Curse CEO Hubert Thieblot moved his company headquarters to “Rocket City” Huntsville, Alabama from San Francisco last year.

When Curse CEO Hubert Thieblot told his employees last year that he was moving the company’s San Francisco headquarters to Huntsville, Alabama last year, they thought he was crazy.

About 20 of his employees quit because they didn’t want to relocate.

“It was very controversial,” said Thieblot, who had lived and run the company out of San Francisco for at least five years. “A lot of people did not like me for that decision.”

But today, the profitable, 110-person person company operates out of an Alabama city with a population of just under 200,000 people and the highest number of Ph.Ds per square mile given Huntsville’s history with NASA as the nation’s “Rocket City.” Curse just closed $16 million in funding earlier this week too from the China-centric venture firm GGV Capital.

“If you want to build a long-term company, you might have a better chance of keeping people outside of San Francisco,” Thieblot said. “The job market is too crazy here.”

Indeed, the cost of living and commercial real estate is also pricing smaller startups out of San Francisco. I’m seeing bootstrapped founders, who have yet to a take full round of funding, trickle into surrounding cities like Oakland, Daly City and the Bayview neighborhood of San Francisco, if they’re not considering urban hubs in other parts of the country altogether.

Jon Wheatley, a British entrepreneur who co-founded DailyBooth, wrote a good post about this when he decamped for St. Louis, Missouri to dream up new projects.

“If you’re trying to bootstrap, being based in San Francisco is awful,” he said. “The leading cause of startup death is running out of money. Moving to a cheap city and doubling (or more!) your company’s runway will more than likely vastly increase your chances of eventual success.”

Are we supposed to cry for these entrepreneurs, like the teachers, public servants, artists and the elderly who have already faced several decades of gentrification in San Francisco?

Um, no. Not really.

From a national perspective, it’s a good thing to see these job opportunities become more geographically diversified. (I mean, did you see the first quarter U.S. GDP numbers?! The economy contracted at an annualized pace of 2.9 percent.)

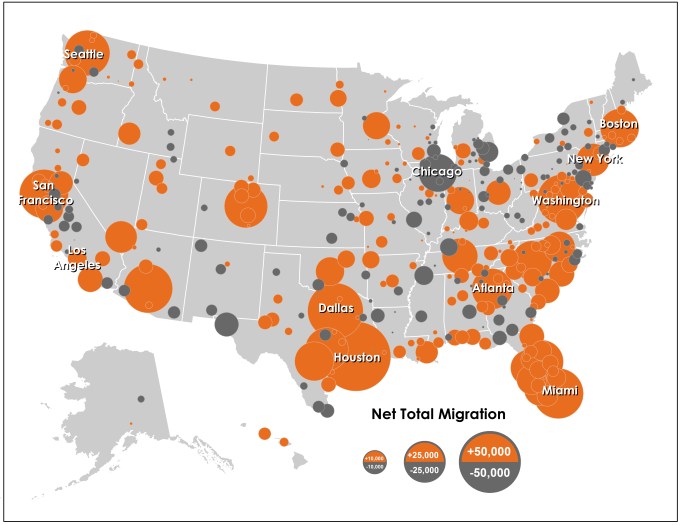

From 2012 to 2013, San Francisco experienced strong in-bound flows of both domestic and international migrants. The city grew by more than 30,000 people to a population of 837,442 last year.

While the rest of the country is only starting to see the kind of job recovery that may make the Federal Reserve finally raise interest rates later this year, the San Francisco Bay Area is bursting at the seams.

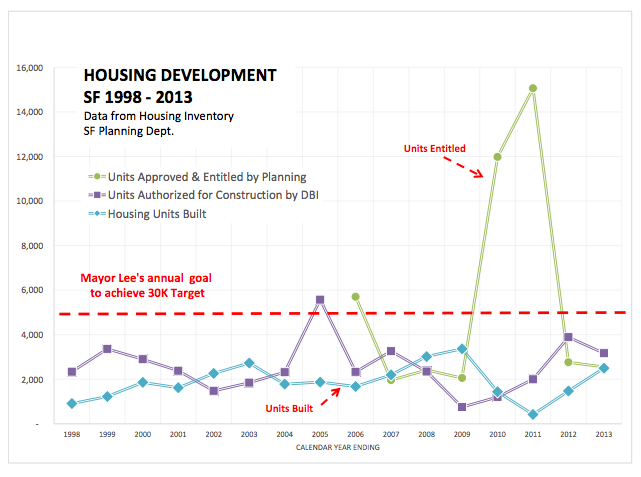

The city is at its highest employment levels ever and the population is expected to reach 1 million people by 2032. The city grew by 32,207 people between 2010 and 2013, but only added 4,776 housing units in the same period. Hence, our housing crisis.

