Editor’s note: Tadhg Kelly is a games industry consultant, freelance designer and the creator of leading design blog What Games Are. You can follow him on Twitter here.

Across 2013 and into 2014 the stories around games went in many directions, to Steam and Steam Machines, to consoles, to VR and microconsoles. It could be said that a considerable degree of the anima behind those stories was driven by hunts for the next big break in video game platforms. Where, people asked, would another Facebook or iPhone style explosion come from? Where would lean product and plentiful players be found anew?

Steam got full quickly, microconsoles struggled to find an audience and console feels like a repeat performance of its previous generations to the same crowd as always. My posited ultra-handheld device category is still in the mysterious future and tablet sales have slowed. There are certainly interesting developments – smart watches, virtual and augmented realities and whatnot – but none seems to have the scope to really hit like mobile did. We may be seeing the audience just settling in with what they have.

Familiar Shapes

In 2014, despite everything else, it’s still all about the smartphone. PC sales may be up and Sony may have sold a fair few PlayStation 4s, but Apple sold 10m iPhone 6’s in a weekend. And when you think about it that makes a lot of sense. Potential platforms are more specialist than the smartphone. You’ll use VR in certain circumstances and your tablet in others, but you’ll likely have your phone with through all of those situations. Phones handle all of your quick computing, your easy access apps and a variety of other media functions too (photos, music, etc). Of course phones would remain the core around which everything else you do would work.

Those of us in tech and games are conditioned to expect total revision every two or three years now, almost to expect it. But it’s not really happening. Though they may have bigger and smaller sizes and new features, the smartphone looks to be as durable a paradigm as the PC has been. 20 years from now we’ll largely still use them in much the same way as we do today. They’re not going anywhere. There will be an iPhone 7, 8, 9, 29, and 209. Well maybe not that last one, but still. Perhaps it’s okay to assume that we’re moving into a phase of relative platform stability.

So what does that mean for games? Sometimes the games industry settles into a routine, a way of being where recent innovations are absorbed and exploited. At those times it’s less about what’s new and exciting in technology or business and more about simply putting what’s out there to good use. A key canary in this particular coal mine is the way that developers drift back to looking for publishing money. Another is the way that brands start to reassert themselves, and how licensed content starts to seem like an attractive business model. A third is how games stop hitting the headlines outside the usual channels.

Primarily though it’s watching how, with the old order having been previously unseated, new orders start to morph into next year’s old orders. In mobile gaming this started to happen about 18-24 months ago. As the iPhone got all full up things like the cost of user acquisition started to rise and the prevalence of incumbent games sitting at tops of charts became all too apparent. We slowly started to see the tail off of breakout games (with Flappy Bird acting as the great exception) and an increase in talk of bigger budgets, more competition on visuals, a need for game companies to get good at PR, speculation over the power of YouTubers to overcome discovery woes and subsequent speculation about the ethics of sponsored coverage in that medium.

All of this is essentially the move toward stability.

Two Roads

When platform are in their unstable phase, nobody knows anything the rules for success are anarchic. Games that “should” succeed totally fail whereas games that shouldn’t ride the waves to monstrous success. However when stability does begin to emerge it tends to mean that two avenues for success form, and the degree to which they are success depends on the particular platform.

The first road is to sell games based on distribution-led strategies. Thats’ where all that talk of user acquisition, retention, advertising, paying for clicks and views and plays and installs and so on comes in. That sort of thinking usually surfaces early and settles on a variety of tactics for success, and it usually drives some notables in the space. The sense of conventional wisdom moves quickly but adopts relatively comfortable shapes, and both startups and investors buy into that wisdom (regardless of how true it is: a good example is that gaming startups and investors often still believe that mobile game companies should strive for a catalog of releases – even though all the data says otherwise). For those that get in on the ground early this is the time when you see big exits from companies that only formed 3/4 previously.

