On the eve of the Apple Watch announcement no one was really sure what to expect. A concerned watch industry insider had called me a few days earlier and asked what I thought. His bosses were concerned, but not overly so, and he wanted some details. No one had any idea what the thing would look like but his bosses wanted some intel. I had none to give.

The night before the launch I asked a friend who had insider knowledge about the product. I posited that the watch would be something you wore on one wrist and that I could wear my beloved mechanicals – my massive Bell & Ross, my Speedmaster Mark II, and my world timer Jaeger-LeCoultre – on my other wrist. I’d be a little like Nicolas Hayek, the beloved CEO of the Swatch Group, now deceased, who used to wear all of this sub-brands’ watches on both wrists.

My friend shook his head.

“You’ll wear this as your only watch,” he said. He said it was a fashion item, something that would sell out immediately.

The announcement was a surprise to everyone. It was a typical “One More Thing…” moment. Tim Cook was excited to announce something to us. His language was folksy and calm. Then the video started. It was Kubrikian – the earth cresting into sunlight, city lights winking out as the sun rose above the wilderness. Off to the right something appeared – silver with a little round divot that slowly materialized into what looked like a crenelated crown. On the other side, another button, gently recessed. Something that said “STEEL” and then four little eyes that looked like the bug-peepers of an angry Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator. The music was organic with a touch of electro, a sound like dogs barking rolled in at the juncture featuring that same crown spinning back and forth and affecting the watch screen. Were those icons? Were those apps? Was this a watch or something for future humans to ingest before drifting into CryoSleep?

It’s a watch. More scenes of the technology. The Earth motif is forgotten as the watch takes center stage. There’s the band, there’s the bracelet. There’s a little icon that brings up a timer. There are ways to communicate with friends with touch and doodles. This is the new Earth, the new heavenly body born out of the darkness that lands in a white room as an unseen hand actuates function after function – a rose blooming under a clock, a step meter spiraling into view, Mickey Mouse tapping his toe jauntily. My god, it’s full of stars.

It was enough to make a fanboy ravenous. For me it cemented the idea that this was the rebirth of the watch and Switzerland, that longtime citadel of tradition and commerce, was lost. I posited — and still posit today — that if anyone is going to bring back watch wearing, it will be Apple, and that the Apple Watch will replace the traditional quartz fashion watch on wrists around the world in all different countries and across demographics.

After seeing the Apple Watch, after understanding its capabilities and connecting the iOS dots, it was clear that this was more than a sports band. It was a watch, designed as a fashion item as well as a tool. It was a timepiece second, a communications system first, and it was clear there was interest in many camps, from those who had not worn a watch in years, the so-called smartphone generation, to folks entrenched in the mechanicals industry.

And as a watch lover, I’m worried. On the eve of the Apple Watch launch, I’m increasingly convinced that this will replace my mechanicals in many cases. It’s a hard thing to for me to say, personally, and it’s a hard thing for fans of mechanical watches to accept. However, as a mass phenomenon and an engine for societal change, we’re going to see the return of the wristwatch and none of those timepieces will come from Switzerland. They will come from China via Cupertino and the implications on the watch industry will be enormous.

If the Apple Watch fails – and it won’t – the Fossils and Calvin Kleins and Burberrys of the watch world have nothing to fear. If it succeeds, there will be a massive shake-up of the sort and scale not seen since the quartz crisis of 1979.

But first let’s look at where wristwatches began – and where they are going.

The first wristwatch, a small silver-cased timepiece with blued hands and a ribbon band, was built on a whim. In 1810 Napoleon’s sister, Caroline Murat, requested a watch that could be worn on a thin band of hair and gold. Breguet, a grandmaster watchmaker then fallen on hard times, was hungry for the lucrative commission and built a surprisingly small minute repeater – a watch that chimes the time – in about two years. Murat, the Queen of Naples, bought many more Breguet’s but all of them were pocket watches, a form that sustained the watchmaking industry until World War I. Men, after all, preferred pocket watches, calling wristwatches “wristlets” fit only for women.

