What if Silicon Valley had emerged from a racially integrated community?

Would the technology industry be different?

Would we?

And what can the technology industry do now to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past?

I met Bob Hoover one sunny Friday afternoon when he was rearranging golf club sets in the back of a trailer in East Palo Alto.

I met Bob Hoover one sunny Friday afternoon when he was rearranging golf club sets in the back of a trailer in East Palo Alto.

Hoover, one of the original black residents of East Palo Alto, hasn’t retired even though he’s well into his 80s. He splits his time between teaching golf to the children of the neighborhood and counseling former prisoners on re-entering the workforce.

The city where Hoover lives, East Palo Alto, is the last 2.5-mile stretch of affordable housing in the heart of Silicon Valley. It is perfectly wedged between the new Facebook headquarters, the rest of Menlo Park, where the venture firms of Sand Hill Road are based, and Palo Alto, where the tech industry first sprouted around Stanford University more than half a century ago.

Map: Jake Coolidge, created at the Stanford Spatial History Project

East Palo Alto has been portrayed as a haven of affordability for a low-income and primarily black and Latino community and alternately as a stubbornly intractable core of poverty and violence amid Silicon Valley’s glittering wealth.

In 1992, the city earned the moniker “Murder Capital of the U.S.A.” after having the highest homicide per capita rate in the country. Three years later, its high school students became the center of the Michelle Pfeiffer movie “Dangerous Minds,” with the Coolio single “Gangsta’s Paradise” on the soundtrack.

But today, with Facebook constructing a Frank Gehry-designed office complex that will let the company support roughly 7,000 workers while Palo Alto and Menlo Park balk at building housing even though median home prices have soared beyond $2 million, East Palo Alto may change enormously over the next decade.

Moreover, the questions being asked today about why the tech industry lacks racial diversity, and what the long-term consequences of gentrification are in the U.S.’s most economically vibrant regions like the San Francisco Bay Area are deeply intertwined in a way that is hard to perceive unless you step back.

This is a story of how two neighboring communities followed entirely different trajectories in post-war California — one of enormous wealth and power, and the other of resilience amid deprivation. It’s about how seemingly small policy choices can have enduring, multi-generational consequences.

A year ago, I told you my family’s history in Silicon Valley. Let me tell you another story.

1950s: Residential Segregation In What Would Become Silicon Valley

A U.S. Air Force veteran who served on a gunner crew in the Korean War, Bob Hoover came to the Bay Area in 1959 as a young master’s degree student at Stanford University. His wife was earning her doctorate from Stanford’s department of education.

He arrived in Palo Alto at roughly the same time as my grandfather. But my grandfather, who grew up in a poor Jewish family in Los Angeles during the Great Depression, was white.

Hoover was black, which means he couldn’t live wherever he wanted. He would dial up dozens of apartment listings.

“You’d call them, ask them if the apartment was available. They’d say yes,” Hoover said. “But when I would show up and they’d see my face, they would suddenly say it had ‘just been rented’ or something to that effect.”

Hoover’s experience wasn’t uncommon. Homes at the time often had deed restrictions written into their contracts that explicitly prohibited their sale to African-Americans.

In fact, East Palo Alto’s existence as a predominantly black community probably began around 1954.

That fall, a man named William A. Bailey and his family became the first blacks to move into a new subdivision called Palo Alto Gardens. The Bailey family’s arrival on the 150 block of Wisteria Drive touched off protests from neighboring white homeowners. One hundred twenty-five people packed the normally quiet Palo Alto Gardens Improvement Association on November 29, 1954, to express outrage over the idea of a black family moving into their neighborhood.

When the association’s president William Diebel pushed for tolerance and acceptance, its white property owners threw him out and began drafting a “gentlemen’s agreement” requiring that all prospective buyers be approved by the association.

They also pooled together $3,750 to convince Bailey to leave. But when he refused with backing from the NAACP, one-fifth of his white neighbors immediately put their houses up for sale and left.

The same issue affected Asian-Americans. When progressive suburban developer Joseph Eichler’s company sold a home in 1954 to an Asian-American family in Palo Alto, word spread through the neighborhood and five homeowners approached the company demanding immediate refunds.

“Get out,” Eichler’s business partner, Jim San Jule, told the white homeowners. “We don’t even want people like you in our subdivisions.”

Hoover had tried to buy an Eichler home in Palo Alto too, but no one was willing to sell to him. Decades later in Walter Isaacson’s biography, Steve Jobs, who grew up in a Modernist suburban tract home designed by an Eichler competitor, would later credit Eichler’s architecture with inspiring him to produce minimalist designs for the masses.

Hoover and Bailey had come to California as part of the Great Migration, a movement that saw 6 million African-Americans leave the violence and humiliation of the South for industrial cities in the North and on the West Coast.

Gertrude Wilks was one of them. She was born on a plantation in 1927 as the child of Louisiana sharecroppers. When she was a child, she said, her mother would reveal scars on her body from an attempted rape, as a warning never to get caught alone with a white man. She remembers teaching her father how to read. She remembers seeing him write his own name down for the first time.

Wilks, who moved to Richmond with her husband when she was 20 years old, later convinced the entire family to move out of Louisiana. Her father and brother had ended up in a fight provoked by a white neighbor, who then threatened to burn down their house in retribution. When she found her family, they had been sleeping in the woods near the house. Their cow had been poisoned, their hogs and most of their dogs had been killed. One brother had been shot in the leg.

California was better in certain ways.

“You could really be free,” she said. Wilks’ father was able to vote for the first time when he arrived in Los Angeles.

But the state was “not so golden,” as she put it. California was never as overt or horrific as the Jim Crow South. But the Californian way worked tacitly through housing, jobs and education policies. On top of racially restrictive covenants, realtors around the San Francisco Bay Area were engaged in a practice called blockbusting. Hoover remembers it well.

“They’d come in and say there’s a black man going to buy a house here. You’re going to have a hard time selling your house, so you better do it now,” he said.

Real estate agents would buy the houses at fire-sale prices, then turn around and sell them to African-Americans for a profit. Wilks remembers a real estate agent steering her away from buying a home she liked in Palo Alto. She later found out that she could have afforded it, but had already ended up in East Palo Alto.

By the mid-1960s, East Palo Alto had gone from being almost all white to being majority black. Then when the federal government widened Highway 101, the main artery between San Francisco and what would become the rest of Silicon Valley, that deepened both the physical and cultural divide between the two areas.

To top it off, Palo Alto annexed the lands directly to the south of East Palo Alto for a golf course and an airport. East Palo Alto would instead end up with the Romic waste management facility, which opened in 1964. It would process hazardous chemicals from semiconductor and hardware production in Silicon Valley for decades, sometimes leaching cyanide into the city’s sewage water and spraying chemical mists above the city during periodic accidents.

Meanwhile just three miles away, Stanford University had been struggling financially since World War II. The university’s reputation and endowment wasn’t what it is today — certainly not the elite institution that railroad tycoon Leland Stanford envisioned building when he signed Stanford’s founding grant in 1885.

The name “Silicon Valley” wouldn’t even exist for another 20 years.

But Frederick Terman, the Stanford dean of engineering credited with transforming the school into a locus of power within the tech industry, had a couple key insights. He had returned to California after finishing his Ph.D. at MIT under Vannevar Bush, who pushed for the creation of the National Science Foundation and wrote an influential 1945 essay on the “Memex” that would shape the concepts of the mouse, hypertext and links many decades later.

With his connections to Bush and the East Coast, Terman saw that Cold War research money would become a valuable source of capital for Stanford’s engineering school. Under his leadership, the value of government grants and contracts to Stanford grew from $3 million in 1951 to over $50 million in 1964.

Then, he thought that Stanford could use its plentiful land to kill two birds with one stone by turning some 200-plus acres into Silicon Valley’s first industrial park. An architectural precursor to many of the suburban corporate campuses throughout the region, the park cultivated the symbiotic relationships between industry and academia that Stanford is so well-known for and brought in revenue through commercial rents. Many of the industry’s most influential companies would move in, including Varian, Hewlett-Packard, Lockheed’s space and missile division, and Xerox PARC.

