It’s an oft-trotted-out tech truism that there’s an app for everything. But when a pitch for a smartphone application for sexual consent lands in the inbox, well yes, it can certainly feel like there is indeed an app for everything.

The thing is, some portions of life function far better offline than on. Or, to put it another way, an app is not always the answer. Indeed, an app might actually just be expanding the problem.

The app in question — which is euphemistically entitled Good2Go — pitches itself as “a simple sexual consent app for iOS and Android phones”.

So simple it doesn’t even use the word “sex” once. You really can’t make that up.

The notion of a “simple sexual consent app” should immediately set off alarm bells, given its oxymoronic feel. If sexual consent boils down to a question with a simple yes/no answer then why on earth do you need an app for that?

And if it’s not so clear cut, well then turning an intimate dialogue between two people into a digital threesome is surely only going to complicate matters further — especially given that usage of a sexual consent app might itself apply subtle pressure for consent when someone isn’t ready or willing to do so. Or indeed if the person changes their mind after previously confirming they were “Good2Go”, as the app euphemistically rebrands sex.

Reminder: No still means no, even if you previously said yes — but now there’s an app that can record and store a prior yes. And where does that leave someone who wants to revoke consent? In a more pressurized place, that’s where — regardless of the app presenting a pop-up warning screen telling users that consent can be withdrawn at any time (which does really rather undermine its entire project of communicating sexual consent via an app).

Illuminating the knots* this app is tying itself in to provide some kind of ‘sexual consent workflow’ is this three minute explainer video — which does a great job of demonstrating exactly how contra-simple the process of using this “simple sexual consent app” is, with multiple choice options, confirmation screens and emails, and a unique code to be inputed by the consenting party. To affirm sexual consent both parties have to have their phones to hand and be registered users of the service. Saying no does not require signing up to the service — but those denying consent are offered the chance to sign up anyway (sex might be off the table but why waste a user acquisition opportunity, eh?).

More importantly the video underlines how problematic the app’s framing is. This is most obvious in the way it reframes the core consent question — which in plain English would read: ‘do you want to have sex with me?’ — as a positive (and non-specific) collective suggestion: “Are We Good2Go?”.

I mean WTF does that actually mean?

You would expect far better use of language from an app that’s purportedly aiming to fix miscommunication.

After this bafflingly vague opener, the “three choices” the app offers the partner who is being asked to consent to sex are also highly dubious — given that they boil down to: no, yes, or yes.

So that’s a ratio of two yeses to one no.

Why not have the third choice phrased as a neutral “we need to talk” — for people who might well want to do more talking before making a yes/no decision either way — rather than the current phrasing which sets up an expectation that indecision means ‘yes with conditions’ (the app’s exact phrasing here is: “Yes, but… we need to talk”).

This ‘yes majority’ ratio on the core consent question is pushing the partner who is being asked to consent in the direction of sex because the app is skewed in the direction of consent.

Neutral? Not so much…

If a partner does give consent the app then opens a massive can of worms by embroiling itself in the thorny dichotomy of consent vs intoxication.

After a user has confirmed they are “Good2Go” (i.e. digitally agreed they will have sex) it then asks the consenting partner to assess their own sobriety level — including offering an option whereby they confirm consent even if they consider themselves “intoxicated”. So the app is basically telling a drunk person that they are still sober enough to have sex. And apparently normalizing giving (and getting) consent from an intoxicated person.

Again the majority of the options at this point in the app (three out of four) skew towards consent — with only “pretty wasted” being judged by the app makers as too drunk to consent to having sex. (So if the user selects “Pretty wasted” it disables their ability to consent, saying they are too wasted to do so.)

Asking a drunk person to assess how drunk they are is both a fool’s errand and hugely irresponsible. Because the thing about intoxication is, y’know, it temporarily removes a person’s ability to make sound judgements about things like their sobriety level. But hey, the app says I’m sober enough to have sex so it must be true!

Given the app makers’ positioning and marketing of Good2Go as an anti-sexual assault aid — they are specifically targeting US college campuses (and colleges are of course places filled with plenty of sexually active intoxicated people) — it’s mind-numbingly irresponsible to muddle intoxication and consent in this way.

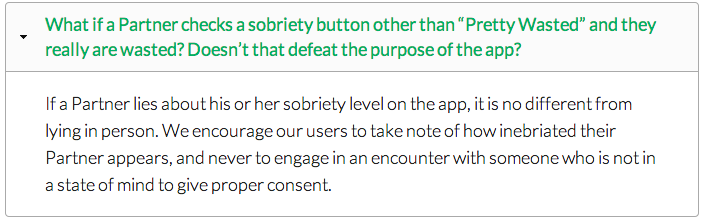

The app maker’s own FAQ also contains the below headscratcher of a paragraph — which appears to suggest that a drunk person who is too drunk to consent to sex is not too drunk to fashion a ‘lie’ about their own sobriety level. Again, terrible choice of language by an app that’s supposed to be facilitating clearer communications…

Really, as one of my TC colleagues said on seeing the Good2Go app, this has to be a joke. Except, apparently, it isn’t. The app is live on the App Store and Google Play.

The developers behind Good2Go claim to have positive intentions — at least their video talks about wanting to “prevent or reduce sexual assault, miscommunication and regretted activities”. Which is of course a laudable aim. But it’s not that aim that’s the issue here — it’s how they’re going about it.

If — for instance — they’d made an app called ‘Let’s talk about sex’ — which generated funny conversation starters to help you casually kick off a discussion with your S.O. about doing the do and stuff that turns you on or off, then a claim about working to improve sexual communication might look more credible, because the app would actually be getting the two people involved talking generally about sex (not just focusing narrowly on the issue of consent).

But that’s not what Good2Go does. It has a different agenda which explains why it’s skewing towards encouraging consent.

Digging deeper into their FAQ it becomes evident why the app skews this way: it’s explicitly aiming to act as a safeguard for men who initiate sex in a situation where they might fear being accused of assault. Such as when treading Good2Go’s blurred line of intoxication, presumably: “The app is designed with two main goals in mind. One is to protect the Partner from doing something she would be uncomfortable with, and the other is to protect the Initiator from later being unjustly charged with sexual assault.” [emphasis mine]

So, just in case you were in any doubt about it, this is an app for dudes who are asking women — and in all likelihood intoxicated women — to consent to sex. Dudes who, in addition, might be worried that their sexual behavior leaves them open to accusations of sexual assault or rape. Which does rather explain the app’s problematic framing.

An app offering a workflow for sexual consent is already a problematic idea — given how an ill-thought-through structure can easily pile pressure on sensitive discussions. But throw in positive bias towards guys wanting a helping hand to more easily procure consequence-free sex with somewhat drunk women and, well, it’s practically toxic.

Yes, unfortunately, there is now an app for that.

So Good2Go? No, just no.

(*A third knot to consider here is that users of this app are providing a detailed log of exactly who they have and have not had sex with to a third party entity — for free. Truly we live in public.)

[Image by Nathan Gibbs via Flickr]