heavy price for its culture of kidnapping — in human lives, in collective fear and intimidation, and in economic costs that in some places reaches 6% of the GDP.

To support Nigeria, the rest of the world should consider:

1. Putting the issue of kidnapping-for-business under the media spotlight: Nigeria’s leadership cares a lot about how it is perceived globally.

2. Sharing success stories of locally empowered citizens making a difference. Some ordinary people are doing extraordinary things in the face of corruption and power excesses. The website I Paid a Bribe , which has an explicit goal of fighting corruption, is one such example.

There is no silver bullet. However, we see signs of hope, be it a strong state governor, a capable and just security agent, the collective protest against the government’s non-response to the many school girls kidnapped in Chibok, or last year’s successful actions by public leaders and hospitals against the spread of Ebola. It is from these beginnings that Nigeria can nurture incremental positive change.

As they say in Nigeria, “Change am, but small, small” (Change it, but slowly).

Editor’s Note: Yaw Boateng is a business consultant based in Lagos, Nigeria, who has spent the last decade working across Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Ghana, Sierra Leone and the United Arab Emirates advising companies on doing business in Nigeria. He has been published in The Economist and widely quoted by the Financial Times. Richard Slota is a playwright and poet based in San Francisco, California, who visits Nigeria frequently.

This paper from Boateng and Slota is the culmination of research into the methods and economics of kidnapping. Yaw Boateng appeared on the Planet Money podcast to talk about what he learned while researching how to keep his girlfriend safe from kidnappers in Nigeria – and how to deal with them if she is kidnapped. This white paper is the result of his research.