By 1900, however, the utility of the pocket watch was waning. The attendant rough conditions during wartime and global exploration found many men fumbling with their candy-tin-sized pocket watches under hard conditions. Sailors began wearing wristwatches on board and, as the first bombs burst over WWI trenches, Hamilton began building the first mass produced wristwatches for a generation of young Americans. “The most reliable timekeeper in the World for Gentlemen going on Active Service or for rough wear,” went one British wristwatch ad. A decade later and the wristwatch was ubiquitous, the the mechanical, ticking equivalent of a smartphone.

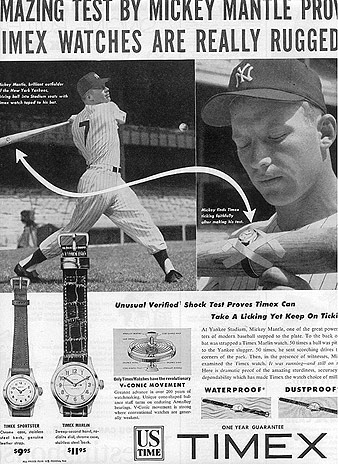

The brands we know and love today – Timex, Rolex, Omega, Brietling – got their start as mass-market products. A $150 Rolex, in 1957, was an expensive watch for the time – about $1,200 in today’s money – but it wasn’t unattainable. Timexes were $12 and took a licking while Swiss watches weren’t that much more expensive. When everything had to be mechanical there was no specific benefit Swiss craftsmanship or design and business was good for decades.

On December 25, 1969, the Japanese watch company Seiko released the Astron 35SQ, the world’s first analog quartz watch. Quartz clocks were’t new. A quartz crystal, exposed to an electric current, would vibrate at a constant and predictable rate, and that this property could be exploited to keep time. Quartz movements were more accurate than their mechanical counterparts and had the added advantage of being impervious to shocks (to a degree). It had taken Seiko more than ten years of R&D to bring its idea to market and the Astron initially cost, $1,200 – as much as a lower-end car.

The Astron’s ticking second hand was a revelation for many. It was the future. After a limited run of 100 pieces, Seiko perfected the watch and began to sell improved models using integrated circuits. Prices dropped precipitously. Within seven years, Texas Instruments would debut the first quartz watch priced under $20.

The world flocked to quartz. These timepieces, so much simpler to make without the endless gears and cogs of mechanicals, could be stamped out in seconds, and thousands of them flooded the bars and clubs of the 1970s.

The effect on on the mechanical watchmakers was immediate. Orders fell. Factories idled. Quartz was king and the Swiss were in crisis.

The old watch companies were dinosaurs. The devastation wrought by quartz on the traditional mechanical watchmakers was similar to what would happen to cameras, as consumers abandoned their high-end Leica shooters and low-end Nikons, not to mention the rolls of film that fed a thousand sprockets, for digital cameras.

Swiss watchmakers could have adapted. Around 1970, as the first mass-produced quartz watch movements began flowing into Switzerland, its artisans played an important role in reducing the size and complexity of the movements for placement into wristwatch cases. But whether due to a lack of foresight or a distaste for all things electronic, most Swiss manufacturers ignored the technology. They knew dials and gears, not transistors and batteries. The quartz peddlers soon left Europe for Japan, and stayed there.

The Swiss clung desperately to their past greatness, and an entire industry arose offering COSC-certified watches that had been tested extensively for accuracy over a long period of time. The COSC designation enabled some watchmakers, like Breitling, to charge more for their watches. But it did nothing to restore Switzerland as the center of watchmaking. They were down, but not out.