While Stanford did start to push for more minority student enrollment in the 1950s, racial attitudes were very different at the time — even in progressive California. Both Terman’s father, who popularized the use of IQ testing nationally, and Nobel Prize winner William Shockley, another seminal figure in Silicon Valley history who was behind the creation of the transistor, were outspoken eugenicists.

1960s: Black Power and The Civil Rights Movement

The new black community forming in East Palo Alto had little in resources, but residents did what they could to build their own institutions.

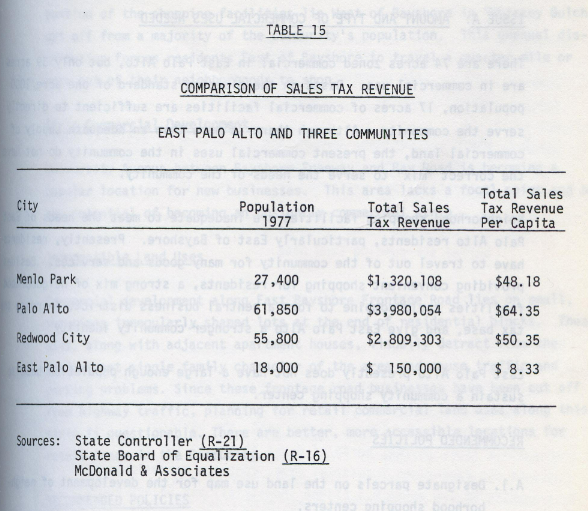

An unincorporated zone of San Mateo County, the area had just a fraction of the tax revenues per capita that the surrounding cities did, as wealthier, middle-class whites fled and took their incomes and capital elsewhere. While the sales tax data below is from a decade later, it gives you a sense of the disparity.

East Palo Alto was bringing in about one-fifth of the sales tax revenue per capita that Palo Alto and Menlo Park were.

East Palo Alto had about one-fifth of the sales tax revenue per capita to support its public services and schools. Source: San Mateo County, 1980

In a 1968 application that San Mateo County wrote for a grant from President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Model Cities program, it said:

“The adjacent cities do not desire to annex East Palo Alto with all of its costly problems such as unemployment, low level of income, overcrowded housing, low education attainment, high number of welfare recipients (highest in the County), drainage, street repair, and lack of certain facilities.

The real problem of East Palo Alto is one of non-integration of the Negro into the affairs of wider society. The Negro of East Palo Alto has not been able to express himself within the hierarchy of communication that would bring about his desired action. Therefore, his desires have been frustrated.”

In spite of the lack of resources, East Palo Alto community members and blacks across the San Francisco Bay Area pushed back against discriminatory housing practices, built schools and lobbied for access to jobs at the peak of the Civil Rights era.

Building schools

Wilks put her children in the Ravenswood School District. The lone high school the district had built in East Palo Alto had a student body that was 90 percent black, but the teachers and administration were 90 percent white. In the 1950s, the NAACP had resisted this districting, arguing that East Palo Alto was falling behind a “concrete curtain.” But they weren’t successful.

Even though her son was getting good grades, Wilks realized the curriculum her son was being taught wasn’t even going to lead to literacy by the time he graduated from high school. She became vice president of the PTA and would overhear teachers say, “It is no use bothering to give them work. They just don’t care and neither do their families. Most of them have no fathers.”

Feeling educationally cheated, Wilks organized a “sneak out” program with other local moms and white friends from neighboring Palo Alto to get 100 local children into their better-resourced schools. She then founded the Nairobi Day School to give kids supplementary weekend tutoring in reading.

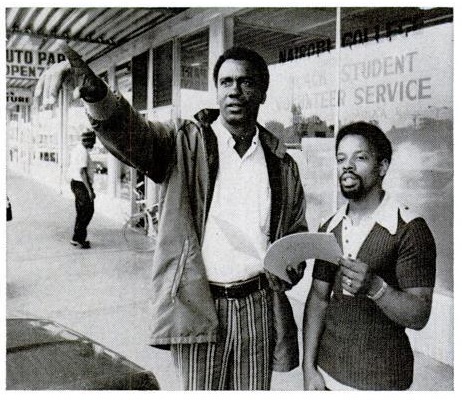

Gertrude Wilks (right), the daughter of Louisiana sharecroppers, moved to East Palo Alto and was one of its most prominent leaders in the 1960s. She was involved in the movement to get Stanford University to implement affirmative action.

Bob Hoover’s then wife, Mary, who had done her doctoral work at Stanford on language, formed an entire methodology for teaching literacy to black students called the Nairobi method.

But the “sneak out” program wasn’t the answer, either. One afternoon, a white man followed Wilks’s daughter and two of her daughter’s friends into the women’s bathroom at Cubberley High School. While holding a gun in his hand, he used a racial epithet that had been scrawled on their lockers and told them to “go home.” Wilks knew of an empty house and the very next day, she opened what would become a full-time high school there.

Hoover also started a community college. He had met Stokely Carmichael, a protege of the Civil Rights movement who had a famous ideological split with Martin Luther King, Jr., over the notion of “black power.” Favoring integration, King felt that the slogan “black power” would spread the idea that the movement was about black domination instead of black equality.

By this time in the late 1960s, the civil rights movement had gained so much force that a lot of people in the industry were looking for ways to show that they were good corporate citizens. Bob Hoover of David Packard

But he understood that Carmichael’s ideas stemmed from frustration after watching urban black communities across the United States become entrapped by rampant housing discrimination, poorly funded schools and social exclusion from job networks. In his final book, King would write that, “the suburbs are white nooses around the black necks of the cities.”

Hoover recalls Carmichael asking him, “Why would you be so committed to turning over the minds of your children to people who have oppressed them for 400 years? We need to build our own institutions.”

Even so, they were building a college amid enormous hurdles. At the time, East Palo Alto’s unemployment rate was about twice the national average, 63 percent of the population was under the age of 25, and only half of the adults had a high school education.

When Hoover had problems fundraising, he turned to David Packard, the co-founder and CEO of Hewlett-Packard. They had been co-chairs of the local chapter of Common Cause, a political advocacy group pushing for transparency in government.

So much had changed in a decade.

“By this time in the late 1960s, the civil rights movement had gained so much force that a lot of people in the industry were looking for ways to show that they were good corporate citizens,” Hoover said of Packard.

Packard, a lifelong Republican running one of the Valley’s most iconic technology corporations, ended up filling out the initial round for Hoover’s Black Power college.

Packard’s commitment was real, Hoover said. HP and its black leaders, including Roy L. Clay, Sr., championed hiring from historically black colleges.

“He came to every single meeting,” Hoover said. “He brought in so many other CEOs into the organization and it created a lot of job situations for our community.”

Bob Hoover (left) in the early 1970s leading Nairobi College, which taught courses from physics to Swahili and was partially funded by Hewlett-Packard co-founder Dave Packard.

By 1969, Nairobi College offered 25 courses on everything from physics to black legal problems to Swahili. Classes were taught everywhere from people’s apartments to the teen center, and all students were required to complete four hours of daily community service in the schools, health and welfare centers.

A wave of Afro-centric institutions opened up across East Palo Alto. If they couldn’t find it, they were just going to build it themselves.

Yolanda Rhodes, a soprano who grew up in East Palo Alto, remembers seeing the children of the Shule Mandela school play around town. It was different from her upbringing, when she said she felt bombarded with messages and images that blacks were bad or worthless.

These kids were different.

“There was something very special about them,” she said. “They had a sense of internal power. They were charismatic and articulate. You’d see them and think who’s that? Oh, they’re from that Nobantu school.”

Nairobi

In 1968, younger East Palo Alto community members even ran a campaign to rename the city ‘Nairobi,’ reflecting its black ethnic make-up. Kenyatta and Uhuru were alternatives.

But the initiative failed because it split the community along age lines. Older African-Americans thought the name ‘Nairobi’ was too visibly associated with living in a ghetto. Had the voting age been lowered to 18 by that point, it might have passed.

Affirmative action

Getting African-Americans into universities was another battle. In 1960, the year after Hoover arrived, just two of Stanford’s freshmen were black.

One day in March 1968, four teachers from the East Palo Alto Day School took 50 children on a field trip to see an African art exhibit at Stanford.