But we won’t be building enough housing anytime soon. That spike in units entitled is from large projects like Treasure Island, which may take decades to appear. We’re supposed to be doing 5,000 units a year to meet Mayor Ed Lee’s housing goal, but that’s more than the city has produced in any single year since at least the 1960s.

Similarly, commercial rents are nearing dot-com period highs. The Information reported last week that the average price per square foot for so-called Class A office space in San Francisco is $64.45, just shy of the dot-com bubble peak of $67.20 in the third quarter of 2000.

Commercial real estate developers are all scrambling to get their projects entitled as quickly as possible before they run into a nearly twenty-year-old San Francisco law called Prop M, that caps the amount of office space that can be built in a given time period.

Many startups are coping by operating distributed teams, with one founder here in Silicon Valley and another working with engineers in a different part of the country (or world).

Jason Citron, a veteran founder who sold OpenFeint to GREE for $104 million two years ago and is backed by Benchmark in his new hardcore tablet gaming company Hammer & Chisel, works in Burlingame while his co-founder Brandon Kitkouski is based around Dallas.

“His family’s in Texas. He’s got a nice house. If he had it in the Bay Area, it would cost millions of dollars,” Citron said. “He was commuting for awhile, but that was hard. The Bay Area is at capacity. It’s freaking expensive.” (And by the way, why is housing affordable in Texas? Houston had more housing starts than all of California in the first quarter of this year. Am I saying we should be Houston? No. I’m just pointing out policy trade-offs.)

Similarly, Jen Lu, who started YC-backed toy company ZowPow, splits her startup between San Francisco and Portland. Her co-founder Brian Krejcarek moved back to Oregon after living in San Francisco for many years.

“It’s been a good thing for us,” she said. “We’ve been looking to hire engineers and it’s just really hard to do it here because it’s so competitive and expensive. But he has a network and is able to find talent there.”

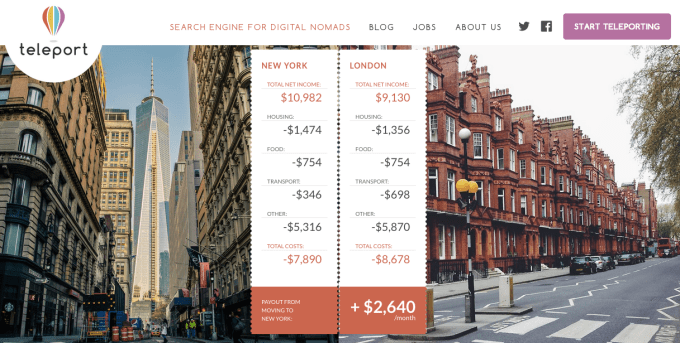

Andreessen Horowitz is incubating Teleport, a “search engine for digital nomads” that helps knowledge workers maximize their quality of life through re-location.

Some of the Valley’s best-known investors are also encouraging geographic diversification. Andreessen Horowitz is incubating a startup called Teleport, which will help knowledge workers improve their quality of life by moving to places that maximize the difference between their cost of living and take-home pay. Marc Andreessen recently published an essay in Politico, arguing that other regions across the U.S. should remove regulatory hurdles around specific technologies they want to attract — be they self-driving car, stem cell or Bitcoin-related startups.

Is this bad for the Valley over the long-run?

Between giants like Google, Facebook and Apple and then later-stage companies like Uber, Square, Dropbox and Twitter, the region has a healthy mix of employers.

Yet the heated real estate market favors capital-rich, growth-stage companies right now, often at the expense of other kinds of creative experimentation, be it a longstanding artist’s collective or a not-yet-Ramen-profitable entrepreneur. The cost of living and the competition for talent simply doesn’t give startups a lot of time to find product-market fit here unless they’ve raised a lot of capital.

In contrast, Google, founded in 1998, and Facebook, founded in 2004, came of age when the Valley was weathering slower economic times and it was easier and cheaper to form a cluster of AAA technical talent inside any single company.

Is that worrisome? Maybe a little. When you look at other cities that have historically been dependent on a single industry like Detroit, the population declines started after power consolidated to a handful of companies like GM, Ford and Chrysler, which then began distributing their plants around the country in the 1950s to avoid the risk of production disruptions from worker strikes. (These changes predated competition from Asian auto manufacturers by at least a generation.) Ideally, you want a mix of firm sizes, and younger and older companies.

But ultimately, these things come and go in waves, and the Bay Area is an undeniably attractive place to live no matter what. A decade ago, the world’s leading mobile OS was built out of Helsinki by Nokia. Today, both of the world’s leading mobile OSs, Android and iOS, are here in Silicon Valley.

Cities have to maintain a certain equilibrium between people moving out and people moving in. Right now, the escalating costs and sheer limits of Bay Area’s housing and transit infrastructure are tilting that balance back out to the rest of the country.

So if you’re a mayor of another U.S. city and you want to attract jobs, now would be a good time to drop by a Y Combinator or 500 Startups demo day to make a pitch.

We have our hands full.