In 1972, a Swiss company released a watch that would eventually carve a path back to relevance for the industry. For years, watch luxury had meant gold; steel was the pedestrian metal reserved for low-end bar mitzvah gifts. But the porthole-shaped Royal Oak, from Audemars Piguet, was a luxury quartz steel watch for the polo set. Soon Breitling and Rolex followed suit, charging $8,000 and up for steel watches, which once would have been unthinkable. In the go-go 1980s, the trend took off, and Swiss watchmakers, along with mechanical watches, experienced a renaissance by embracing a new sense of mass luxury, adding odd colors and lots of shine to their designs.

It should be noted that this was essentially capitulation and not every company followed suit. Old watch companies like Chopard and Breguet nearly went out of business during the quartz crisis as their CEOs refused to join in the quartz craze.

In the 1990s, luxury mechanical watches had come back into vogue in a big way. Rolex, once the only name that came to mind when one thought of high-end watches, was now joined by relative upstarts like Panerai, Omega, and Breitling, in addition to the more venerable firms dating back centuries. $14,000 for a single watch came to represent the low end. Watchmaking was back and Switzerland became, once again, the watchmaking capital of the world.

Slowly watch houses that were associated with quality – Rolex, Omega, Tissot – became associated with luxury. Quartz was for peons, for folks who frequented discos (recall the “Time To Make Love” watch featured in Auto Focus). But it wasn’t enough to properly buoy watch houses and maintain the extravagant lifestyles of the old money watch CEOs. That is until Nicolas Hayek came along.

Born on February 19, 1928 in Beirut, Lebanon, to a well-to-do Lebanese-Greek Orthodox family, Nicolas Hayek began his career as a corporate consultant tasked with turning around two Swiss watch conglomerates, the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie (ASUAG) and the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH). Both had been founded in the early 1930s and survived for decades. Between them they owned an array of major brands, including Omega and Tissot, as well as ETA SA Manufacture Horlogère Suisse, shortened to ETA, an ebauche factory founded in Neuchâtel in 1793. ETA’s inexpensive, mass-produced Swiss movements had become industry standard, appearing in almost every watch made between the World Wars, and until quartz took over the industry, the company effectively controlled the watch market for six decades. By manufacturing mechanical and quartz watches, the company was able to limp through the crisis, but barely. ASUAG also owned Nivarox-FAR, the largest maker of hairsprings in the world. In short, these two companies were the embodiment of the Swiss watch market and were, when Hayek came along, failing.

Hayek, who studied math and science and founded Hayek Engineering AG in 1979, was an extremely shrewd businessman. Charged with writing a report about the two conglomerates for the Japanese company Seiko, he instead recruited a group of investors, merged nineteen smaller watch companies that were floundering, and took ownership of the resulting corporation, which he eventually named the Swatch Group. A cantankerous businessman, he quickly blew through the staid and stodgy Swiss watch business like a human tourbillon, insulting rivals and exhorting his employees – numbering 24,000 in 2009 – to greater heights. “One day a president of a Japanese company in America said to me: ‘You cannot manufacture watches. Switzerland can make cheese but not watches. Why don’t you sell Omega for four hundred million francs?'” he told the Wall Street Journal. “I told him ‘Only after I’m dead.'”

Hayek conceived of the new company as a manufacturer of “emotional products,” so charged with romance that they became objects of desire and nostalgia. He saw in his products a projection of the Swiss heritage. Wrapped up in the tiny metal cases of his luxury brands like Omega and Tissot were centuries of Swiss tradition. In the bright faces and wild colors of his Swatch brand he saw the fun and rebirth of a reunited Europe. He viewed watches not as a mass-produced commodity but as heirlooms, signs of status, and a respect for tradition all rolled into something that could cost as little as $100 — in the case of a Swatch — or as much as $30 million.

“If you are an emotional consumer product, if you lose the lower market segment, you lose everything,” Hayek told me. “Look what the British did. They decided that they didn’t want to mass-produce cars, so in America you had General Motors, and the British kept Jaguar and Aston Martin, two high-end brands. Well, in the expensive market, you do not have a way to make money anymore. If you do not control the lower market segment, you do not control the overall market.”

