The U.S. smartphone market remains quite peculiar. Despite a plethora of inexpensive models from other companies, Apple and Samsung remain the dominant manufacturers that collectively take about 68 percent of the market and whose iPhones and Galaxies are among the most expensive options available.

And they aren’t just getting affluent consumers to purchase them. As NPD Group data shows from 2013, iPhone sales grew 64 percent among consumers with incomes below $30,000.

One reason for this sales growth is that both companies have provided consumers with more affordable options, either by introducing new models or cutting prices on existing ones. Apple continues to sell the iPhone 4S, which today is $450 unlocked. Samsung has an extensive line of affordable phones whose sales represented close to two-thirds of the units sold by the company, although many of these sales happened in markets outside the U.S.

That is only part of the story, though. For years, both companies benefitted from a combination of wireless carrier subsidies, atrocious substitutes, and network effects that brought consumers to them in droves. But the market is continuing to evolve, and all three elements are changing in directions that will place new pressure on high-end phone manufacturers to compete effectively.

The Growing Cracks in Wireless Carrier Subsidies

For years, high-end smartphone manufacturers like Apple and Samsung benefitted from a crooked subsidy in America.

Mobile service operators like Verizon covered the cost of a high-end device as part of their standard phone plans, allowing customers to pay about 25 percent of the device’s true cost (roughly $200 for entry-level models), and pay the balance over the course of the two-year subscription. Everyone was required to pay for this subsidy — even customers who brought their own phones to the carrier and received no benefit.

Since plans are the same price, consumers are incentivized to buy their devices through a carrier contract. Entry-level phones were free, and high-end devices like iPhones and Galaxy devices generally started at $200. Given the minimal cost difference, it is unsurprising that many consumers decided to splurge for the better options, making high-end phones the dominant purchases in the United States.

That egregious system is changing, and with it, the protected business models of the top-priced device companies.

Last year, America’s fourth-place carrier, T-Mobile, announced a new marketing campaign around a concept it called the “uncarrier.” Among the many improvements the telco initiated was the decoupling of phone and data service from mobile device subsidies. Customers can now purchase just a service plan, and then choose to additionally finance a new phone over a two-year period. A consumer can spend $100 on an entry-level phone or pay $27.50 per month for 24 months (a total of $660) to receive a Samsung Galaxy S5.

For the first time, cheap devices are now actually cheap for consumers in America. The range between the top-of-the-line and bottom-of-the-line phones is not $200 anymore, but more like $600 or even $700. That’s quite an increase in choice for consumers.

At least at T-Mobile, that is. Unfortunately, the other three carriers have not followed suit as aggressively, instead offering various programs that essentially act as a discount on purchasing a new device. Their reticence perhaps isn’t surprising – financing the purchase of a phone is as lucrative for Apple and Samsung as it is for the carrier.

Consumers are responding by voting with their wallets, as this last quarter was a strong victory for T-Mobile over the other carriers. Verizon Wireless lost 95,000 net phone subscribers last quarter, AT&T gained a net of 311,000 and T-Mobile added more than 1.2 million net subscribers. Of course, many factors go into the decision by a consumer to choose a particular wireless carrier, not least of which is T-Mobile’s offer to pay the early termination fee of its competitors.

Yet, the fact that any of the carriers are giving consumers choice outside of the narrow expensive phone options of the past is a troubling omen for the manufacturers who have been subsidized by it for years.

Finally, Some Great Mid-Range Phones

This victory has been muted, though, because cheap phones have generally had dramatically inferior hardware specs, software, and design compared to their more expensive counterparts. With the exception of the relatively inexpensive Google Nexus series, consumers have been forced to compromise on the quality of their devices in order to save cash.

But if you read our review of the OnePlus One earlier this week, that is no longer the case. As Darrell Etherington wrote, “OnePlus One manages to do the impossible, offering up top-tier specs at mid-tier prices. It does this seemingly without sacrifices…” Their phone has technical specs that match the leading phones from other manufacturers at a price point of $300.

Over time, inferior products become good enough for many consumers who prefer a lower price over the souped-up products at the high end of the market.

The OnePlus One is certainly not the first smartphone that offers great performance at a fraction of the price. You can get unbranded phones from China at even deeper discounts, and companies like Xiaomi are offering competing phones at the $300 price point. So far, however, these manufacturers have been unwilling to turn their eye to the U.S. market, and instead have targeted emerging economies. That is likely to change as the device subsidy system slowly phases out, and these phones are suddenly deeply price competitive.

