Olafur Eliasson is an artist who is well-versed in technology. While perhaps not quite a digital native, he has become fluent in the language and tools that technology offers to artists.

As a judge on the Space WIRED Creative Fellowships, Eliasson is ideally placed to straddle the divide between the arts and technology. At his studio in Berlin, he surrounds himself with engineers, coders, technicians, architects and craftspeople — anyone who might help him to realise his vision for an ambitious new project.

“Many of my students at the Institut für Raumexperimente (2009–2014) were skilled programmers,” he says, “and my studio team includes people working with drones and sun-tracking devices and a handful of hackers.”

Not a typical artists’ studio, then. As the boundaries between different disciplines become more and more blurred, the crossovers become increasingly interesting. Eliasson is an excellent example of an artist who is branching out: “I don’t feel alien or excluded when working with digital art. I still ask the same questions: why and how.”

“The next big thing will be an innovation that represents the limitless aspects of digital technologies, something that brings about a seamless, sensorial and spatial interface that still invites participation.”

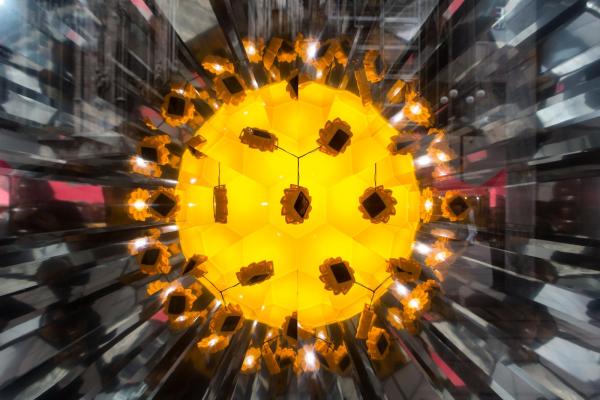

Olafur Eliasson with Little Sun Photo: Tomas Gislason © 2012 Little Sun

In terms of making art, Eliasson is clear that these questions will always come first, and technological tools are there to serve his artistic vision. It’s refreshing to talk to an artist who is confident in his own ideas and who doesn’t see technology as a magic fix – that technology is used to further an idea or to realize a vision. He is pragmatic without losing a sense of the immense possibilities of the future. “I think the next big thing will be an innovation that represents the limitless aspects of digital technologies, something that brings about a seamless, sensorial and spatial interface that still invites participation.”

A lot of Eliasson’s work is participatory or requires some kind of input from the audience. For him, what is exciting is reaching “the moment where the fact that it is digital will go unnoticed, and the fact that it is art will be the focus.”

Far from worrying that the arts might get left behind with technology moving as fast as it does, Eliasson feels that “very often, art is capable of moving a lot faster, into deeper places. Art has an ability to work in a very cross-pollinating way. The authorities, the lack of law in the digital world, it is all so slow. By the time someone comes up with some rules about the Internet, for example, the artists will already have been there and worked on ethics and aesthetics and social impact for a long time.”

One of Eliasson’s current projects, Little Sun, has had a huge social impact. Working with engineers, Eliasson has designed beautiful and highly functional solar-powered lamps, which are being distributed in places without other forms of electricity. The lamps allow children to study despite the darkness, and the potential for opening up education and opportunities is huge. It’s an art project entirely made possible by both collaboration and an understanding of the available technology.

Little Sun, Addis Ababa, 2012. Merklist Mersha, Olafur Eliasson Studio.

“I stay in the loop through Little Sun, which relies on new digital and social media approaches to make its work and vision visible. I also like to keep a track of what the Center for Civic Media at MIT is working on, and I follow Evgeny Morozov’s work, too (usually on the plane). And of course, who can get through a normal day without looking up a few questions on open source tools like Wikipedia?”

Eliasson, who has also made enormous installations such as the Weather Project at Tate Modern, where a giant “sun” illuminated the Turbine Hall, is interested in the possibilities that new technologies and collaborations can open up. By being open-minded and by working with a range of people, he is broadening the possibilities of what digital technology can do for the arts, and vice versa.

As technology continues to develop at breathtaking speeds, what impact does this have on the artworks Eliasson and others are making? If the technology upon which something is based becomes superseded or obsolete, does the artwork automatically become obsolete, too?

“It’s a little more complex than that,” says Eliasson. “I think some paintings can become obsolete… if you look at paintings through history, I think the tendency is for them to become obsolete. If you look at what we preserve in museums, it’s only a tiny fraction of those painted.”

Little Sun, Milan, 2012. Marco Beck Peccoz, Olafur Eliasson Studio.

He has a point. But surely he is concerned about making work that has enduring appeal and value?

“If you make a relevant work of art, it resonates, and in some ways produces the reality that it is a part of .… a great work of art is a reality machine. Now, as time changes, the definition of reality is also changing. Some works of art have the skill of adapting to new times, and they might resonate in a different way. That remains a great work of art. Other works of art fade… they have performed their value in a shorter time slot. We should be careful not to say which is the greater work of art.”

Jeremy Deller’s work for The Space, for example, was specifically designed to only be seen for a short time: in the run-up to the centenary of the outbreak of WWI, Deller produced a series of short films, one of which was only available for an hour to mark the actual start of the war.

Eliasson says: “The definition of a great work of art is not necessarily how long it stays relevant to the world. Yes, it’s exciting that a piece of art can somehow reinvent itself as a reality machine, but that doesn’t mean that a work of art that only has a flash of relevance is then an unimportant work of art.”

“What I’m afraid of is that there’s a kind of obsessive focus on how to spread news or artworks, but very little focus on the content.”

Is he excited about any specific innovations at the moment? “I am excited by anything that brings increased focus and an awareness to our interactions in virtual space and where seamlessness of content allows for this focus. I think my collaboration with Ai Weiwei is a good example of this.

“Weiwei and I created the artwork Moon to be an interactive tool that allows users around the world to leave their own mark on the surface of a virtual moon. It connects people across not only vast distances but also political, social and geographical boundaries.

“At present, I am also keeping an eye out for the new app Wire, which is an outlet with a strong focus on content, debate and discussion of global issues.”

But he also has concerns. “I am discouraged by technology that increases our attention deficit and only adds ‘white noise’ to virtual space and to our lives. It’s a shame when social media innovations aren’t used for productive engagement, because they can be such powerful tools for change.”

“We have an economy that seems to have lost total track of the need to know why before you focus on how. What I’m afraid of is that there’s a kind of obsessive focus on how to spread news or artworks, but very little focus on the content. There are no processes. I don’t have the answer, but I’m curious about what applications, what tools, what skills will guide and amplify.”

Editor’s note: Eleanor Turney is Managing Editor of The Space and Co-Director of the INCOMING Festival. She has written for publications including The Guardian, The Stage and the Financial Times. The Space is a website for artists and audiences to create and explore new art, commissioned by the organization, and shared around the world.