A university-led review could not ascertain exactly what happened later, but a teacher testified that the children had been searched and forced to open their bags, making them feel as if they were being accused of shoplifting. Wilks fired off a letter to Stanford’s administration.

Two weeks later, Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated. At a campus memorial for King, Wilks, the East Palo Alto children, and a group of black Stanford students sat in the front rows.

“Not long after I had begun to speak, the entire population of the first several rows of the audience rose as one person,” recalled Richard Lyman, who was Stanford’s president at the time. “I thought they were about to walk out in protest, but they walked up onto the stage instead.”

One member of the group, Stanford student Frank Satterwhite, also known as Omowale Satterwhite, read a series of demands. One ask was that Stanford recruit minority students from the surrounding communities in East Palo Alto, East Menlo Park and Santa Clara County.

And so, affirmative action at Stanford was born.

Housing discrimination

But even if blacks started to find good, higher-paying tech jobs or get into universities in the late 1960s, housing discrimination still deeply impacted their ability to find homes. Ocie Tinsley, who moved to Santa Clara Valley to work in research and development for Lockheed Martin, recalls being stuck living in hotels for two months while his white co-workers were able to immediately find single-family homes.

African-Americans across both counties organized to get fair housing ordinances passed in city after city starting with Milpitas in 1954, then in San Jose and others.

California got its first statewide fair housing law passed in 1963 with the help of Northern California’s first black legislator William Byron Rumford. But it was soon overturned by a ballot initiative, which Ronald Reagan praised in his gubernatorial re-election campaign.

“If an individual wants to discriminate against Negroes or others in selling or renting his home, it is his right to do so,” Reagan said in a press release at the time.

Finally a week after King’s death in 1968, the federal government passed its own fair housing law.

The passage of these laws meant that by the time that scores of highly educated East and South Asian immigrants began to arrive in the Silicon Valley beginning in the 1970s and 1980s, they could live wherever they could afford it. This is even though San Francisco was home to the some of the country’s first racialized zoning laws, which limited the spread of Chinese-American run laundries and were later struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court.

By the time my mom and her father stepped off a Greyhound bus and set foot in Silicon Valley for the first time around 1980 as Vietnamese war refugees, no one could tell us where we could or couldn’t live.

No one could shunt us off to neighborhoods and schools that were arguably set up to fail.

Immigration

Moreover, it was the Civil Rights movement that helped to open the door to immigrants from outside Northern and Western European countries.

For about eighty years, immigration from mainland China had been all but shut off. Taiwan was limited to 100 visas per year.

But by the 1960s, the old immigration quotas, which were based on national origin and designed to maintain the U.S.’s existing racial composition, had become a “nearly intolerable” form of discrimination in former President John F. Kennedy’s words. After Kennedy was assassinated, his successor President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act and the Voting Rights Act less than two months apart.

The immigration law would change Silicon Valley forever. In 1960, Santa Clara County, which is home to Google and Apple, was 96.8 percent white.* By 2010, it was 32 percent Asian-American and 26.9 percent Latino or Hispanic.*

Under the new system, immigration policy would select immigrants on the basis of their skills or their existing family ties in the U.S. It kicked off a “brain drain” from the world’s most populous countries, India and China, which both had governments that were less than 20 years old at the time. A shaky sense of political stability combined with poor economic growth and disastrous projects like The Great Leap Forward encouraged the crème de la crème of these countries to seek better fortunes abroad.

Many of the most technically educated migrants favored by the new U.S. immigration policy ended up in Silicon Valley. Reforms and explosive economic growth have since tilted the balance back with the emergence of new tech hubs in Bangalore and Beijing.

But if the 1965 law had one effect on the Asian-American population, it had an entirely different impact on the Latino community.

Until 1965, Mexican migration had largely been channeled through a temporary worker initiative called the bracero program. The old approach was flawed; labor activists like Cesar Chavez, who lived for many years at the southern end of what is now Silicon Valley in San Jose, criticized it for allowing farm owners to take advantage of low-income migrants who worked under terrible conditions.

But the new system was also problematic. It put numerical caps on immigration flows from the Western hemisphere for the first time. These caps were far below what the realistic economic demand for labor would be, especially in lower-wage, lower-skilled segments of the workforce.

For example, in 1956, 65,000 Mexicans legally entered the United States as documented migrants while another 445,000 came as guest workers. By 1976, the guest worker program had been abolished and legal immigration from Mexico was capped at 20,000 people per year.

The economic prosperity of the 1960s that allowed the U.S. to have difficult conversations about race, war and gender gave way to a more uncertain environment with higher unemployment and inflation.

This, of course, led to large flows of undocumented immigrants, who were then vilified in the mainstream media for breaking the law and being a drain on public services. The border was then militarized, and the Border Patrol’s budget went from from $151 million in 1986 to $1.4 billion and 21,000 officers this past year.

Paradoxically, this led to the undocumented migrant population becoming more permanent because of the risks of getting caught going back and forth.

Silicon Valley loves a good immigrant’s tale. One-quarter of the region’s technology companies between 2006 and 2012 had at least one founder born abroad, according to the Kauffman Foundation.

But not all immigrants arrive in America equally.

1970s: Setbacks for desegregation and the emergence of “Silicon Valley”

In the 1970s, Silicon Valley finally earned its name after a weekly trade newspaper called Electronic News ran a series on all the semiconductor companies throughout the region. The founding of firms like Kleiner Perkins in 1972 made venture the engine of capital that would fuel successive generations of technology companies.

But East Palo Alto was still an island amid a growing plenty.

The legal victories around fair housing and school desegregation gave way to the more difficult reality of actually implementing these gains. The economic prosperity of the 1960s that allowed the U.S. to have difficult conversations about race, war and gender gave way to a more uncertain environment with higher unemployment and inflation.

In 1970, the Office for Civil Rights found that the school district covering East Palo Alto was in violation of desegregation laws. The district had three months to desegregate all six of its high schools or face the loss of federal funding.

In order to attract more white students, East Palo Alto’s high school, Ravenswood, added rock climbing, organic gardening and Hebrew classes. Initially, it was somewhat successful with roughly 400 more students joining in 1971. But the overall forces of white flight and declining enrollment were too powerful, so the district shut down the school in 1975. The same year, the two Nairobi schools got fire bombed and burned down; investigators found two Molotov cocktails around the buildings.

Another African-American mother named Margaret Tinsley, who, like Wilks, was worried about low-quality schools, sued to get children into better-funded neighboring districts. The case took a decade to settle, but it eventually won the right for 166 East Palo Alto students to get into outside schools using a lottery. Today, East Palo Alto’s high school students get bussed to some 18 different schools outside the city.

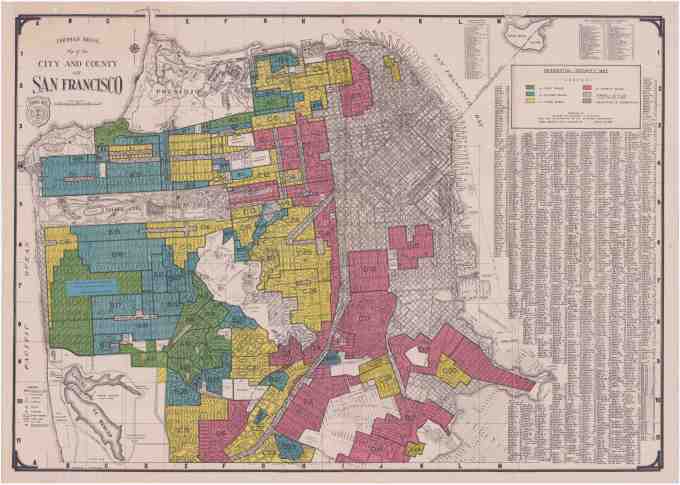

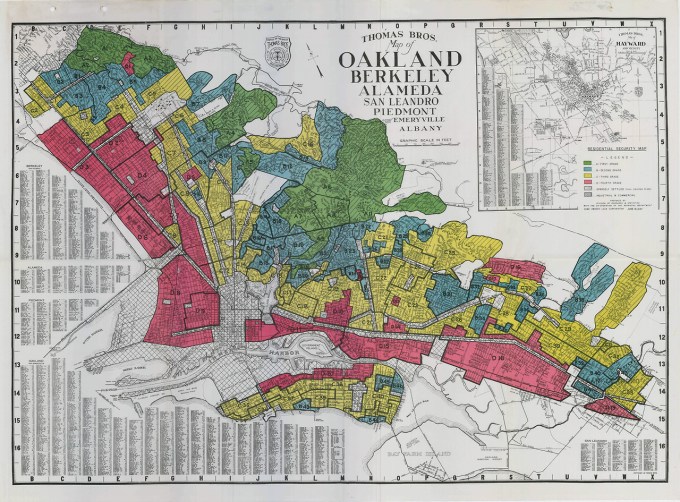

Undoing de facto housing segregation turned out to be much harder than simply changing the laws. For several decades, the Federal Housing Administration and private banks engaged in a practice of redlining, where they would back mortgage lending to certain neighborhoods that happened to be predominantly white and excluded others that housed minorities. You can find redlining maps of cities across the entire country including San Francisco and Oakland.

