Editor’s note: Cyril Ebersweiler is the founder and Benjamin Joffe is general partner of the hardware startup accelerator HAXLR8R (“HAX”). Both have been living in China and Asia for over a decade. This is the fifth part of their series on “Lean Hardware.”

So far HAX startups have run 20 successful campaigns, making us the most prolific investor in crowdfunded hardware projects. As active participants and keen observers, we identified a few ideas that could help creators, backers, media and investors.

The Better Mousetrap Myth

Will the world beat a path to your door with a new smartwatch, 3D printer or drone? Unless you have something much better or very different, it will likely be at the cost of your margins.

Out of the 47 3D printers that raised over $100,000, the jury is still out there for how many will ship, how many will turn a profit and how many will become full-fledged small or large companies.

Some products like “slim wallets” can be successful servicing a small customer segment but are hardly startup material.

Campaigns Are Not Created Equal

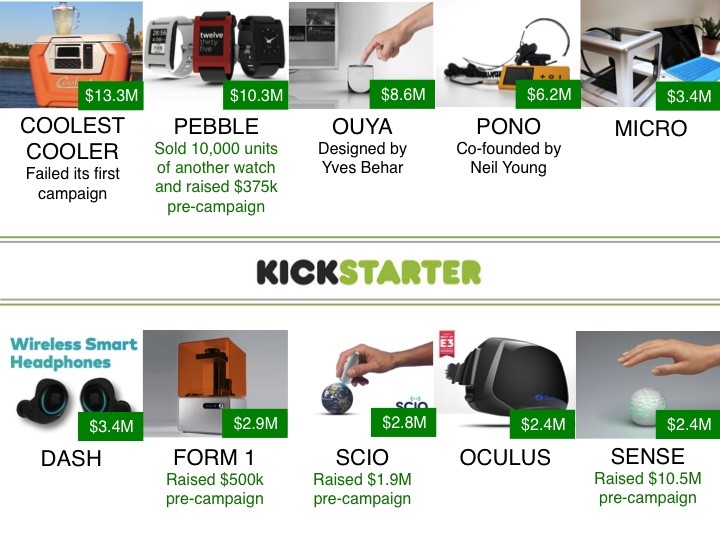

Bad planning leads to bad surprises. Among the most successful projects, a good number raised venture capital prior to crowdfunding, often thanks to high-profile founders or strong technology. While it helps polish a campaign, this is no guarantee products will ship on time or at all. Creators experienced with manufacturing, or finding qualified support are essential to avoid shipping date slips.

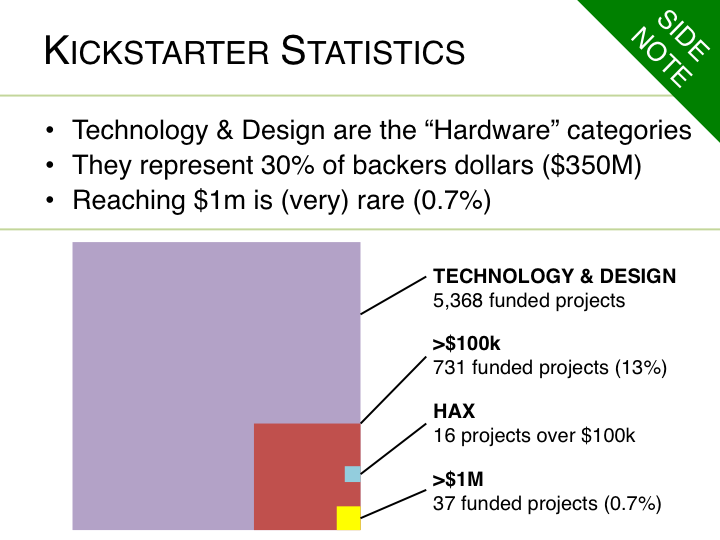

As of September 2014, only 37 projects worldwide in the Technology and Design categories have reached the elusive $1 million mark on Kickstarter (less than 1 percent). Even $100k is not a walk in the park with a mere 13 percent.

Campaigns Don’t Run Themselves

Everyone should know by now, but it seems many still don’t realize that media and backers rarely stumble on your project the day you click “publish.” For many successful projects, the campaign started weeks before launch.

Once the campaign is live, there is much work to do to gather more backers. Quality updates can lead them to increase their pledges and attract more backers.