The lower end of the watch industry had come to be dominated by quartz models from Japan, with movements designed by an engineer from Texas Instruments. The Swiss, in Hayek’s view, had chauvinistically rejected the American movements, to their own detriment. The Japanese, unburdened by snobbish tradition, welcomed the American-made movements and “took over the reputation of being the most accurate watches in the world, and in less than one and a half years, we had zero market share in the low end.”

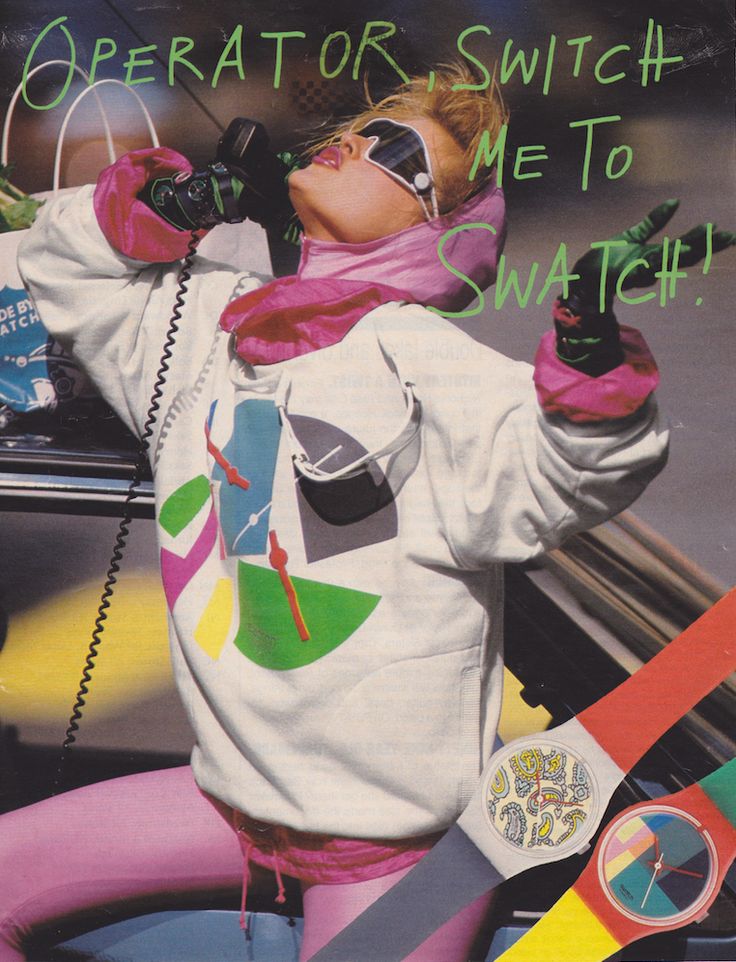

Hayek sought to reverse this trend. First, he and his team, including watchmakers Elmar Mock and Jacques Muller, created a simple quartz movement with 51 pieces instead of Japan’s 151. The goal was to reduce the possibility of failure in a quartz watch. Because they were already so accurate, the only obvious way to improve them was to make them stronger and cheaper. Muller, wondering why no one on the beach wore a watch, realized that they were stodgy and, more important, too expensive. The simple Swatch, with a quartz oscillator and a small actuator to move the hands, welded on a single circuit board, was his answer. The Swatch team would change the line once every six months, having the faces and cases designed by artists of the day (most famously, Keith Haring). The whimsical, low-end quartz watches gave Hayek an instant hit.

In 1982, when they launched the brand, they sold out the initial run of seventy thousand pieces in fifteen days. In 1983, the group sold one million watches, and by 1986 they had sold twelve million units. Collectors often bought two, one to wear and one to keep in its original package, and fans camped overnight outside of stores before new releases. Some rare Swatches, such as an oddly shaped fish-themed watch called the Andrew Logan Jellyfish, now sell for in excess of $20,000, not a bad return on an original $30 investment.