Old redlining maps from the 1930s of San Francisco and Oakland. Areas marked red were considered the most risky for mortgage support. In effect, redlining meant that these neighborhoods, often populated by minorities, could not secure comparable or sometimes any access to mortgages or capital. That in turn capped property values and revenues for public services.

The availability of capital drove differentials in property values between neighboring communities, making it harder to jump from one to the next. Because homeownership was the primary way that U.S. federal government encouraged Americans to protect and grow their wealth, this practice basically left out entire groups of people from capital accumulation. On top of discriminatory job practices from decades ago, it has lingering effects to this day; last year, the median net worth of a white household in the United States was $141,900, compared to $11,000 for blacks and $13,700 for Hispanics.

The federal government tried to put an end to redlining through the Community Reinvestment Act in 1977. It had immediate effects. While the median East Palo Alto home price rose sluggishly compared to its neighbors from $18,000 to $23,000 from 1970 to 1976, prices doubled to $46,000 by 1979 with the new ban on redlining.

But it was too late. Segregation had hardened into neighborhood price differentials, and only the most educated and upwardly mobile blacks could move out into the rest of the Silicon Valley suburbs.

Integration would turn out to be a double-edged sword.

“Before blacks could live anywhere else outside East Palo Alto and Belle Haven [in Menlo Park], everybody lived in the same community,” Hoover said. “But once integration came, the middle-class and professionals left. So you were left with a low-income, poorly educated community with opportunities only for very low-wage jobs. Not only are your role models and economic engine gone, your leadership is too.”

When Hoover was a child, he would go to black barbershops frequented by black doctors, lawyers, dentists and teachers from the community. He would overhear their conversations and imagine himself as one of them some day. But for East Palo Alto children of the 1980s, many of the middle and upper-class black families would have left by that time.

California also had its own dynamics.

Beginning in the late 1960s, a wave of growth-control movements sprouted throughout the entire San Francisco Bay Area as homeowners pushed back on apartment and multi-unit housing construction. Cities enacted rules that limited the number of houses that could be built per year and put protections on undeveloped land. In addition, the California Supreme Court issued rulings that said that municipalities didn’t have to compensate property owners for downzoning their land and required environmental reviews for any sizable development.

Ostensibly, these growth controls were about environmentalism, but they also served to protect property values and prevent suburban governments from having to service lower-income residents. Today, Palo Alto has a median home price of $2 million, the highest jobs-to-housing ratio in all of Silicon Valley with three jobs for every housing unit, and 42 percent of its land under conservation protections against development.

One result of all this anti-development legislation was that the behavior of coastal California home prices started deviating from the rest of the United States in the 1970s. California homes started off the decade priced at roughly 30 percent more than the rest of the country. By 1980, they were nearly double. It was an enormous sea change from just 20 years before, when the state issued one out of every five housing permits in the country.

With property prices soaring, the state’s voters rebelled by passing Proposition 13, which slashed property tax revenue by more than 50 percent the following year.

Beginning in the late 1960s, a wave of growth-control movements sprouted throughout the entire San Francisco Bay Area as homeowners pushed back on apartment and multi-unit housing construction.

Because homeowners could now lock in low property tax rates under Proposition 13, the initiative insulated them from the negative tax consequences of not building enough housing. There are scores of empty houses in West Oakland, another heavily redlined and African-American neighborhood just one BART stop from San Francisco, because it’s inexpensive to leave the houses vacant and ride the property price appreciation on a flip instead of redeveloping the land at a higher tax assessment.

Proposition 13 also made it harder to move, reducing turnover for new families looking for housing.

“Real-estate inflation is the tax that one portion of society – older, more affluent homeowners and corporate landowners in coastal areas – levies on the rest of society, especially younger, less affluent families,” Mike Davis once wrote in “City of Quartz,” a spatial history of Los Angeles.

Indeed, Palo Alto’s population has aged rapidly, going from a median of 29.5 in 1970 to 41.9 years in 2010. Many of the “lower-income” households in nearby Atherton, which is the most expensive ZIP code in the country this year, are house-rich but cash-poor seniors living in multi-million dollar properties.

One of the other problems with Proposition 13 was that it widened tax revenue differentials between urban and suburban areas and wealthier and lower-income communities.

If the alienation and disaffection of California’s urban ghettos produced the strident voice of leaders like Oakland Black Panthers founder Huey P. Newton, California suburbs would respond with Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, who refined the art of racially coded appeals veiled in the language of individual rights, tax cuts and minimal government.

Since public school districts at that time received half their funding from property taxes, and schools in wealthier neighborhoods could get around the cuts through PTA fundraising, Proposition 13 gutted funding for urban school districts.

In the wake of Proposition 13, East Palo Alto would finally incorporate as its own city after a two-decades-long struggle in 1983. There were bitter debates over whether the community would generate enough tax revenue to support services like law enforcement, which had previously been provided by the county government. Wilks controversially opposed incorporation and even filed suit with the help of Pete McCloskey, a U.S. Congressman who founded the storied Silicon Valley law firm that had just represented Apple in its IPO, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati.

One concession made to win support was to institute rent control, making East Palo Alto the only city between San Francisco and San Jose to have such an ordinance. Rent control is almost universally decried by economists because it can allocate units inefficiently. But in the specific case of East Palo Alto, it has to be understood as a political response to policies that systematically denied African-Americans pathways into homeownership for decades.

Now, a newly incorporated city without its own high school and little in tax revenues, East Palo Alto was about to enter its most difficult decade yet.

Mid-1980s to early 1990s: Descent

Before he left the U.S. for West Africa out of fear that he would be assassinated like King and Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael left Hoover with an ominous message.

“Our communities are going to get flooded with drugs and we’re going to eat ourselves up from the inside,” he said.

Growing up in the 1980s, it often feels like certain ideas or communities are a permanent part of the urban landscape. They aren’t. Homelessness emerged as a major political issue in San Francisco only in the early 1980s.

Likewise, the archetype of the black drug dealer or the “gang-infested” ghetto surfaced around the same time. With its position right off the 101, East Palo Alto would become the area’s main drug hub at a time when the industry’s iconic leaders like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs were duking it out in the PC and Mac wars of the early 1980s.

Back in the 1970s, cocaine was considered the “Champagne of drugs” at a cost north of $2,500 an ounce and up. It spread among the elite from Wall Street to Hollywood, but a new technique involving cooking it with baking soda and water made the drug far more affordable in the form of smokable rocks, or crack cocaine. That introduced cocaine to a whole new, lower-income audience and made it far more addictive in short bursts.

Crack cocaine devastated urban black communities at a time when they were at their most vulnerable. The residual isolation of housing segregation combined with the loss of manufacturing jobs to both the suburbs and overseas countries meant that there were few alternative job or economic opportunities in these neighborhoods. Poor schools meant that kids were ill-prepared for an increasingly limited blue-collar job market. Instead, Hoover said kids could make the equivalent of $500 a day selling crack or heroin.

One by one, he watched the kids he had taught in Little League, the Nairobi schools and college fall away.

“Drugs just destroyed our children,” Hoover said. “We had a vision for this community in the 1960s and 70s. When the drugs came, it stopped it dead in its tracks.”

Between 1984 and 1994, the homicide rate for black males aged 14 to 17 would double nationally. The gains made over the previous two decades in closing the black-white achievement gap in high school graduation rates reversed.