Bunnie Huang (@bunniestudios), an MIT PhD and “lifestyle hacker” who crowdfunded two projects worth hundreds of thousands of dollars (Circuit Stickers and Novena, an open source laptop) warns us:

“Stretch goals are important but pitch a complete product. Core features in stretch goals might turn off backers. Plan your pledges and find the right service providers to avoid spending time on interactions for small pledges. I had “Buy me a Beer” for $5.”

It Might Not Ship

Only if creators figure out manufacturing! Many have zero experience. Spending just a few days in China for “parachute manufacturing” often fails. Yet, China is the Silicon Valley for Hardware and there is effectively a “cost of not being in China”: better plan for scale than shift plans later on. Shenzhen is also a great base for fast iterative prototyping.

Beyond manufacturing, some projects might simply be unrealistic, ship products that are late or compromised, or be downright scams. We call those NAIVEware, LATEware, LAMEware, SCAMware.

Yes, even smartwatches as explained by the founder of KREYOS who lost the $1.5 million it raised on Indiegogo to a shady OEM partner and shipped, late, sub-standard products. A rare case combining NAIVEware, LATEware and LAMEware.

Evgeny Lazarenko, doctor of engineering and hardware startup guy, warns us:

“Backers should research the backgrounds of creators and their teams. Do creators fully comprehend what they signed up for? There’s a stark difference between industry veterans and fresh grads, the latter being almost genetically incapable of due diligence.”

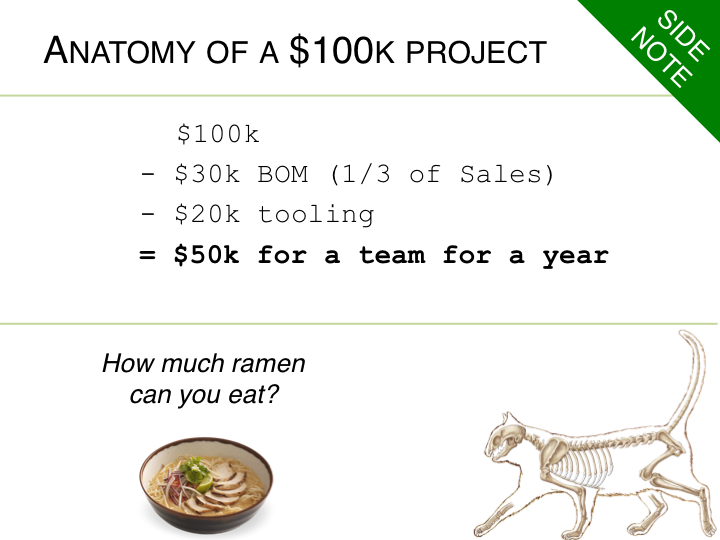

Creators Make Money

While the economics of wallets probably work out, it stays questionable for more complex products such as 3D printers.

Projects Are Not All Original

The intention of crowdfunding platforms is to bring ideas to life, but some “creators” found that doing just the marketing on a product already developed by a third party could work too, such as those bamboo watches.

When taking a walk in trade shows in China, we often either recognize products, or end up thinking “this could totally be crowdfunded.” Will you recognize this one from the former-crowdfunding-turned-pre-order Chinese site Demohour? We bought it for $15 in Shenzhen a month ago.

Funded Does Not Mean Startup

Backers are mostly “Innovators” and “early adopters” (some have misplaced expectations since Kickstarter is not a Store and the recently revised Terms of Use make it clear). Can your product cross the chasm and achieve mass-market appeal? Do you have bigger plans? Are there barriers of entry? Otherwise success can mean being copied faster than you can spell “EASYware.”

