Say the words “California and economy” and most people today think of Silicon Valley with its multi-billion dollar valuations and manic focus on what’s going to be the next Square or SnapChat.

But drive inland from the Pacific Coast and other valleys open up. Valleys steeped in history like the Salinas, the San Joaquin and Sacramento. Stretching literally as far as the eye can see are fields upon fields of lettuce, tomatoes, almonds, rice, grapes, wheat and artichokes. In fact, many foods humans can grow to eat will take root and flourish in the state’s fertile valleys. California literally feeds the rest of America.

But it doesn’t always do it easily — as recent droughts have proven. And often, the state’s farmers achieve harvests with massive amounts of technology tucked behind picturesque orchards and perfectly organized fields.

That’s intensely true at California Olive Ranch, an upstart in the global olive oil industry. The company has had to use technology—from moisture sensors in the fields to clean rooms that keep the oil at a constant 72 degrees and tucked away from light and air—to make an olive oil that will compete with the best in the world. The end result is not only a high quality product, but also one inexpensive enough for a majority of American consumers to buy.

Tradition

Olive trees are one of the oldest fruit trees in the world. (Yes, olives are a fruit). Scientists have traced the DNA of olives back 6,000 years or more and archeologists have found olive pits in ancient sites throughout the Mediterranean, which is still where most olives grow today.

In fact, one of the key varieties that California Olive Ranch grows is Koroneiki, an olive that is piquant and spicy, and has been growing in Greece for 3,000 years.

For much of their long history, olives have been harvested and milled using traditional methods that date back thousands of years. Olive plants mature into trees over several years and are harvested primarily by hand with people using rakes to pull the fruit off the trees. It’s labor intensive and time-consuming. To make olive oil that was good and reasonably priced,

California Olive Ranch would have to adapt olive production to a very different method of growing and harvesting, says Gregg Kelley, the company’s CEO.

“It’s what we call ‘super high density’. The first acreage was planted outside of Barcelona in 1996,” he says standing in one of the company’s fields about 40 miles west of Chico, Calif. “This type of orchard has only been around 18 years anywhere in the world.”

Look out across the orchard and you may be able to tell what’s growing there. It certainly doesn’t look like trees, let alone olive trees, which look much like any other orchard crop with big trunks and boughs. Growing the “super high density” way means planting olives as hedges that are trained through pruning to grow up a dozen or so feet high instead of branching out.

By growing olives in rows, like wine grapes, California Olive Ranch has taken most of the human labor out of the harvest. Instead of an army of people using rakes, enormous mechanical harvesters shaped like a very tall upside-down “U” move through the fields at about a mile an hour. They ride over the top of the hedges and shake the olive trees, dramatically forcing the fruit off the plant. The olives drop down into a cache and then move up what might be called “olive escalators” that dump the fruit into giant gondola-like trucks that capture tons of olives every few hours.

“We looked at a lot of traditional hand-harvested crops and thought about how to take it to the next level, how to mechanize it. It mimics the hand-raking process,” says Brian Mori, a grower/field representative who was on the team that helped take what had been wine-grape harvesters and made them work for olives. In the end, he says, “we had to build a tree to meet the needs of the harvester.”

While the trees look substantially different from traditional olive trees, they are still what head miller Bob Singletary calls “an incredible piece of work.”

“These trees are self-pollinating, they grow a specific olive and there’s no cross-pollination. We have this unbelievable tree producing fruit for us,” he says in a tone that doesn’t border on reverence—it is reverent. “We have to take care of it.”

Technology

While technology might get a bad rap in agriculture sometimes, at California Olive Ranch it’s designed in great part to do just what Singletary says they must: take care of the trees.

For the first eight years of operation, California Olive Ranch was run “almost as an experiment,” Kelley says. But when he was hired he brought the belief that technology, used well, could change how olive oil was produced in a place where labor is expensive and the arid, harsh environment can be unforgiving.

“I can’t escape the technology, maybe it’s a character flaw,” Kelley says of himself, since his first career was working in Silicon Valley during the first Internet bubble in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He was the typical start-up entrepreneur living a fast-paced life.

“I had accomplished everything I wanted to accomplish professionally,” he remembers. But driving home one day he caught sight of himself in the windows of a building on Van Ness Street. “I had all the fancy stuff you’d want to have as a 20-something, fancy car, fancy clothes, eat in fancy restaurants, but I was miserable.”

He wasn’t happy with the way business worked—and still does—in much of the startup world.

“I had all the fancy stuff you’d want to have as a 20-something, fancy car, fancy clothes, eat in fancy restaurants, but I was miserable.” Gregg Kelley

“It was built around the perception of value, selling that perception of value and making money off that perception,” he says. “I remember to this day seeing my reflection and thinking, ‘You look like an absolute idiot.’”

The next day, Kelley bought a Jeep Wrangler and started wearing jeans to work. He jokes that he was going through a midlife crisis at the age of 29. He ended up helping to sell off the company where he was working and merging it with another company. Then he bought a one-way ticket to Heathrow Airport and traveled for two years.

When he returned, he ended up in Chico, where his brother was living. “I had no idea what I would do,” he says, but he loved that people said hello to him on the streets of the small town surrounded by farmland.

He came across California Olive Ranch on a farm visit. At the time, it was a single ranch with a single mill. But his interest was piqued by the way the company wanted to grow olives. “It helped make the connection between my former life in technology and that grounded life I was looking for,” he says.

He brought that business acumen to California Olive Ranch, traveling to places where they have been growing olives for millennia, like the Italian city of Puglia and Andalusia in Spain, to do research and learn the business.