However this approach tends to tap out. While the process-oriented side of the business tends to figure out the early shape of what works in any platform it also tends to red-ocean itself into stasis pretty quickly. Companies that operate that way never really know how to value creativity and their culture eventually winks it out, leaving nothing but stat-head thinkers who get trapped in you-can-only-improve-what-you-can-measure thinking. Ultimately they stall, sometimes even falling back just as quickly as they first arose. It turns out that for all their structure and process the product that they’ve built engenders little true loyalty. It’s just a game, same as any other.

This is where the second road starts to matter. it’s the game developer who treats their game as a piece of media, of art. They focus on selling the vision of the game, of building a pre-selected audience and a marketing story. Rather than make the conversation all about business, they make it about the journey, about the magic of the game, the thauma, the fiction and the promise of what it will be. This path is as completely different from the business-led path as HBO and other cable television channels are to regularly broadcast TV. Broadcast is a world of low-rent product that sells based on reach. HBO is a world of selling on quality, on vision and voice. And usually it comes after the business wave, after the first roaders have done their thing.

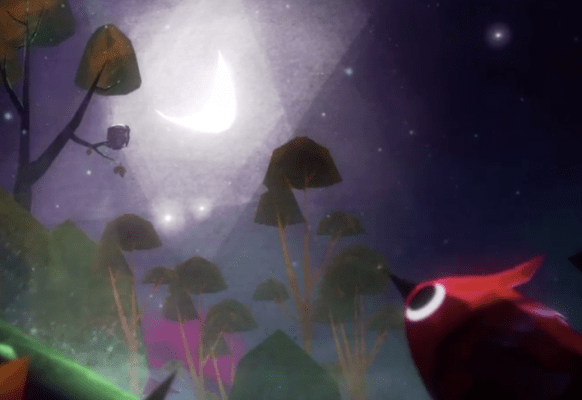

Is that happening in mobile? I really hope so. One encouraging example of this is Robin Hunicke’s studio Funomena, working on a new game Luna (pictured above). At the Mobile Games Forum in Seattle this week, she stood up on stage and talked about its artistic influences, the kind of experience she was trying to create and the importance of games-as-art and finding not just customer but a fan, of building a relationship. Another is the wonderful adventure that is Monument Valley. Speaking about what it’s like to develop that kind of game, lead designer Ken Wong is keen to stress how the studio maintained an entirely quality-first approach. A third is Camouflaj’s episodic game Republique, which continues to try to make storytelling/adventure work in this new space.

Beyond a certain point every platform needs its artists to keep it growing. It takes orthogonal thinking by people who aren’t businesslike to engender a wider and more lasting conversation, to find the new genres, new ideas of what might work and so on. The reason I say “I hope so” that these kinds of games are happening in mobile is bigger than simply saying I like cool games though. I do, but I also mean “It’s not certain”.

But Where’s Our HBO Equivalent?

Artists need organizations structured to support their efforts. They need patrons. In console gaming that patronage layer exists with some publishers and platform holders like Sony, people who can offer an umbrella in which quirk can be allowed to manifest and sometimes come good. On PC Steam sort-of offered an environment that permitted that to happen, although Valve didn’t actively fund many of the games on there.

In mobile, however, patrons are lacking. There are publishers, some of them ambitious, some of whom talk in terms of helping developers and giving them fair deals, but none of them really constitute patrons yet. They’re too meat-and-potatoes still, usually operating with limited remits and asking for big business cases to be proven around potential games before they’ll invest. And so it’s left to individual developers to secure financing in an uncertain landscape. That kind of effort is rarely scalable.

HBO style TV needed HBO to make it happen. Without that organization TV would have stayed in the hands of process thinkers and never gone much beyond game shows and soaps. Gaming is much the same. Mobile games could do with a more ambitious kind of publisher, but we’re not really seeing that yet. Aside from hearing Robin Hunicke, the vast majority of the day’s conversation at MGF was still very meat-and-potatoes. It was talks about the psychology of winning and monetization techniques, app discovery strategies and what packages to include in your game to improve performance. Still very first-road in other words, still just about process. And it’s been like that for a while, essentially just repeating and repeating.

Will anyone step up and rethink mobile publishing and bring forth the next wave of mobile games? That is the question.