Editor’s note: Laurent Gil co-founded Zenedge after witnessing a major DDoS attack where cyber-terrorists took down a colleague’s company network for several days, costing the organization $1.2 million in revenue.

The “Year of the Hack” will probably be one way that 2014 will be remembered. But it actually began in 2013 with a phishing email sent to independent, mid-sized air conditioning vendor Fazio Mechanical.

2014 hacks kicked into high gear with the resignation of the CEO at one of the nation’s largest and most recognizable retailers — Target. It then steadily progressed to see similar attacks on other major retailers like Neiman Marcus and Home Depot, and even financial institutions like Chase and J.P. Morgan. It finally exploded in November with a monstrous cyber assault against a major entertainment brand, Sony, drawing concern by the private-sector and the ire of our own government.

There are clues to how hacks that began in 2013 (some even earlier) continue to reverberate, even as we begin a New Year.

Target’s massive data breach illustrated that no matter how secure the internal cybersecurity of a major organization may seem, malicious attacks can come from anywhere, even from the smallest, most innocent-looking partner.

We all know the stats: The 2013 Target breach cost the company 475 employees at its Minneapolis headquarters (1,175 if you count the 700 unfulfilled positions); $200 million, minus $38 million, of a $90 million insurance policy; 40 million compromised credit and debit accounts and the personal data theft of 70 million consumers. Untold damages to the public trust piled up. The CEO resigned, a CIO was introduced, and more than 140 lawsuits were brought against the company.

For 19 days in 2013, the names, card numbers, expiration dates and security codes of 110 million Target shoppers were flagrantly stolen, and the retailer has worked all year to contain and repair the damage.

Now multiply those damages across a dozen Targets, Home Depots and Sonys. It paints a grim financial picture.

How Do These Hacks Happen?

Let’s start with Target: While protections seemed adequate across Target’s internal systems, the critical failure occurred outside, in the larger network ecosystem, which included a small HVAC contractor. Malware wormed its way into the organization’s POS via an email exchange between the two companies, and the rest is history. After injecting a virus into Target’s payment systems, cyber thieves had full access to consumer payment information, stealing at will and ultimately selling the data to underground markets, where thieves are believed to have recreated credit and debit cards to make fraudulent purchases.

This pattern hasn’t changed. Home Depot and Neiman Marcus suffered similar events, with thieves easily infiltrating one sector of the organization, only to gain access to every digital system. The origin of Sony’s hack is thought to be, surprisingly, the same office breached during its 2011 PlayStation hack – meaning a known hole, albeit a small one, was never secured.

Even scarier is that still today, the majority of large companies neglect to view unlikely access points, like small business units or external vendors, as part of their security ecosystem, leaving unguarded a vast number of digital portholes. Think about it: How many tiny, seemingly inconsequential business units make up S&P 100, or Fortune 1000, company networks, all connected via email or cloud services that don’t use strong encryption or malware technology? And how many mom-and-pop vendors do business within these large networks every day?

