If you were looking for love in Austin this weekend, you might have run into Ava — a chatbot on Tinder created to promote the South by Southwest premiere of a new science fiction film called Ex Machina.

Regardless of what you think about the campaign (I didn’t have a problem with it, but then I’ve always found Tinder chats to be awkward and slightly surreal), it certainly fit with the film’s plot. In Ex Machina, Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson), an employee at a large, Google-esque company, wins a contest and gets to spend a week with the company’s reclusive founder Nathan (Oscar Isaac).

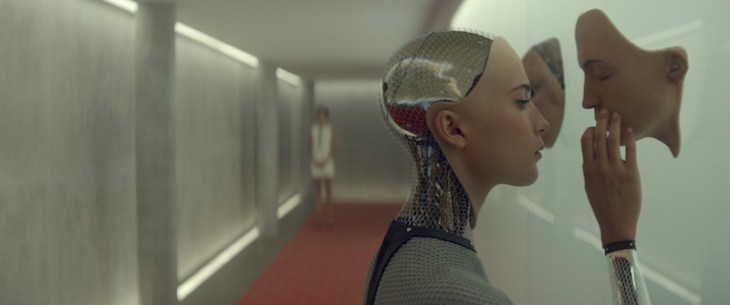

Turns out, however, that Nathan has something specific in mind — he wants Caleb to interview Ava (Alicia Vikander), an artificial intelligence housed in a female, humanoid body, and determine whether or not she’s achieved true consciousness. Of course, there’s more going on than Nathan will admit, and tense, sexually fraught hijinks ensue.

Ex Machina is also the directorial debut of Alex Garland, who previously wrote The Beach (the novel) and 28 Days Later (the film). Garland was in New York City last week to promote the movie, and we spent a few minutes talking about the new film’s big ideas.

Garland was quick to say the movie is, in many ways, “a fantasy.” In other words, even though he believes it’s “quite likely” that strong artificial intelligences will exist at some point, the movie asks you to “just take a leap of faith” and accept it, and also accept that we’ll be able to build robots that can replicate the nuances of human expression.

Ultimately, it sounds like Garland spent less time worried about the technical questions and more time focused on the philosophical issues, which he described as “conversations about strong AIs, conversations about human consciousness, the hard problems of consciousness.” The idea for the film first came to him while he was working on another movie, Dredd, and he read Embodiment and the Inner Life, a book by Murray Shanahan, which addressed many of these topics.

To be honest, Garland’s summary of the book and its attempts to refute metaphysical skepticism about the development of strong AI (I think?) went a little above my head, but I did catch that he asked Shanahan (a professor of cognitive robotics at Imperial College London) for feedback on the script. In fact, Garland said he consulted with a number of experts for this film, partly because of his experience with a previous movie, Sunshine — probably my favorite thing he’s written, and a film I’ve seen countless times. But Garland said some parts dissatisfied him because they weren’t scientifically vetted and ended up being “just sort of gibberish.” And he didn’t want that kind of gibberish to sneak into Ex Machina.

The movie will be released in the United States on April 10 — about a month after Chappie, and a month before the release of Avengers: Age of Ultron. So … why are all these AI-centric movies coming out at once? Garland has a theory.

“It’s not because research into AI has reached a critical mass,” he said. “I’m almost 100 percent sure it hasn’t — we’re not just about to create conscious machines. It’s actually got more to do with search engines. There’s a sense that we’re giving up a lot of information to tech companies and machines.”

As a result, Garland said, “We’re reaching a point where we feel that we don’t understand machines and how they work, yet they know quite a lot about us.” In their very different ways, these movies reflect that “unease.” (And that, by the way, also explains why Garland made the film’s morally ambiguous inventor the creator of a search engine as well.)

But all of this talk dances around what’s probably Ex Machina‘s central question: How do you actually identify human-level consciousness? This is the issue that Nathan and Caleb return to again and again as they run their own variant of the Turing test — which, after all, is more about the appearance of consciousness than consciousness itself.

Ultimately, Garland does propose a possible answer … but one that I can’t share without spoiling the film. So let me just say that I think that it’s a satisfying answer, and it comes at the end of a terrific movie that you should absolutely see.

And seriously, if you don’t want to be spoiled, stop reading now.

Okay, well, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

If you’ve managed to catch a screening already, or you don’t mind getting hints about the ending, here’s Garland’s take:

The film presents an answer from my point of view. After all is said and done, and one guy’s got stabbed, another guy’s trapped, and this robot may or may not have an agenda, she goes up a lift, walks across the room, looks back over her shoulder, and she smiles. There’s nobody else in the room to trick — from my point of view, if you believed you were unobserved and you were smiling to yourself, that seems like as close as you come to your true self.