Unfortunately, there is no app or API that can solve San Francisco’s housing and commercial real estate crunch. It’s rather complicated.

But there is this other retro, 2,500-year-old technology that might work.

It’s called voting.

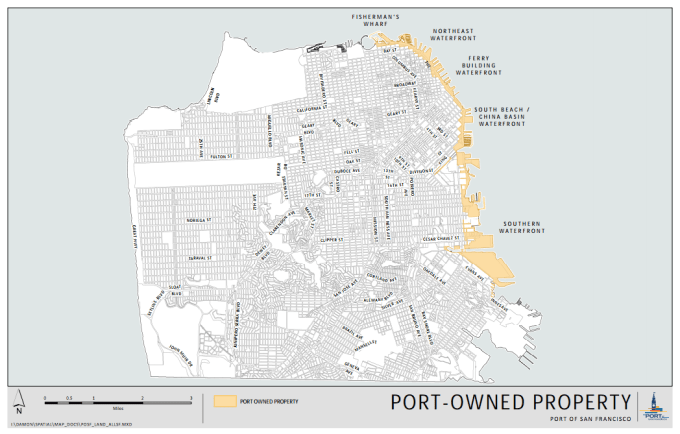

I’ll drop the patronizing tone. But today, there is a proposition going to ballot that will compel the entire city to individually vote on new developments if they exceed current height limits on much of San Francisco’s waterfront (pictured above).

The practical impact would be a chilling effect on development across the city’s waterfront in the midst of one of the worst housing crises that San Francisco has ever seen.

Given a low turnout June election, it was widely expected to pass. So no one from the mayor to the city supervisors really wanted to touch it. But something happened in the last few weeks as voter polls showed the race narrowing with 33 percent ‘No’ votes to 31 percent ‘Yes votes.

Proposition B sounds nice on paper. Let the people decide! No wall on the waterfront!

But in practice, it adds political uncertainty to an already sophisticated process, raising costs for final buyers or dissuading developers altogether. Much of the port lands covered by the proposition are zoned for 40-foot height limits. (That’s shorter than the Ferry Building.)

The Port of San Francisco found in previous studies that low-rise development at around these heights wasn’t economically feasible. Plus, the port also already has $1.5 billion in unfunded infrastructure needs, so where is that capital going to come from?

While I understand that the waterfront land is precious and that land use mistakes cannot easily be undone, the city has already developed a very participatory process involving commission hearings, neighborhood meetings, professional city planners and the Board of Supervisors that has taken decades to develop. Regular voters are not steeped in understanding how to measure environmental impact or gauge infrastructure fees, and the planning department is concerned that whatever new regime arises from the proposition would let developers bypass otherwise mandatory environmental reviews. (You can read a longtime architect’s take on it here.)

Furthermore, I am concerned that if it passes, the handful of people behind it — Aaron Peskin, Jon Golinger (who made a mockery of the ballot argument process earlier this spring) and the wealthy couple Richard and Barbara Stewart (who largely funded it to protect their views) — will be emboldened to push for initiatives covering other neighborhoods of San Francisco, which will further strangle what is already one of the most complex and deliberative planning processes in the country.

The NIMBYist, wealthy voting classes of the peninsula and San Francisco have not added homes in line with the region’s job growth. So we are embroiled in a brutal, practically one-in, one-out battle for the city’s very limited housing stock, which is creating pressures for evictions among the San Francisco’s elderly, disabled and working-class residents.

Between 2010 and 2013, the city grew by 32,207 people but only added 4,776 housing units. For an inside look at how these battles play out parcel by parcel, you can read this depressing first-person take from Bernal Hill where neighbors are battling it out over an undeveloped lot.

Like other global cities, San Francisco faces the twin challenges of urbanization and rising income inequality. Like other American cities, it has to face these problems largely alone, after cuts to the federal Housing and Urban Development budget over the last 30 years and the dissolution of the California state redevelopment agencies. The city subsidizes the construction of new affordable housing through market-rate developments, and if you want to bump the allocation for affordable housing higher, you’d probably need to allow more density or height to make the numbers work. So additional restrictions would chill housing production and rehabilitation for multiple income tiers.

We must ask ourselves: If not here, then where? If the peninsula suburbs and the city cannot make room for more homes over the next five to 10 years, the spillovers will continue into Oakland and potentially accelerate displacement of the East Bay’s historic black communities, which have already dealt with decades of disinvestment and redlining.

In the face of broad, regional population growth, San Francisco’s culture and attitude around re-development needs to fundamentally change. That can only happen through the electorate.

For real change, the political bodies of the city need to hear from a broader swath of the tech community.

And that means you.