Anonymous messaging app Whisper has suspended its editor-in-chief Neetzan Zimmerman and other staff members after Senate Commerce Committee Chairman Jay Rockefeller wrote a letter summoning Whisper execs to an in-person meeting to discuss the app’s privacy practices.

“While Whisper provides users a unique social experience, the allegations in recent media accounts are serious and users are entitled to privacy policies that are transparent, disclosed, and followed by the company,” writes Rockefeller.

The Guardian has written several articles accusing the app of breaching user privacy and reporting that members of Whisper’s staff showed the Guardian how its database could locate users within 500 meters (a little less than a standard city block in distance) of their location, including those who had asked not to be tracked. Zimmerman shot back on Twitter that the accusations were “vicious lies.” He then continued on a 20 post tweetstorm in an attempt to clear up what he said was misinformation surrounding the data that Whisper gathers.

Senator Rockefeller sent a letter to Whisper CEO Michael Heyward late Wednesday asking for a meeting with him and his staff so that Heyward could explain how the app tracks users. Neetzan’s Twitter account has been silent since Wednesday, following several rants about what had been happening.

Heyward said he will continue to discuss the inner workings of Whisper with the public and released a point-by-point letter Friday, addressing the latest Guardian article about Whisper being summoned to Capitol Hill. In it, Heyward suggests that the Guardian has gathered incorrect information from non-technical people, including editorial staff at Whisper.

Whisper accused the Guardian of quoting staff who were not aware they were on the record, including one such conversation in which editorial staff showed two Guardian reporters how they would be tracking an apparently sex-obsessed D.C. lobbyist “for the rest of his life.”

The back-and-forth argument on tracking gets a bit nuanced here. The Guardian had reported that Whisper tracked location in two ways, one being GPS location and another by use of IP addresses for those who have not opted into location tracking on the app. “For example, if a user is soliciting minors, we will share the limited information we have with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children,” wrote Heyward.

The Guardian claims Whisper rewrote its Terms of Service and added a new section about privacy just four days after learning of the Guardian’s plans to publish its expose. Whisper includes concerns about suicide in its new privacy policy section:

Whisper is meant to be a safe place. There may be situations where we may need to disclose the information we may have about you for the greater good, such as if we see suicidal statements or statements that involve the intent to harm oneself or others, or learn information about missing children, or threats to the community.

Suicide has been a popular topic on the app, particularly among military personnel.

It seems that Whisper is readily admitting how it tracks user info but the Guardian is inferring this is a common practice outside of Whisper’s claims to only use this info in “extreme law enforcement cases.”

Whisper had admitted earlier that it hands certain information over to the Department of Defense and other government organizations. However Zimmerman downplayed what that information was, tweeting that Whisper only collects data on the number of times suicide was mentioned, not actual location information.

Whisper’s senior vice president, Eric Yellin, wrote in an email exchange with the Guardian prior to the first article being published that Whisper used IP addresses, “to determine very approximate locations.” The Guardian claimed this put Zimmerman and Yellin at odds in respect to how Whisper operates. Heyward claims Yellin meant this for cases of safety, not as a practice used on the general Whisper community.

Whisper had said earlier that it does not track users “passively or actively.” That’s a bit of a head scratcher, though. While Whisper may not be able to track the exact address of a user, it would seem having the ability to track a user’s location within 500 meters and also tracking IP addresses of users who have opted out of GPS tracking for the express purpose of handing that over to the government would be considered both passive and active tracking. As Heyward writes in the letter:

“Previous locations of posted Whispers may be taken into consideration when evaluating the veracity of a user’s claims for editorial purposes. For example, if a user claimed to be a doctor treating an Ebola patient in West Africa, and never in fact had any Whispers posted in West Africa, our editorial team would not feature the post.”

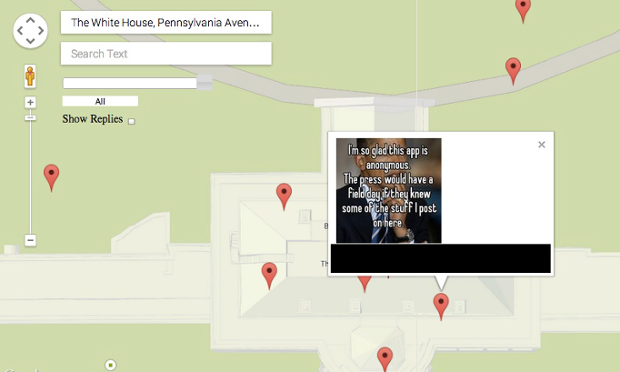

Heyward asserts in the letter that Whisper drops IP address info after seven days. However, this seems counter to a later paragraph in which he addresses the Guardian’s concerns over storing user data “indefinitely.” The Guardian reported that info was readily available at any time using an in-house mapping tool that allowed editorial staff to search posts and verify their authenticity in order to feature them on the site.

Photo credit: The Guardian.

Heyward defends this practice, explaining that it’s a feature that allows users to search for old posts, not something that can identify individuals or their location. This one also ends up being a tricky argument. The Guardian claims Whisper staff can search and identify people, using their post info. Heyward says it’s just the post, not the individual info that is associated with the post that gets stored sine die.

Is this just semantics over what constitutes passive and active storing of information or a nuanced misunderstanding of how the privacy sausage is made? Is Whisper hiding something, as the Guardian claims? Is the Guardian a bunch of “alarmists,” just “outright lying and totally wrong,” as Whisper claims? No date, to our knowledge, has been set yet for Whisper execs to meet with Rockefeller and sort this out. But what is clear is that if you are thinking of committing an illegal act, you should definitely not post that on Whisper. That is, unless you’d like the government to go knocking on all your neighbors’ doors about it.

Note: We’ve reached out to the Guardian to find out if the above map is an illustration of the in-house mapping tool or an actual example provided to the reporters. We have not heard back yet, but will update this post as more information becomes available.