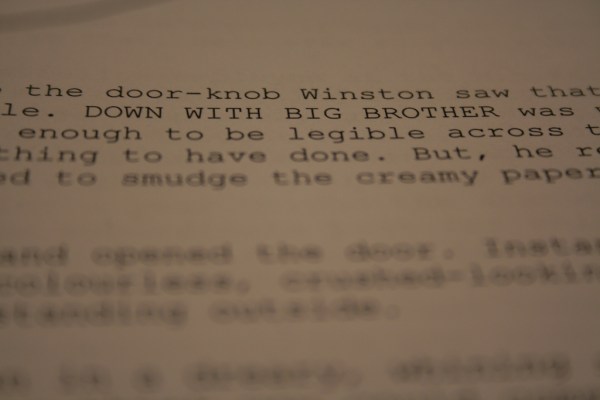

Following a storm of criticism relating to a creepy-sounding privacy policy covering its smart TVs, Samsung has today published a rebuttal and a more detailed explanation of the workings of its under-fire voice recognition feature. It has also edited the wording of its privacy policy to avoid sounding quite so eerily similar to George Orwell’s 1984 dystopia.

The original policy, which has been in place for some months, warned users of Samsung’s Internet-connected TVs:

Please be aware that if your spoken words include personal or other sensitive information, that information will be among the data captured and transmitted to a third party through your use of Voice Recognition.

Which sounded very much as if Samsung were asking its customers to self-censor their conversations when sitting in front of their own TVs in their own homes. An impression that was compounded by the lack of clarity about how exactly Samsung’s voice-recognition feature worked — in terms of when and how it is switched into ‘listening’ mode (so when it’s sending your spoken words to the cloud for other companies to process).

In today’s blog, Samsung stresses that its SmartTVs “do not monitor living room conversations,” and has edited the wording of the policy to excise the offending Orwellian paragraph about sensitive info being snooped upon. Instead it now stresses that user agency is required to trigger the listening feature.

The policy includes the following section explaining the workings of the voice recognition, and also specifying that the third-party processing user voice data is, in this instance, Nuance Communications (I highlighted Samsung’s policy changes in bold):

If you enable Voice Recognition, you can interact with your Smart TV using your voice. To provide you the Voice Recognition feature, some interactive voice commands may be transmitted (along with information about your device, including device identifiers) to a third-party service provider (currently, Nuance Communications, Inc.) that converts your interactive voice commands to text and to the extent necessary to provide the Voice Recognition features to you. In addition, Samsung may collect and your device may capture voice commands and associated texts so that we can provide you with Voice Recognition features and evaluate and improve the features. Samsung will collect your interactive voice commands only when you make a specific search request to the Smart TV by clicking the activation button either on the remote control or on your screen and speaking into the microphone on the remote control.

It’s certainly welcome that Samsung has made it plainer that its TVs do not in fact squat in the corner recording your every utterance. And provided clarity that the full-fat voice recognition feature does not remain on by default but requires a specific user trigger each time it’s used — by the pressing of an activation button.

However, the policy is still rather circumspect, referring somewhat vaguely to “some interactive voice commands” that “may be transmitted.” This vagueness is compounded by the fact that the TV can also process basic “voice commands” without having to resort to a third-party cloud service provider — yet the policy is still fuzzy on the distinction between basic voice commands and more complex speech commands.

The difference between plain old “voice commands” and “interactive voice commands” — in the Samsung SmartTV universe — is in fact clarified by the company in its blog. Here it notes voice recognition takes place in two ways: one being local to the device, with no cloud-processing (and so no third-party data-privacy concerns), and with support for only “simple predetermined TV commands such as changing the channel and increasing the volume”; while the second type of voice recognition supports more complex voice commands, such as the ability to ask the TV to recommend a movie, and does involve data being sent off-site to a third party (Nuance) for processing.

There are also two microphones involved — one in the TV does the basic voice commands (which Samsung says does not record, track or store what it hears, listening only for commands to be spoken to trigger set TV actions); while a second mic, located in the remote control, opens the recording gateway to the cloud.

Its blog notes:

Voice recognition takes place in two ways:

The first is through an embedded microphone inside the TV set that responds to simple predetermined TV commands such as changing the channel and increasing the volume. Voice data is neither stored nor transmitted in using these predetermined commands.

The second microphone, which is inside the remote control, requires interaction with a server because it is used for searching content. A user, for example, can speak into the remote control requesting the search of particular TV programs (ex: “Recommend a good Sci-Fi movie”). This interaction works like most any other voice recognition service available on other products including smartphones and tablets.

As I wrote earlier, the bottom line here is that companies building ‘smart’ services need to be thinking about privacy by design — at the very front and centre of the devices and services they are building — not tacking on auxiliary clauses to catch-all privacy policies which are designed to fly under users’ radars anyway.

Relying on vague wording to obfuscate function and keep users in the dark as to how their technology really operates does no one any favors. It breeds mistrust and triggers overblown concerns. If the privacy policy sounds creepy, the implication is the service provider is also doing something creepy — or at the very least trying to hide its activity from plain sight. Which makes people naturally suspicious.

A further problem here, which Samsung has still not addressed in today’s updates, is that users of its voice-recognition feature also — presumably — become subject to a third-party (Nuance’s) privacy policy. That is not made clear in Samsung’s amended privacy policy. Nor is there a link to Nuance’s privacy policy (which notes, for instance, that Nuance may use information gathered by use of its services for “advertising and marketing”). We’ve asked Samsung about this omission and will update this post with any response.

As the smart home takes shape, consumers are going to be asking increasingly probing questions about what previously-innocuous-but-now-connected-to-the-cloud home gizmos are actually doing with the data they’re sniffing. To keep buyers on side, device makers will not only need great services; they’ll need sparkling privacy and spectacular security too.

A core part of the solution will be privacy by design, and privacy policies written in plain language that are displayed proudly, as an asset, held up in plain sight.

But even those are only partial fixes if the transparency peters out at the gateway to the cloud. It’s not good enough for device makers to pass the baton and the buck to any third-party entities they have looped into processing user data off-site. The parameters of associated third-party operations also need to be made clear to the user. Or that’s just a whole new layer of transparency failure inviting censure.