At the same time, the Reagan administration cut commitments to public and subsidized affordable housing from the peak of the 1970s. Today, the federal government forgoes roughly $70 billion in tax revenue each year through the mortgage interest tax deduction even though three-fourths of its benefits accrue to the top income quintile in the country.

Meanwhile, the annual Housing and Urban Development budget, which is supposed to support low-income communities is roughly two-thirds of that at $47 billion. The decline in federal funding for housing is partly why cities like San Francisco are having such a tough time finding funding for affordable housing development and have to “tax” new housing construction through inclusionary requirements and fees.

These cuts came at a time when cities were grappling with revenue loss from “white flight,” the emergence of drugs like heroin and crack cocaine, de-institutionalization of mental health facilities and the return of veterans from Vietnam War. It was like a perfect storm for urban communities in the Bay Area.

“In the 1980s, everybody was struggling and barely making it. Then suddenly there were guys in cars with all this capacity to get the things you couldn’t have,” said Heather Starnes, who moved to East Palo Alto in the late 1980s and runs a nonprofit called Live in Peace, which teaches music, college prep and coding through a new program called StreetCode Academy. “It starts out real innocent and then suddenly, your mom’s on it.”

David Lewis, after whom Hoover’s prisoner re-entry program is named, came into drug dealing after teachers wrote him off because of his dyslexia. With a father who was an alcoholic, he had few role models and dropped out. He ended up in jail for 17 years for various convictions of drug use and robbery before beating his habit and starting a nationally renowned drug rehabilitation program in East Palo Alto.

“I considered myself at 15 to have a full-blown drug addiction, but I still had this burning desire to succeed,” he said in interviews before he was murdered in 2010. “And the people that I saw succeeding, they weren’t people who were going to school. They were people involved in criminal activity.”

Gangs came into the picture in East Palo Alto around the mid-1980s. A crude analogy would be to think of it like M&A; gangs would roll up the drug business in East Palo Alto the way that any new market gives way to consolidation as it matures. The gangs protected rights to dealing spots that ensured a constant flow of revenue.

The federal government responded to media reports of the emerging “crack epidemic” by passing the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which penalized crack cocaine 100 times more harshly than regular cocaine. For possession of five grams of crack cocaine, there was a minimum five-year sentence. A person would have to carry 500 grams of regular cocaine to earn the same ruling.

In hindsight, academics and activists, such as “The New Jim Crow” author Michelle Alexander, say that this paved the way for a criminal justice system that unjustly sweeps minorities into the prison system, making it difficult for them to recover or find employment later. Today, 59 percent of federal and state prisoners are either black or Latino.

The situation kept escalating until its culmination in 1992 when there were 42 murders in a city of fewer than 24,000 people. About 40 percent of the deaths were from outsiders going into the community to buy drugs.

You couldn’t have had a starker contrast between the city and the rest of Silicon Valley, which was on the verge of untold wealth with the arrival of the commercial Internet.

East Palo Alto was branded the “Murder Capital” of the U.S.A.

1990s to 2000s: Recovery and the Dot-Com Boom

The crisis forced everyone into action.

When bullet casings started showing up in the backyards of Menlo Park and Palo Alto, the neighboring communities, some of which had resisted for decades to keep East Palo Alto children out of their better-funded schools, donated police officers to the city’s understaffed department.

The three mayors of East Palo Alto, Menlo Park and Palo Alto struck up a partnership and helped form the anti-drug ‘RED Team’ or Regional Enforcement Detail. County, state and federal officials also became involved. All in all, the law enforcement coalition would make more than 1,000 arrests over the next two years.

East Palo Alto residents also took matters into their own hands. Armed with just two-way radios, Hoover and other activists started monitoring street corners, taking down license plates of drug buyers and reporting drug sales to the police. They’d go to a single street corner and patrol it every morning and night for six months.

“We became like the police ourselves,” Hoover said. “I went out on the streets. My wife was always afraid that someone would kill me. But the thing is, I had known all of these kids selling drugs since they were little children.”

He’d sit and talk with them. “Our position was always — what you’re doing is destroying this community and it has to stop. If you are willing to stop, we will help you find something else to do.”

Homicides fell by 86 percent the following year.

Silicon Valley’s most prominent companies and families started making charitable commitments. Some of it enabled handfuls of children to make it out into four-year universities.

These programs only take the kids that they’re pretty sure are going to be successful. Bob Hoover

In 1995, Laurene Powell Jobs, Steve Jobs’ widow, co-founded College Track after realizing that many of the East Palo Alto children had no idea about how to apply or prepare for college even if they had ambitions to be the first in their families to get there. Sharifa Wilson, who was mayor of East Palo Alto in the early 1990s, says that between 400 and 500 students have since completed college since the program started. “Laurene is thoroughly committed to equity,” Wilson said. “I have a tremendous amount of respect for her.”

Some of the charity was opportunistic.

In 2000, Carly Fiorina, then CEO of HP, was concerned that the company wasn’t getting enough publicity for its philanthropy. The Friday before then President Bill Clinton was supposed to visit a new technology center in East Palo Alto called Plugged In, a communications manager for the company dialed up its executive director Magda A. Escobar.

They asked Escobar to call the San Jose Mercury News to play up how much the company had given to the center over the years after a story had incorrectly attributed a donation to Sun Microsystems instead of HP.

While Escobar was grateful for the call, if publicity was what HP wanted, it would need an attention-grabbing figure. She suggested $1 million toward a permanent home for Plugged In would get HP on the front pages. The following Monday with Jesse Jackson, Clinton and Escobar also onstage, Fiorina got the headlines she wanted.

However, unbeknownst to everyone at the time, the NASDAQ and S&P 500 had peaked a few weeks earlier. The dot-com bubble would collapse. Startups and jobs across the region would get obliterated.

Fiorina’s donation ended up being a life raft for Plugged In. But the overall $5 million commitment that the company made to the city, which was the size of a standard Series A round, became a source of political stress.

The money enabled Plugged In to keep going for years after similar efforts around the country failed for lack of funds. However, Plugged In eventually closed doors in 2008 after it merged with another national non-profit with the intent to use the rest of its $1 million nest egg for continued growth. Like a startup acquisition that went nowhere, it got shut down. It would take years until the emergence of StreetCode Academy for a new community technology center to emerge again in East Palo Alto.

While the new charity efforts of the 1990s and 2000s helped, they also introduced complications.

“Charity is a form of power,” Escobar said.

Kids, for example, were easy to fundraise for.

But parents, which are certainly at least half of the equation, were not.

“It’s the missionary mentality,” Hoover said. “We have to send the saviors from across the freeway. These programs only take the kids that they’re pretty sure are going to be successful. You’re taking the top 5 percent, so what happens to the other 95 percent? They won’t touch the kids that really need help.”

In 1995, two days after Netscape debuted to a $2.9 billion market cap on public markets, Jerry Bruckheimer would release Dangerous Minds, a Michelle Pfeiffer vehicle about a white former Marine who goes into school system to reform East Palo Alto high school students.

For the children from the most recent generation in East Palo Alto, there are just extraordinarily difficult emotional and financial hurdles.

“The kids that were basically born from 1986 onward have a whole different reality than any other generation of African-Americans prior to them,” Starnes said. “It is extremely hard. Our kids don’t know life without black people being portrayed on TV as drug dealers or prisoners.”

Starnes ended up helping to raise three children whose parents weren’t around. One was born to a 12-year-old mother. Another grew up to be a sheriff in Alabama, but still grapples with forming close emotional relationships.

“Having relationships with crack addicts is complicated. They are a shell of their former selves — all the beauty and brilliance begins to be defined by addiction. People who would have died for you are overtaken. They become people you don’t recognize,” Starnes said. She remembers that people with addicted relatives had to take precautions like padlocking their refrigerators, doors and cabinets to prevent stealing for the addiction.

The third child was a baby named Angelika.

One weekend when she was six years old, Angelika went over to spend the night with the rest of her family. Starnes was close with pretty much all of them; three of them were like godchildren.

At 6 a.m. the following morning, the area in front of the house’s only door inexplicably burst into flames.

Thirteen people were sleeping in it at the time. Four of them were able to escape, but the other nine were trapped behind anti-burglar bars bolted onto the house’s windows.