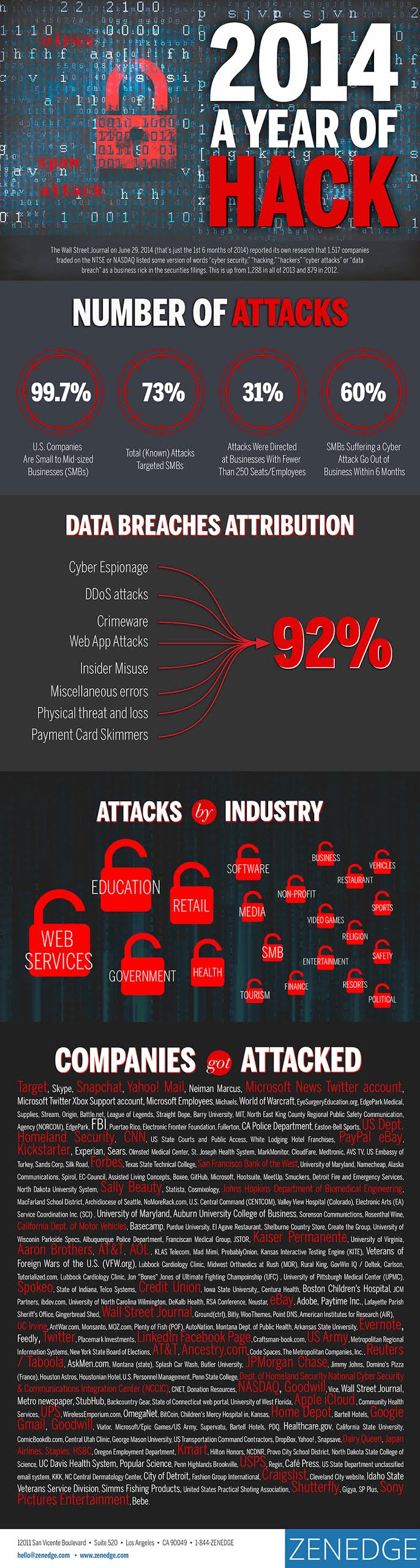

Each major data breach has offered a teachable moment for all businesses, illustrating that it’s no longer enough to erect an impenetrable wall around a single digital infrastructure to ward off threats. Target in 2013 should have sounded a resounding alarm that the target of a hack doesn’t matter: The National Cyber Security Alliance (NCSA) even issued a report shortly after that one-third of all cyber attacks now go after small- to mid-sized businesses.

A mid-2014 study found that targeted attacks against SMBs nearly doubled in 2013 from the year before, and predicted 2014 would hold more of the same. Scarier still, 80 percent of SMBs still have no web security system in place, only 50 percent deploy basic Internet security practices, and 50 percent do not back up their data.

While many implement basic lines of defense, like firewalls, intrusion prevention systems (IPS), gateways or AV software — this is akin to thinking an umbrella will shield you from a missile launch.

Of course there are challenges to plugging all of the holes across a business ecosystem’s network: Corporate infrastructures, culture and even varying degrees of IT understanding can hinder standardizing security platforms and protocols – both vertically and horizontally across the commerce chain.

And then there’s the biggest hurdle: cost. What is universally agreed upon is that good defense is time-consuming and expensive, although it might look like a bargain when we hear stats like this: The U.S. House Small Business Subcommittee on Health and Technology shows roughly 60 percent of small businesses hit by cybercriminals shutter with six months of an attack. Sony’s underinvestment in security may cost in excess of $100 million, and subject the firm to years of lawsuits from past and current employees over stolen private data. Target will see more than 140 lawsuits head to court in 2015.

The fact remains that hackers are constantly testing for weaknesses and holes, and those holes are often in small units that appear organizationally insignificant, until their connection to the larger network is exploited. As we’ve witnessed all through 2014, once the door of a neglected SMB partner or via a semi-protected internal department is pushed open, it is quite easy to gain broad-network access to the larger organization.

A Shared Responsibility

To combat such massive, organization-wide breaches, security is increasingly looked at by corporate boards and enterprise IT departments as a shared, contractual responsibility between large business, smaller business units, and even the external vendor network. It works something like this:

Enterprises are essentially taking a page from the history books and designing security systems reminiscent of medieval fortresses. Imagine a defensive wall around the village that surrounds a castle — with hackers confronted first with fortified external systems, and therefore unable to penetrate even that 10-employee vendor to gain back-door entry into their larger target.

What is created is a system of autonomous and independent, yet interconnected, defensive barriers around individual business units (like subsidiaries, sub-firms, branches, divisions and departments) that make it necessary for thieves to scale multiple walls. Even if one wall is compromised they are confronted with another, and another, and another wall.

And while security protocols are managed and “owned” independently, they are also continuously updated and monitored in real time by a centralized system. The idea is that if each unit is autonomously fortified, yet housed within a common administrative “dome,” the likelihood of a one-and-done, organization-wide breach is dramatically reduced.

This approach is being applied internally across organizations, but it may be a while before all small business units and external vendors are also looped into these systems. Ultimately, with external and internal systems acting as autonomous security perimeters, headquarters will be able to monitor each as a standalone system – and someday even coordinate joint dynamic, real-time security protocols across the larger network when thieves start testing for weaknesses.

By building and extending these syndicates of unique-but-cooperative security systems outward, firms will present a more united front against cyber thieves and make attacks the scale of Target’s and Sony’s substantially less likely.

Target started us down this path to the “Year of the Hack,” and still remains a painful reminder of what happens when a network fails to fortify every access point. Its breach illustrates the damage the tiniest fissure can cause, and a lesson that cybersecurity is not a solitary endeavor. Face it, when a hacker sees an opportunity, he or she doesn’t care if the unguarded door has left open by an office of 100,000 or 10. All they see is a Target.