Three years ago, a few months after the Arab Spring demonstrations forced a collapse in the Egyptian government, twenty-year-old Marwan Roushdy spontaneously entered a Startup Weekend competition in Cairo and won.

It was a mobile app that connected users to emergency hospitals in the immediate area, and it was called Inkezny, the phrase for “rescue me” in Arabic.

The win turned Roushdy, then a construction management major, into a bit of a tech celebrity in Egypt. He ended up being quoted widely on CNN and The New York Times about the promise of entrepreneurship in transforming and revitalizing Egypt’s economy. The Arabic-speaking world is an enormous opportunity; with close to 300 million speakers globally, there are nearly as many Arabic speakers as they are English-speaking ones. At the same time, many online business models taken for granted in the West have yet to be localized for Arab markets.

Three years later, everything is different (or not). The Arab Spring ended up petering out, with Egypt electing another military strongman in Abdel Fattah el-Sisi this year.

And Roushdy has moved to Silicon Valley, where he’s launching a company called Complex Polygon with $1.7 million in funding from some of the Valley’s best-known investors, including Greylock Partners, SV Angel, Chris Sacca’s Lowercase Capital, CrunchFund (which is owned by TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington) and Khosla Ventures. His co-founder is Addison Hardy, who has worked with startups like Everest and Connect.

Their first high-profile product is a photo-sharing app called Swipe. (Yes, a photo-sharing app.)

The app is a mash-up of several different trends right now.

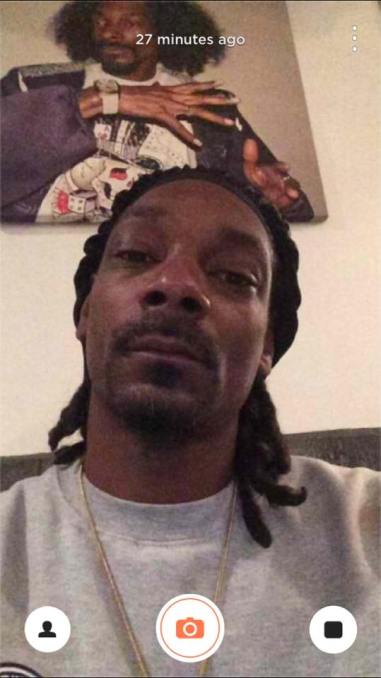

It’s “anonymish.” Your friends share different photos but you won’t know exactly who took them, even if you have a pretty good idea (like Snoop Lion, pictured above).

It’s got a Tinder mechanic where you swipe left or right to like things. Or up if you want to comment on something.

It’s ephemeral. You only get to see photos once.

How did Roushdy and Hardy end up here?

They wanted to build something fun that would be universally recognized; they structured Complex Polygon as a startup where they could spin out idea after idea to see which one stuck. Swipe is their second one, and it had enough promising engagement metrics that they decided to do a bigger launch.

“There is something incredible about creating a brand that everyone recognizes: Facebook, Snapchat and Instagram are probably more recognized than the most popular movie or song out there,” Roushdy says.

And then there’s this very stark reality about building consumer Internet and mobile products — people have to use your product every day, in order for it to grow.

So that cancels out a lot of really good, worthwhile ideas that might attract only infrequent, if important, use. If people only need to use Inkezny a couple times in their entire lifetime, how will it spread from user to user?

In another example, I met a startup a month or so ago at San Francisco’s City Hall that was working with seismologists to provide earthquake warnings that give people up to two minutes of advance notice ahead of quakes via text message. It’s a product that is sorely and clearly needed in the earthquake-prone state of California, and it could actually save lives. But realistically, the only way a product like that would get distributed is probably through state law or a federal system like the AMBER Alert, because it would be too hard to get 38 million Californians to collectively download one app that provides no immediate entertainment or benefit. Such is human nature.

Y Combinator partner Garry Tan recently wrote a blog post about how this problem affects startups in the travel-planning space. He said travel-planning software is one of the most common bad startup ideas he gets pitched:

This points to the deeper problem that underlies every product or service: obscurity. I only have a finite number of slots in my brain. If I don’t remember it, I won’t use it. And I only remember things that I use often. Just like I order Coca Cola whenever I get a cheeseburger… the consumer web/mobile services I use need to be things I use all the time.

Which leads us back to trip planning. How often do people really plan trips? For the typical working adult, probably once or twice a year if you’re lucky. In fact, Americans are notorious for shirking vacation, clocking the lowest rates of vacation on the planet. Twice a year just doesn’t cut it.

This constraint is why so many founders seem to end up working on totally silly, seemingly trivial things in the consumer space. Once every several years, one of those trivial ideas happens to turn into something like Twitter, which transforms the way in which society consumes news and spreads information. That so many small teams of founders seem to be working on photo- or video apps is just evidence of how insanely high the failure rate can be. Everyone is looking for that small, simple fun mechanic that can just explode unexpectedly. It’s a totally different set of constraints than in the enterprise space, where startups tend to generate revenue sooner in their lifecycle and grow more gradually. Or in bioinformatics or energy startups, where there are high upfront capital costs.

Even so, Roushdy was a bit sensitive about Swipe being a photo app.

“I don’t think anybody should be hated for working on something they like,” he said.

Well, no, I don’t disagree with that. Swipe is a simply, easy-to-learn app that all the right investors seem to be using. Hell, even Snoop Lion is using it. Several designers praised the invite system, which has you swipe left or right to add new people to network. It’s a pretty smart viral growth mechanic. And while Roushdy didn’t want to publicize growth numbers, they’re promising.

That said, it can be frustrating at times to see so many talented people focusing on mobile-social apps. However, I’m probably more disappointed in founders who have already made it professionally or financially working in this area, as opposed to newcomers like Roushdy, who are coming from countries like Egypt to try their hand at the game.

“When I was growing up both Addison and I really wanted to build games,” Roushdy said. “That’s how we both started programming. We realized that games waste people’s time, but something like this is both entertaining and helps people stay connected. We were both also very interested in design and psychology and creating brands that iterate really fast.”