Anjelika and Starnes’ other godchildren, Donta’ and Ja’meace’, died. The fire department ruled that it was an arson based on the flammable liquid they found all over the carport. But after nearly two decades, a $50,000 reward and more than a hundred interviews later, they were never able to identify a perpetrator.

Starnes left East Palo Alto, thinking it would be for good.

“People could never fathom the weight that is carried in a community like this,” she said. “Poverty is exhausting, it is hard enough to live, raise a family and then you add all of this trauma. Our children. They’re just full.”

Many other families made the same choice. With housing prices reaching record levels during the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, many black families had decided that they had had enough. They sold at a profit and left for the South or suburbs somewhere farther out.

East Palo Alto transitioned into being a majority Latino community. The cheaper housing prices and abundance of low-wage jobs in Silicon Valley attracted immigrants from Mexico and Central America.

Dreams Awake from Sub64Films on Vimeo.

Doroteo Garcia was one of them. A native of Oaxaca, he was making the equivalent of about $40 every two weeks selling auto and electrical parts back in Mexico. When he heard you could make $5.75 per hour, which was the minimum wage in the mid-1990s, it sounded like a lot.

In 1996, he left his wife and two sons behind and headed north. Today, he is a janitor at Stanford University, making $30,000 a year. He pays $1,100 a month for a one-bedroom rent-controlled apartment that he shared with one of his sons until he went off to college in Seattle. He still sends $100 home every month.

“I knew nothing about Silicon Valley,” Garcia said. “People told me how much you could make, but nobody told me how much you’d have to pay.”

Even with East Palo Alto’s newfound media attention and some charitable support, the 1990s weren’t a particularly hospitable time for minorities in the state of California; voters tightened access for underrepresented minorities to university admissions and toughened penalties in the state’s criminal justice system.

In 1993, Facebook’s first angel investor Peter Thiel and David Sacks, who would eventually sell Yammer to Microsoft for $1.2 billion, wrote a piece entitled “The Case Against Affirmative Action” in the Stanford alumni magazine:

“….racism is not everywhere, and there is very little at a place like Stanford. Certainly, no one has accused Stanford’s admissions officers of being racist, so perhaps the real problem with affirmative action is that we are pretending to solve a problem that no longer exists.”

Both immigrants, Thiel would have arrived in the United States sometime around 1968, the year when de jure housing segregation ended, and Sacks was born the son of an endocrinologist in Cape Town, South Africa. (Sacks declined to comment for this story. But a recent article in The New York Times on women explains how his thinking has evolved over the past 20 years.)

A few years later, California voters would pass Proposition 209, which ended racial and gender preferences in hiring and admissions for public institutions. Today, African-American students make up a little bit more than 130 students out of every 4,500-person freshman class enrolled at UC Berkeley.

Around the same time, California voters also passed a Three Strikes Law, which would give prisoners 25 years to a life sentence after three felonies, and Proposition 187, which cut off health care, education and social services to undocumented immigrants.

While Proposition 187 got stalled, the Three Strikes Law has contributed to the state’s prison system ballooning by more than 750 percent since the 1970s. Today, California’s prisons hold nearly twice as many inmates as they were designed for.

Today: Gentrification

Now that East Palo Alto has brought its crime from the high-water mark of the early 1990s, the irony is that the community is now prone to gentrification.

East Palo Alto represents the last piece of land that is substantially more affordable than every community around it. Its median home price is $534,000, compared to $2.1 million in Palo Alto, $4.6 million in Atherton, $1.6 million in Menlo Park and $1.1 million in Mountain View.

In the mid-2000s housing boom, real estate pressures came to a head. Lenders started going door-to-door in East Palo Alto neighborhoods in an attempt to get homeowners to refinance their homes or to buy property using subprime mortgages.

It was strange for longtime residents who remembered the days when African-Americans had virtually no access to credit. Now banks could pass off the lending risks to someone else by securitizing these loans.

“There was this surge of predatory lending with all of these subprime loans that were pressed upon the community,” said Carol Lamont, who has worked in Bay Area affordable housing for more than two decades and managed East Palo Alto’s rent control ordinance until this year.

Twenty-two hundred of the 6,600 single-family homes in the city went into foreclosure, according to AbleWorks, an East Palo Alto nonprofit that was able to salvage about one-third of its foreclosure cases.

Tameeka Bennett, one of the city’s most prominent young activists and community organizers, saw her parents lose their home of more than 20 years after taking a refinancing deal from the Bank of America. She didn’t know what they had done until it was too late.

“They didn’t understand that this would take the whole 30-year process and reset it,” said Bennett, who is now commuting more than two hours a day from Oakland to lead the community she once grew up in. “The whole thing didn’t work out well for them.”

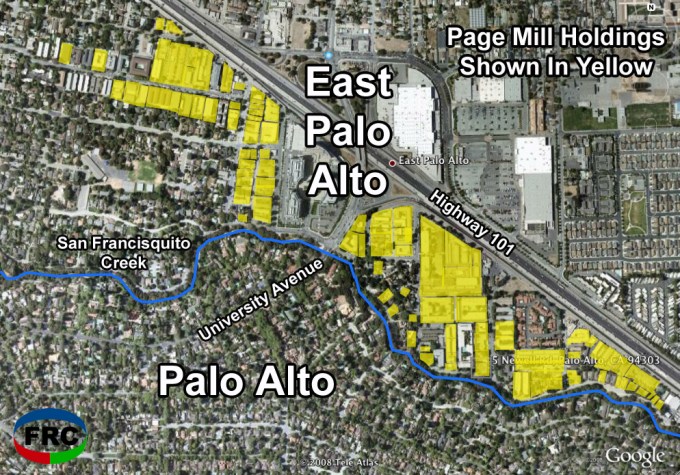

Around the same time, a Silicon Valley real estate developer named David Taran started buying up more than 70 parcels in a strip along the highway separating Palo Alto and East Palo Alto. It contained about 1,800 mostly rent-controlled units, or roughly half of the city’s rental housing stock.

He then tried to raise rents by hundreds of dollars through a loophole in the city’s rent-control ordinance.

But the 2008 financial crash caused Taran’s Page Mill Properties to default on a $250 million loan. Some of the entity’s investors sued, calling his plan “morally offensive” and arguing that Taran had misrepresented the way Page Mill would use the city’s rent control laws. CalPERS lost $100 million on the deal. Taran could not be reached for comment.

East Palo Alto tenants thought they had won a reprieve.

Instead, the properties got scooped up by an even bigger entity, Sam Zell’s Equity Residential, one of the largest real estate investment trusts in the country. Over the summer, Equity Residential was sending roughly 300 notices a month to tenants in its 1,800 units to pay rent on the first day of the month in a bold tactic to tally late payments toward evictions, according to Daniel Saver, a lawyer at Community Legal Services.

“A lot of people are just terrified that they’re going to get evicted,” said Saver, who recently moved to East Palo Alto as a recent Harvard Law School grad. “These are corporate entities that understand how non-payment works. They’re very aggressive and they’re not creating exceptions for moms who are one emergency away from homelessness or eviction.”

Community Legal Services has since filed a class action lawsuit against Equity Residential, saying that its late charges are “excessive” and “unlawful.”

Other property buyers have been scouting for homes to flip to tech workers. Rhodes remembers meeting a friend of a friend in a Palo Alto bar who worked in real estate. He offered to pay her $500 to drive him around the city and point out properties to buy and flip.

“Why would want I want to drive that guy around East Palo Alto?” she said. “It would be like I’m his chauffeur. I would have to listen to all his antics and give him information that he would use to exploit the city.”

Unusual times call for unusual measures. Starnes, who returned to East Palo Alto after graduate school and working in Oakland’s middle schools, has started compiling a list of all the elderly black homeowners in the city to try and convince them not to sell to outsiders.

Saver says that East Palo Alto needs a minimum of 2,000 permanently affordable units. He says that unlike Palo Alto and Menlo Park, residents he has talked to are open to redevelopment or upzoning, as long as it doesn’t displace them.

Assuming a $200,000 subsidy per unit, that could be a $400 million effort in exchange for denser zoning that would allow workforce housing. It’s arguable that such a deal could be in Facebook or Google’s interest if they need housing for talent right near their campuses.

