In a report published today, the U.K. parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee has called for a new single act of Parliament to govern how domestic spy agencies operate with the aim of improving transparency and public trust. It dubs its report “an important first step towards greater transparency”.

The 149-page report is the cumulation of a year long inquiry by the committee, set against the backdrop of ongoing revelations derived from documents leaked by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden (some of which have specifically pertained to the U.K. GCHQ spy agency), with the aim of examining the operations of the UK intelligence and security agencies — looking specifically at (in the committee’s own words):

- the range of intrusive capabilities currently available to the Agencies;

- how those capabilities are used, and the scale of that use;

- the extent to which the capabilities intrude on privacy; and

- most importantly, the legal authorities and safeguards that regulate their use

The committee claims to have found no evidence of U.K. government agencies seeking to circumvent the law, but does flag up what it says is a “lack of clarity in the existing legislation” — pointing to this as having “fuelled suspicion” about agencies’ activities.

“Minor reforms and improvements around the edges of the existing legislation are not sufficient in the long term. Therefore, rather than simply reforming RIPA [Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act], as some have suggested, we consider that the entire legal framework, as it applies to the intelligence Agencies, needs replacing,” the committee writes.

“The purposes, functions, capabilities and obligations of the Agencies should be clearly

set out in a new single Act of Parliament. This should also include the privacy constraints, transparency requirements, targeting criteria, sharing arrangements and other safeguards that apply to the use of their capabilities.”

“These changes are overdue,” it adds. “There is a legitimate public expectation of openness and transparency in today’s society. Therefore, while the Agencies must operate in secret if they are to be able to protect us – and we cannot expect them to do their job otherwise — every effort must be made to ensure that information is placed in the public domain when it is safe to do so.”

So, bottom line here, Snowden’s impetus to blow the whistle on intelligence agency activity overreach in Western democracies is again being vindicated. Even the establishment is admitting spy agency operations have been too murky prior to Snowden shining a light.

Despite the committee’s calls for increased transparency, various details from the report are redacted (as is typical for intelligence agency-related reports) — including, as The Intercept notes, specific case studies provided to the committee by GCHQ to apparently ‘prove’ the efficacy of mass surveillance in preventing terrorist attacks. So there’s no way for the general public to judge for themselves on that point.

The committee also claims to have interrogated the agencies’ use of mass surveillance (which it terms “bulk interception”), as a discovery and/or intelligence gathering tool — and again professes itself satisfied with the legality of the methods, based on these fishing expeditions being limited in scope; the gathered data being triaged and filtered via search terms; and only a small percentage of the resulting communications being read by human analysts.

“Given the extent of filtering involved, it is evident that GCHQ’s bulk interception capability does not constitute blanket surveillance or indiscriminate surveillance,” the committee asserts.

“We have examined cases which demonstrate that bulk interception has exposed previously unknown threats or plots which threatened our security and which would not otherwise have been detected. Therefore, in principle, we consider that bulk interception is an appropriate intelligence-gathering capability that contributes to the UK’s national security – as long as it is properly targeted and controlled,” it adds.

Earlier this year the judicial oversight body for the U.K. intelligence agencies ruled that data-sharing activities between the NSA and GCHQ had been unlawful prior to December last year, on the grounds that they breached European human rights law. However that court also deems the agencies’ current activities lawful — and again the public has to take that judgement on trust, given it is based on non-public court submissions.

The parliamentary committee inquiry also touches on the topic of communications metadata — which, given the associated privacy risks, it recommend should be treated as a separate category — called ‘Communications Data Plus’ — and given “greater safeguards than the narrowly drawn category of Communications Data”.

It also calls for strengthening safeguards specifically associated with the capturing of British citizens’ data (including where Brits are abroad), and improving safeguards around what it dubs “sensitive professions”, such as lawyers or doctors or journalists. On that point, last November it emerged, via a tribunal hearing, that U.K. intelligence agencies had allowed staff to spy on the legally privileged communications between lawyers and their clients.

The principles the committee says should underpin the new legal framework it’s recommending to govern intelligence agencies’ activities are summed up as: “based on explicit avowed capabilities, together with the authorisation procedures, privacy constraints, transparency requirements, targeting criteria, sharing arrangements, oversight, and other safeguards that apply to the use of those capabilities”.

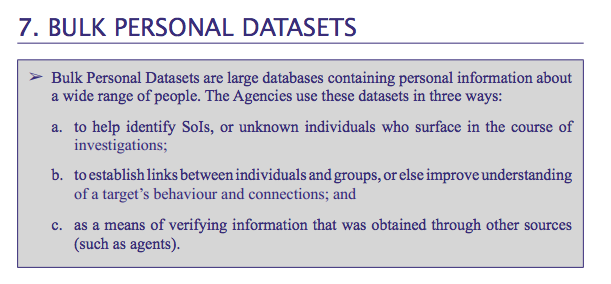

Bulk personal datasets

The committee asserts that its report contains an “unprecedented” level of detail about the intrusive capabilities deployed by U.K. intelligence agencies — including identifying for the first time the use of so-called “Bulk Personal Datasets” (BPDs): aka “large databases containing personal information about a wide range of people” that are used by intelligence agencies to “identify individuals during the course of their investigations, to establish links between Subjects of Interest, and to verify information that they have gathered through other means”.

The Guardian quotes a committee member likening BPDs to “a telephone directory”, albeit one that only focuses on people in ‘a certain category of interest’ to the intelligence agencies.

Information contained in BPDs is clearly inherently personal, but quite how personal is made plainer later in the report — where it is noted that the data can include details such as an individual’s religion, racial or ethnic origin, political views, medical condition, sexual orientation, and legally privileged, journalistic or “otherwise confidential” information.

This section of the report is heavily redacted, including removing details on exactly how many BPDs are held by the different agencies. The report does specify that these datasets “vary in size from hundreds to millions of records”, and can be acquired by “overt and covert channels”.

The report also notes that the rules governing use of these datasets “are not defined in legislation”. So, in other words, they lie outside the remit of existing regulation, like RIPA.

The committee notes several specific concerns relating to BPDs — including that the capability had not previously been acknowledged publicly (prior to its report), meaning privacy issues and other safeguards had not been considered in public or Parliament; that there are no restrictions on how the data is stored, held, shared and so on, and no legal penalties for misuse; and that access to the datasets is authorized internally without Ministerial approval.

(Following the publication of today’s report, The Guardian reports that the U.K. Prime Minister rushed out a statement specifying the intelligence services commissioner, Sir Mark Waller, would be given “statutory powers of oversight of use of bulk personal datasets”.)

The committee’s report directly quotes MI5’s director general claiming that BPDs are not used for fishing expeditions, but rather to follow up on specific intelligence.

In his own words:

… we only access this stuff… where there is an intelligence reason to do it. So we start off with a threat, a problem, a lead, that then needs to be examined and pursued and either dismissed or lead to action to counter it. That is when we use the data. It is absolutely not the case that there is anybody in MI5 sat there, just trawling through this stuff, looking at something that looks interesting; absolutely not.

The extant “policy and process safeguards” used by the agencies to control and regulate access to the datasets entail legal training, audit processes and disciplinary proceedings.

All staff with access to Bulk Personal Datasets are trained on their legal responsibilities; all searches must be justified on the basis of necessity and proportionality; and all searches may be audited to ensure that any misuse is identified.

However the report also notes that all the intelligence agencies have dealt with cases of inappropriate access of these BPDs:

Each Agency reported that they had disciplined – or in some cases dismissed – staff for inappropriately accessing personal information held in these datasets in recent years.