Although Swatches proved a fad, it was a lasting one, and their success sustained the Swatch Group’s collection of older firms, including Breguet, through the quartz crisis. “I needed to keep my people in jobs at my ninety factories,” Hayek explained later. “And to have work, you needed volume, and volume was only achievable with watches like Swatch.”

Once he had stabilized the Swiss industry, Hayek turned his attention to his prestige brands. Watchmakers were born, lived, and died in the Vallée de Joux where most of the prestige names – Breguet, Omega, Audemars Piguet – where headquartered and there was a “Vallée mentality,” as Hayek saw it, a method for doing one thing one way and never deviating from the path. It was his goal to shake things up, to create new movements, complications, cases, and watches that had never been seen before but still had a strong link to Breguet’s earlier, best-known work. He mined records for odd watches to reproduce in miniature. Twenty years after the quartz crisis the industry was flush. Cheap “fashion” watches buoyed the prestige brands, allowing all the marketing money to flow upward. While Swatch didn’t have to advertise (try to remember the last ad for a watch you saw), the more expensive brands did. Each brand – most now owned by either Swatch Group or Richemont – positioned itself in a different niche. Breitling aimed for the clouds with photos of jet plans and steely-eyed John Travolta. Omega advertised at sporting events where the monied gathered and talked up the fact that it was an Omega Speedmaster, not a Rolex, that ticked on the wrists of the first men on the moon. Patek Philippe flew high above the fray, offering a vision of a father in boat shoes passing his beloved PP on to his tousled, sun-dappled son.

All was right with the world.

We see then that the Swiss can save themselves by pushing their watches even further into orbit, like humanoids escaping a parched planet. While none of the Android watches have quite fired the imagination, I see time when when wearables will become our daily drivers, things that sit on our wrists permanently until subcutaneous systems become popular. Wrist real estate is precious and when a teenager of relative means looks at a $500 smart watch that allows him or her to send secret love letters to their sweetheart versus a $500 dumb watch in Burberry plaid, the decision will be quick and painful.

The decision will wipe out the lower end that has always bolstered the prestige brands. This will, in turn, push prices higher in the prestige brands and force the manufacturers to concoct new marketing plans to win back customers who, like, might replace a beautiful, handmade Omega with a robot-made Apple Watch. The watch fanatics all say the same thing: “We buy watches for a different reason. We buy watches because we love the art, the artistry, and the design. We love the history, the provenance. We didn’t stop buying Bordeaux because Zima came along!”

But what happens when something comes along that renders Bordeaux growers hopelessly stranded and without financial supports? What happens when even Zima gets crushed by something new and strange. I understand what the fanatics are saying for I am one of them. But I also see this as an iPod moment, a moment that will fracture so many industries simultaneously that all survivors will be mortally wounded. There is no one mourning Creative or Archos or Rio. There is no one pouring one out over the compact disc’s mausoleum. Instead incumbents have learned to survive in a new environment and my fear is that the Swiss can only survive by pricing up. They don’t have the skill to enter the wearables fray or they would have already done it. It’s unfortunate but true.

In the end I’d be glad to be rid of fashion watches, to watch those unctuous mall kiosks selling cheap quartz shrivel like ferns in the sun. They are an affront to the long history of watchmaking that I cherish and consider one of mankind’s crowning achievements. Watches have ridden in Napoleon’s side pocket and in Ghandi’s robes. They timed the D-Day attack and the labor contractions of countless women over the past century. They were used to circumnavigate the globe and reach the stars. And they deserve respect and the industry that builds them deserves to thrive. But something is about to happen to that industry, something strange and irreversible, that must be addressed. The more we hide from it, the more the Swatch Group and Richemont ignore it, and the more collectors scoff at it, the further we move from saving the whole thing and the closer we are to collapse.

Some of the research and all of the the interviews in this piece came from my forthcoming book on watches and watchmaking.