In spite of these pressures, parts of East Palo Alto are thriving.

Starnes, along with Stanford computer science students Shadi Barhoumi and Rafael Cosman and alums Olatunde Sobomehin and Justin Phipps, have transformed the campus of a former remedial school into a programming academy.

They teach everything from beat-boxing to Arduino and mobile app development. At a kick-off event last month, musicians were rapping onstage about APIs and a group of girls had created a mobile app for reporting blight to the city government.

I’ve been back several times. It’s the real deal. There are kids carpooling in from as far as San Ramon to hack on hardware, play basketball and learn mixed martial arts.

Barhoumi isn’t any kind of hyper-privileged Stanford kid, either. He was raised in the nearby suburb of San Mateo. His mom is an ESL teacher and his father, a former systems test engineer, picked up Uber driving seven days a week after being unemployed for years.

He decided not to apply for lucrative internships to build the StreetCode Academy while Cosman confessed his grades were sort of suffering with all the hours they were putting into it. They funded a summer coding camp with money from donors like Mitch Kapor, Jeff Dean from Google and Jason Green from Emergence Capital.

At a recent hackathon, kids made products to share football playbooks or raise funds for their soccer teams. At a CodeCamp graduation over the summer, David Chatman, who grew up in East Palo Alto and had to drop out of college to help his mom make ends meet, burst into tears after pitching a site he built to showcase profiles of young East Palo Alto students.

“You have no idea how I wanted this so badly,” he said, hugging Barhoumi.

Shadi Barhoumi is a Stanford computer science major who helps run the Streetcode Academy and teaches programming to East Palo Alto students.

The proximity to Stanford and Silicon Valley has had its benefits over living in other low-income communities that are farther out.

Two years after Facebook relocated its headquarters from Palo Alto to an old Sun Microsystems campus on East Palo Alto’s border in Menlo Park, Zuckerberg made a $1 billion commitment to the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, of which $120 million will go to local schools. So far, a little over $1 million has been disbursed for iPads and Chromebooks to East Palo Alto’s Ravenswood District, while another $2.5 million has gone to schools in San Francisco and Redwood City. Every summer, the company takes in local East Palo Alto high school students for internships.

Then earlier this year, Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan gave $5 million to a local health center. The pair have tried to be much more hands-on with their local commitments after learning from a $100 million philanthropic donation to Newark’s school system. That gift was skewered in The New Yorker for being spent on consultants instead of classrooms.

Last year, Zuckerberg taught a 10-week course on entrepreneurship to East Palo Alto middle-school students, who created business plans and then sold their products on the company’s campus. He continues to personally mentor four of those students, who are now sophomores in high school. Meanwhile, chief product officer Chris Cox has played in an East Palo Alto reggae band for about a decade and has been deeply involved in supporting several city non-profits.

Still, there’s this disconnect between the Valley’s charitable efforts and acknowledging how the structure of the region’s housing, job and educational markets create these disparities in the first place.

“If you’re fighting for crumbs, you’re never going to ask for a slice of bread,” Escobar said.

Facebook is a major charitable force in East Palo Alto that supports several dozen non-profits. But its presence may also eventually price out the community it intends to help.

Similarly, the foundation of Google co-founder Sergey Brin and Anne Wojcicki underwrites the computer science and engineering curriculum at Eastside College Preparatory, a private East Palo Alto high school that has taken in about 300 local students, most of whom are black and Latino and will be the first in their families to go to college.

But Google, the company, uses low-wage labor in East Palo Alto for Google Shopping Express.

“This is the lowest I’ve ever gotten paid,” said Lerisa Puckett, who grew up in East Palo Alto and took a delivery job from 5:30 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. after seeing others in the neighborhood driving the white-and-blue Google Shopping Express cars around.

A mom of three who used to be a special education teacher, she had taken five years out of the workforce to raise them. One of her kids just left for college in Texas. Another is on scholarship at a private high school in Portola Valley while a third is in a public school in Santa Clara.

Puckett, who lives in a low-income housing development in Santa Clara, regularly visits East Palo Alto to see her 81-year-old grandfather, who still drives up five days a week to San Francisco to work as a janitor in China Basin, which houses Dropbox’s headquarters.

“I’d love to live here, but this has become a gold mine,” Puckett said. “It’s in the middle of everything. It’s in the middle of San Francisco, San Jose and it’s right here at the Dumbarton bridge.”

It’s not as if this is new. In 1970, half of East Palo Alto’s workers were in blue collar, clerical or cleaning jobs.

The same report about East Palo Alto from 1968 that I quoted above read:

“The high-technology mid-peninsula represents in many ways, the kind of regional economic development that will befall many other areas in the nation in the years to come. In these growth cases, aggregates of low income, minority families will first provide low status service and other occupational categories — and quickly form poverty pockets or social problem areas if new patterns for integrating into mainstream living at a fast pace are not provided.”

It was something that King echoed at the end of his life when he tried to expand the Civil Rights movement into a broader movement around economic injustice and poverty. He argued that poor living standards for blacks weren’t simply about neglect or any kind of rationalization that one could make about family structure or education:

They are a structural part of the economic system in the United States. Certain industries and enterprises are based upon a supply of low-paid, under-skilled and immobile non-white labor. Hand-assembly factories, hospitals, service industries, housework, agricultural operations using itinerant labor would suffer economic trauma, if not disaster, with a rise in wage scales.”

And now, models like this are firmly entrenched within the most prominent startup successes of the last five years. Ten years ago, the industry’s leading growth-stage companies were pure software plays like Google and Facebook that compressed access to information for everyone. But online-to-offline models raise entirely new questions about equity.

None of the companies relying on independent contractors — Uber, Lyft, Homejoy, TaskRabbit, Google Shopping Express, Postmates, DoorDash, SpoonRocket, Washio, Handy and so on — have released the racial make-up of both their permanent workforces and their contractor bases.

To do so would be to open the Pandora’s box of questions about the extent to which these companies align with or even amplify pre-existing racial and socioeconomic inequities. Based on the tech companies that have released diversity data so far, it’s likely that you have a small base of full-time employees with job security and equity that are primarily white and Asian, and then a substantially larger and more diverse base of contractors that have neither.

Can Silicon Valley Really Save East Palo Alto While Devouring It?

In the end, there’s not a lot of time.

“In 15 years — maybe quicker than that — this is probably going to be a mostly white and Asian community,” Hoover said. “All I can do is keep running my little golf program and trying to build something that will increase the graduation rate of our kids from high school and keep them from going to prison. They are mostly Latino kids now, but they’re still my community.”

Home prices have more than doubled since the bottom in 2012, and there’s an informal, internal message board inside Facebook where people have discussed the merits and disadvantages of living in different parts of East Palo Alto, employees have told me. Many Facebook employees who joined after the company’s IPO cannot afford the multi-million-dollar home prices in neighboring cities.

Meanwhile, Palo Alto is one of the few cities that elected an anti-growth council this past fall, while nearby cities like Mountain View, where Google is headquartered, finally elected pro-housing leadership.

During the summer, a group of Palantir employees even showed up to council meetings to beg for more housing. They, along with other younger tech workers and retiring baby-boomers, formed a group called Palo Alto Forward to vouch for more housing and transportation options.

The reaction? You can get a flavor of it in the hundreds of comments here:

I’d love to see all of these young, pro-growth residents choose a place to make their own. Milpitas? East Palo Alto? Alviso? All places that would truly appreciate your innovation, education, and desire to develop the community.

Others still oppose the desegregation settlement from the 1980s that won a small number of students, including East Palo Alto’s current mayor Laura Martinez, the right to attend Palo Alto’s much vaunted school system. You can hear echoes of what Gertrude Wilks overheard in the PTA a generation earlier about minority parents not valuing education:

Our children don’t need [the Tinsley desegregation program] to experience diversity. There are plenty of Asian, European, and Hispanic immigrants in and around Palo Alto and they are hard-working adults. If anything, our students learn negative stereotypes by having Tinsley students in our schools because most of the Tinsley students are not at the same academic levels as Palo Alto students unless they have parents who help them at home and prioritize academics, most of whom do not.

Over the summer, I spoke with Gary Lauder, a venture investor who was the main financial backer behind a slow-growth initiative that would have capped development in downtown Menlo Park until it was defeated in November.

