Editor’s Note: John B. Rogers is chief executive and co-founder of Local Motors, which designs, builds and sells vehicles through the use of co-creation and microfactories in Chandler, Ariz., Knoxville, Tenn., and Las Vegas.

There’s a new vanguard creating the future of the U.S. manufacturing economy.

Companies like MakerBot, TechShop and Kickstarter are playing a large part in fixing the breakdown between historical industrialized employment and manufacturing models, which people still depend on for work, and the more flat and networked world in which we now live.

Part of this interrogation into the industrial manufacturers of tomorrow needs to involve looking at assumptions about financing and the actual mechanics of manufacturing. Fundamental assumptions need to be reformatted in a new way to win.

At my company, Local Motors, we have a saying: If you want to make local big, you have to make big local. If we bring manufacturing of big hardware (home appliances, vehicles) within 100 miles of the most densely populated areas in the world, we can not only rapidly meet those communities’ needs, but we can increase the pace of product innovation, both while creating meaningful local jobs.

I spent three years in China where companies like Foxconn built huge cities that can make any small hardware device – anything that fits in a shoebox. It’s easy to produce, easy to warehouse and inexpensive to ship. But if you want to produce large consumer goods, you’ve got few places to go and even fewer places to go for capital. The tools and parts don’t ship well, they are expensive, and the cost of mistakes can be very high.

The good news is, we’re developing an ecosystem around entrepreneurial endeavors that is leading us into the third Industrial Revolution.

A Quick History Lesson

The steam-powered Spinning Jenny, followed by the petroleum-powered version, led the first Industrial Revolution. If James Hargreaves hadn’t invented the Spinning Jenny, we wouldn’t be wearing the clothes we have today. Henry Ford led the second Industrial Revolution in the 20th Century with large assembly-line factories being built on a mass economy of scale. This second industrial revolution was refined by Toyota’s Kaizen process of continuous improvement and, later, lean manufacturing and Six Sigma process control.

The third Industrial Revolution is what I call a product of the very recent Internet-applied-to-things (not the overused phrase Internet of Things). More specifically, it is applied to three things: access to information at unprecedented speeds, reductions in the cost of professional tools and meaningful legal protections.

Its hallmark is that of a flat and distributed economy, a level playing field where local enterprise can compete with global conglomerates. The proponents of this movement are empowered to defy conventions and to share ideas globally at an unprecedented rate.

Rapid Access to Information

I can visit Thingiverse and download an STL file of a door grommet, send it to a 3D printer and within hours it’s printed and installed on my car door. Our community has users who upload and exchange ideas on vehicle innovations. GE Appliances is building a microfactory called FirstBuild with the goal of speeding appliance innovations to market by opening up the process to the brightest minds from around the globe.

Cut the Cost of Tools

Makers can access expensive professional tools through companies like TechShop where you can access large computational power/storage and machines like 3D printers, for example, for an hour at a time. Or lease, instead of own, expensive additive manufacturing equipment through companies like Cathedral Leasing.

Federal institutions like Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee bring innovative researchers and the private sector together and provide access to super computers and the ORNL Manufacturing Demonstration Facility to solve the most pressing challenges facing manufacturing today.

This is a revolution because you can bring hardware and software to market at unprecedented rates with a much smaller amount of capital through crowdsourcing, crowdfunding and microfactories.

Meaningful Legal Protections

Today, in the U.S., we have legal protections for user-generated content that now mean something. We have Creative Commons, MIT, GNU and other open-source licenses that grant users more free rein to modify – and sometimes market – software while protecting attribution and creators wishes.

Microfactories

Microfactories are meaningful because of their size, accessibility, and low cost of capital.

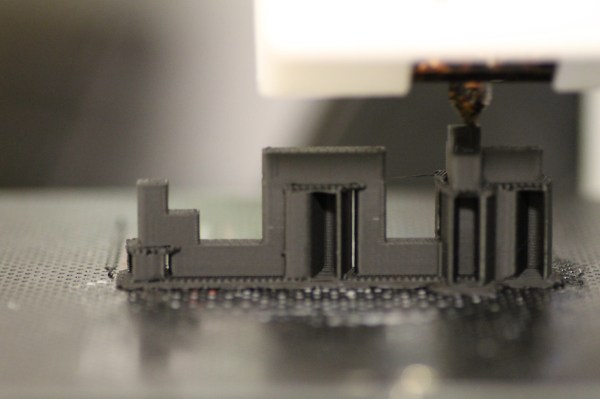

If you set up a micro-manufacturing facility and you are making something big in size, you have a running shot to make it work. Why? Because microfactories move concepts to products faster by using crowdsourcing for the design and 3D printing for the manufacturing.

Crowdsourcing rapidly taps into a global talent pool of people who can solve any particular engineering challenge faster. 3D printers use less material, generate less waste and manufacture products faster than traditional factory processes. This means less space and materials are required to manufacture products, resulting in a significant reduction in capital costs.

Microfactories reduce negative impact on the environment by reducing waste, creating jobs, reducing freight and distribution costs and speed time to market.