He and his team would ask, “Why do you prune this way, why do you blend that way? And all too often the answer was ‘it’s just the way we do it,’” he says. “But we needed the answer. So we took the path of collecting information on everything we do.”

The company knows every root and nursery stock that is planted in its fields, as well as the fields of farmers who supply to California Olive Ranch. There are weather stations in every single orchard. There are moisture probes in every field so they know exactly how much moisture is taken up through the roots. They track every load from every field to the mill and then the oil is tracked into the bottle.

That obsession with data has led to big changes in the way the company treats its trees and the land they grow on. This is big data, used wisely, that can help change the phrase “it’s always what we’ve done” to “the data tells me to do this.”

For instance, California Olive Ranch used to irrigate its fields with 2.5 feet of water per acre but realized through data that it was watering too much. Now growers irrigate at 15 inches per acre.

“We also realized we were giving too much fertilizer to the trees. We used to put too much nitrogen on them, treating them like an almond or walnut tree. We’ve reduced that to almost nothing and last year we didn’t use fertilizer,” Kelley says.

In the end what’s most important is what happens in the 40 to 45 days of harvest that runs through much of September and October. Then it’s up to the humans, the millers and quality control scientists, who will taste almost every oil milled out of the hundreds of truckloads that go from field to mill during harvest.

“We have 60 truckloads with 60,000 pounds of fruit a piece coming in every 24 hours,” says Singletary, who estimates he consumes about a quart a day during the harvest. “I taste the oil twelve to sixteen hours a day.”

Taste

Very few human hands actually touch the fruit from the time it starts to ripen from bright green buds through to a deep dusky plum-colored fruit.

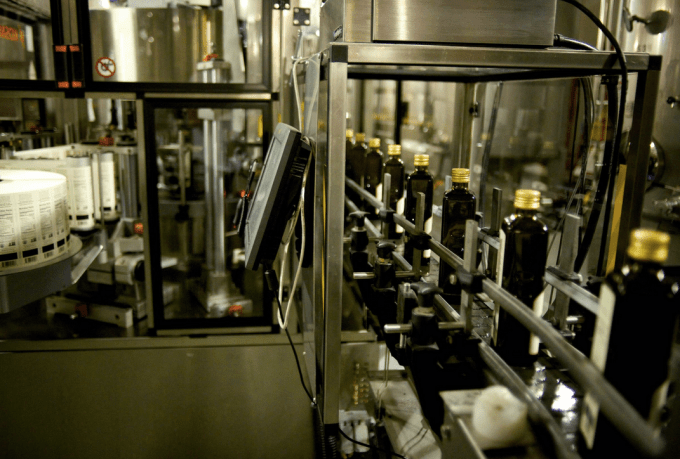

And no hands will touch the olives once they go into the mill. There, quality control with its clean rooms and stainless steel tanks take over to protect the oil.

But as Singletary says, it will be tasted throughout the process. While technology and data can get the fruit to the mill and into the bottle with a lot less fuss and cost, nothing takes the place of human noses and taste buds to detect the differences in flavor profiles.

“My favorite part of the job is walking down the mill, tasting the different flavors, line to line,” says Jim Lipman, vice president of operations. “The oils we tasted today were very grassy. I had oils last week that tasted like bananas. From the trees to the olives, it’s a new discovery every year.”

It may seem crazy or just plain gross, as technical services manager Mary Bolton thought when she first tasted olive oil. “Probably the first time I drank oil, it was the most disgusting thing I’ve done. Now it’s like eating cookies.”

Tasting is the only way to know if the oil is still retaining its piquancy or if it is starting to mellow. Mixing different varietals—adding the sharp Koroneiki to the more floral Arbosana or grassy Arbequina—will create the specific taste Bolton and Singletary want.

“We have 18 different oils with different intensities. When you finally hit the blend that is really a wow factor,” Singletary says. “Our miller’s blend takes all three varietals. You taste the freshness of Arbequina, the floral of the Arbosana, the Koroneiki for the kick.”

“What’s most appealing in contrast to my other life where everything was so fast, temporary and really aggressive is that the cycles within agriculture are much longer term. Things happen over five-year cycles, not five months.” Gregg Kelley

But if you think tasting oil is simple, consider that there are specific tulip-shaped, blue-colored glasses for tastings. There’s a ritual of warming the covered glass with your hands to bring the oil up to about 80 degrees. Then you bring the glass to your nose, uncover it and breathe in the scent. Tip it to your lips and let the oil coat your mouth. Now comes the strange part. Press your tongue to the top of your mouth and suck in air. You’ll make a husky “hee-hee” sound. The air flowing across the oil drives the taste and scent through your mouth and into the back of your throat.

If it’s great olive oil, it absolutely won’t taste mellow or buttery. And it certainly doesn’t taste like table olives.

“Your throat catches on fire a little bit, you might even start coughing. That’s what great olive oil is supposed to taste like,” Kelley says. “That’s the healthy part of olive oil, it’s the bitterness and pungency, the fruitiness, like freshly squeezed orange juice. This is freshly squeezed olive juice.”

The tasting for Kelley also is about watching the cycle of farming come full circle from planting a tree to tasting its fruit. “What’s most appealing in contrast to my other life where everything was so fast, temporary and really aggressive is that the cycles within agriculture are much longer term. Things happen over five-year cycles, not five months.”

That’s the romance of agriculture, Kelley says. “Here you build from the ground up. You take your time and do it right the first time because the actions you take today will have an impact two, five, 10 years from now.”