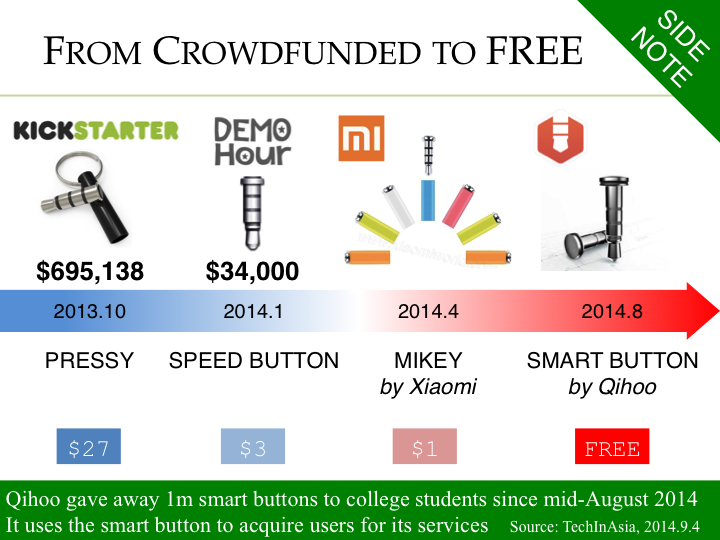

The smartphone button Pressy, which raised close to $700k on Kickstarter, is now a famous case – the latest development is the Chinese company Qihoo giving away similar smart buttons for free to drive people to its mobile services. This is effectively a new business model on top of a copycat product.

Pure hardware is hard to protect: take it apart and it can often be reverse-engineered. These days, beyond designs and patents there is “defensible IP” in software, algorithms, or a community that a crowdfunding campaign can help you build!

Matthew Witheiler, general partner at FlyBridge Capital who wrote great pieces of analysis on crowdfunding data, says:

“Backers are buying a product. Investors are buying a vision. Some products may generate tons of demand (like the Coolest Cooler) but may not be great venture investments.”

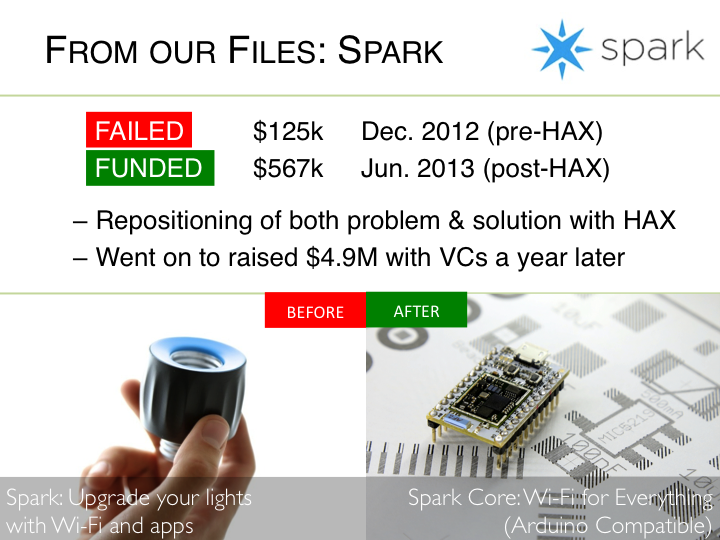

Zach Supalla, founder of the IoT “Wi-Fi for everything” company Spark, which raised over $500k on Kickstarter in June 2013 and $4.9 million VC funding a year later, adds:

“Most companies that launch a crowdfunding campaign don’t have a plan to go from a single product to a huge empire, and that keeps them from being VC investable startups.”

A Failed Funding Is Not the End

Just like a successful campaign can be a “false positive” for startup potential, failing a campaign can be a “false negative” and does not mean there is no hope there. Some companies rise again in spectacular “Phoenix Campaigns”.

The Coolest Cooler failed its first campaign in December 2013. It became the largest project on Kickstarter in August 2014 by raising $13.3 million with an almost identical product. According to its creator, its successful rebound might come from an improved product, support from the first campaign backer, better timing (summer is better than winter for coolers) and overall better preparation.

Spark, mentioned above, repositioned both the problem it was working on and the solution: after joining HAX it went from “Wi-Fi connected lights” to “Wi-Fi for everything” and raised over $500k on Kickstarter.

Failing a first campaign has some advantages as it builds a list of backers and media you can reactivate for your second attempt. Yet, there are often multiple reasons why a campaign fails and figuring those out can be difficult.

In Conclusion

As it evolves, much is yet to be discovered about crowdfunding. Setting the right expectations and anticipating common problems can help all stakeholders (creators, backers, media and investors) reach their respective goals, and bring more ideas to life!

The authors would like to thank Bunnie Huang, Evegeny Lazarenko, Matthew Witheiler and Zach Suppala for their contributions to this article. Applications for HAX 6 are open until mid-November, with up to $100k in funding. The world’s first “inactivity tracker” DARMA targeting office workers is live on Kickstarter. It is a HAX 4 graduate and is already 400 percent funded.