“I don’t object to adding stuff or having the place becoming more built up,” he said. “I just think that there needs to be greater emphasis on transportation infrastructure.”

He then directed me to a TED Talk he gave about a new traffic sign he invented.

It’s this chicken-and-egg logic that’s often used to stall projects, instead of pushing for a new regional vision that befits a place housing one of the most ambitious industries in the world.

“There’s this model of Palo Alto that people remember, envision and glorify as this sleepy little town where people could quietly raise a family and get around — this bucolic suburban lifestyle from 35 years ago,” said Elaine Uang, one of the creators of Palo Alto Forward. “With a huge demand to live and work in Palo Alto over the last 20 years, I’m not sure our city has been like that for awhile.”

What happened to East Palo Alto isn’t that unique. It happened to black communities across the entire country over the 20th century — New York City, Los Angeles, Detroit, Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia.

Instead of grappling with the reality that the Bay Area’s mid-20th century infrastructure and single-family home design are no longer adequate for the sheer size of the tech industry today, many of the original Silicon Valley suburbs like Palo Alto, Atherton, Menlo Park and Los Altos seem content to ride record home prices and make other communities in San Francisco and Oakland bear the cost of their now anachronistic land-use choices.

You have to ask what the end game is here — when 25 percent of Palo Alto homes are sold to overseas buyers as investments while the mainland Chinese property market tanks, when Palo Alto schools are known for their suicide rates as much as their academics, when the city that gave birth to the technology industry now can’t even house startups because of its sky-high commercial rents, when Latino and black communities are being wiped from the Western side of the San Francisco Bay Area and Oakland out into the exurbs of the East only to be called back by smartphone to deliver laundry or drive people around.

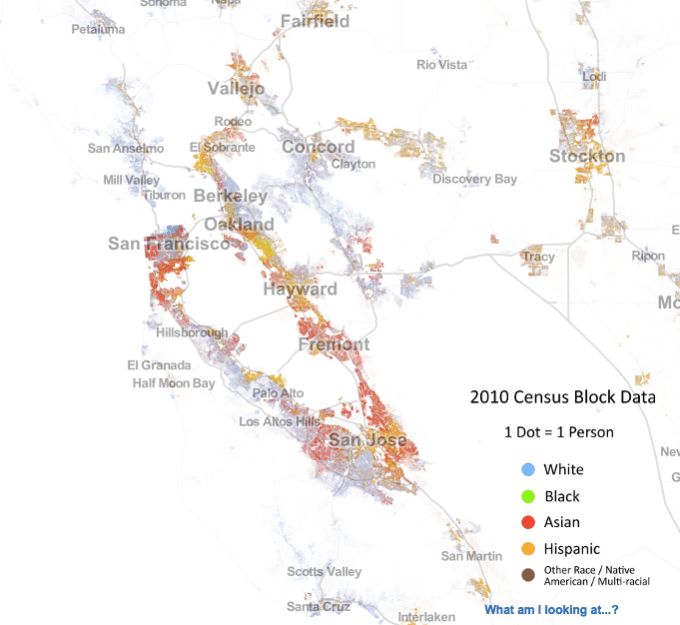

The San Francisco Bay Area remains residentially segregated with a primarily white and Asian western half of the Bay, while Latino and black communities live in the south and the East.

Kimberley Johnson, an urban studies professor at Barnard-Columbia who is writing a book comparing black communities in Oakland and Newark, N.J., wonders if the most economically successful American cities are belatedly reverting to the European banlieue model, with an urban core of wealth surrounded by a broad ring of poverty.

“As these populations are dispersed to the outer Bay Area, they are becoming fragmented and the political voice that used to occur is no longer there,” she said. “Lower-income communities are being displaced to Antioch and Pittsburg on the metropolitan fringe where there is a lack of public services like hospitals. These are privatized suburban spaces that weren’t designed to cater to the needs of lower-income populations.”

In urban governments, we sit around one table — the poor, the rich, the black, white, Latino and Asian. While you can’t romanticize the conditions of the inner cities 20 years ago, the larger political body of an urban government gives minorities the power to operate as a bloc and wrest resources or capital from a larger pool. The conversations San Francisco and Oakland have had over the last year have been hard, awkward and definitely far from perfect. But the point is that we have them.

Suburbs, in contrast, draw lines as they see fit and operate obliviously to the impacts they have on surrounding communities, which are often segmented by race and class. They can get cut out the way that East Palo Alto got cut out of Silicon Valley more than 50 years ago and left on the other side of the highway.

What happened to East Palo Alto isn’t that unique. It happened to black communities across the entire country. Residential segregation has been deeply corrosive to American society; it is the font from which economic and educational disparities and misguided criminal justice policies have arisen. To repeat it in the opposite direction with low-income communities surrounding an inner urban core of privilege would be a mistake.

It’s also a huge reason contributing to why there are so few minorities in the tech industry.

Silicon Valley loves to celebrate exceptional black and Latino entrepreneurs like Walker & Company Brands’ Tristan Walker — as it should. But it fails to see the structural problems that make these people the exceptions. Even when it happens right on our doorstep.

You can’t point at people and call that progress. African-Americans have been part of the technology industry for decades. There were two black members of the Homebrew Computer Club, which led Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to creating Apple. One of them, Gerald A. Lawson, created home video game consoles with interchangeable cartridges and even declined to hire Wozniak for a job at Fairchild Semiconductor. If Silicon Valley had started from a residentially integrated place, there probably would have been many more people like him.

Since the dot-com boom, it’s not clear if the industry has improved. In fact, it might even be getting worse. A San Francisco Chronicle investigative story into the make-up of 33 Silicon Valley tech companies from 1998 showed that they were 4 percent black and 7 percent Latino. Last year, Google’s workforce was 2 percent black and 3 percent Latino while Facebook was 2 percent black and 4 percent Latino.

“We don’t have a pipeline problem. We have an investment problem. If we had everything they had over there — computers, iPads….” Starnes said, pointing in the direction of the freeway.

Three miles away, Palo Alto High School recently unveiled a 23,000-square-foot, two-story Media Arts Center in a grand opening ceremony that featured Arianna Huffington and actor and alum James Franco. The building is the product of a $378 million Strong Schools Bond that Palo Alto voters passed in 2008.

And so what started as the dividing line of Highway 101 became this absurd socioeconomic chasm.

If you visit Gertrude Wilks today, a banner for the non-profit she founded 50 years ago, Mothers for Equal Education, still hangs above her garage door.

A black man is president, but Wilks, who had a hand in making affirmative action happen at Stanford, has buried three of her children. One went to prison at 22, and then emerged at 27, walking with a cane and with glaucoma in his eyes. No lawyer would take his case. One went to Harvard for graduate school, and then died of cancer. Then the third died of cancer too.

Meanwhile, after six decades, Hoover never gave up on his community. His center has been taking in about 150 former prisoners a year. He says counseling them back into the workforce is like his work mentoring teenagers from years ago. Being in prison has taken away their agency. They are told when to eat and when to sleep. They have to re-learn how to make decisions for themselves, how to manage their finances and how to manage their emotions.

He often remembers something Stokely Carmichael told him decades ago:

“If you’re going to do this work, you have to realize that most of the stuff we’re working for is not going to happen in our lifetime…. For someone like me who has been doing this for more than 50 years, it’s frustrating. Sometimes you think, racism is always going to be here. It’s so deeply ingrained in American psyche and culture. I don’t know if we’re going to overcome it. I guess for me — I do whatever I can to build this community. But in the end, most people like myself who have done this work for a long time have ended up helping a lot of individuals — young people — who through our nurturing, through our teaching and mentoring, have learned how to be successful in society. They’ve gone out in society and their lives are pretty good. But you can’t create a large enough number of those people and have them all come back to this community.”

*Historical census data didn’t count the Latino population in 1960. By 1970, 12.1 percent of Santa Clara County’s population were “persons of Spanish origin or descent,” so there was probably some percentage of the population that was Latino at that time.

The featured photo at the top is an aerial of East Palo Alto and the Dumbarton Bridge from Doc Searls.

Thanks to documentarian Michael Levin of Rebooting History, The Spatial History Project at Stanford University, for help with this piece.