For Apple and Samsung, this turn of events is probably the most serious threat to their supremacy in the U.S. market since they introduced their smartphones (this development has already taken place in emerging markets). Their phones are using the same core hardware technologies as devices half their price, and at the same time, consumers may start to feel the full brunt of the additional cost of purchasing an expensive device. Many will continue purchasing high-end models, of course, but now they will have at least some choice on what they want to buy.

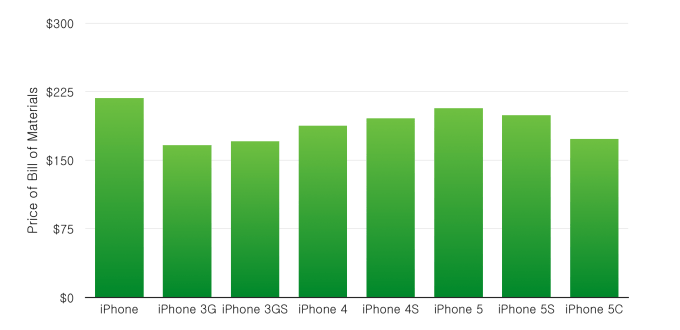

Neither Apple nor Samsung have the necessary cost structures to be able to compete on price. Take a look at Apple’s assumed cost of producing an iPhone. From the original version to the 5s, the estimated bill of materials has barely changed in the last seven years, hovering around $175 per device, according to IHS iSuppli (see the graph below). Even Apple’s lower-cost iPhone 5c has a bill of materials of $173.45, only $25 cheaper than its 5s cousin. That’s just for the parts, though. If we add areas like marketing, distribution, sales, and related expenses (“cost of goods sold”), the total marginal cost per unit approaches $300. Thus, Apple’s profit starts at the price of its competitors’ products.

It’s a classic innovator’s dilemma. The incumbent players, faced with inferior competing products, don’t worry much about the market that they already own. Over time, though, those inferior products become good enough for many consumers who prefer a lower price over the souped-up products at the high end of the market. In such situations, companies attempt to persuade consumers that their products are superior, and thus should command a higher price.

We have seen precisely these moves from Apple and Samsung in their latest releases. Apple focused its marketing around its TouchID system, an easy way to unlock the device without the need for entering a keycode. Samsung emphasized its device’s waterproof exterior and heart rate sensor, features not generally supported on competing phones.

Software, Network Effects, and the Luxury Conundrum

Where Samsung and Apple differentiate themselves is around software. The burgeoning crop of mid-tier smartphones has yet to build a killer device that was complemented by equally well-designed software. As our review on the OnePlus One noted, the version of Android shipped with the device allowed for incredible customization, but at the expense of the simplicity noted in products from Apple and even Samsung.

Beyond the operating system, Apple benefits from its deep library of apps. Developers still commonly launch their products on iPhone first, and the limited number of Apple models ensures that quality control remains simpler than on Android (even with that platform’s device-independent tools). Samsung’s dominant position in the Android market ensures that most apps are tested against its devices, giving its users a great experience.

These are network effects – the more consumers that use a handful of devices, the more likely that developers will build for those devices.

It is a deep mistake to believe that a smartphone, or really any computing device today, could ever truly be a luxury object. Luxury goods are fundamentally about exclusion through price.

Yet, the share of the worldwide smartphone market held by these two companies continues to slide. Startegy Analytics notes that both Apple and Samsung lost market share last quarter, and combined they now represent less than 50 percent of the total market. Even though both companies continue to grow their sales, the overall market is increasing in size much more rapidly, and they aren’t competing effectively in emerging markets.

As WhatsApp showed, there is a lot of money to be made in serving the wider diversity of handsets available outside of the premium market. While iOS has long had a stranglehold on developer revenue (its customers love spending money on apps), this may not hold as true if its market share continues to decline and Android reaches more and more people globally.

One approach is to think of these top smartphones as luxury devices. But it is a deep mistake to believe that a smartphone, or really any computing device today, could ever truly be a luxury object. Luxury goods are fundamentally about exclusion through price. In the right conditions, the demand for a product may be proportional to its price (economists call these Veblen goods), meaning that a product is more desirable the higher its price. This makes sense for fashion and accessories like purses, watches and sport jackets, where functionality matters less than social distinctiveness.

But today’s smartphone consumers demand their devices interoperate and collaborate at all times, making it difficult to create a luxury brand. We want to be able to interact with our friends through applications and share our experiences playing the same games or reading the same content. Due to these fundamental network effects, software is a winner-takes-all system, even outside of areas like office productivity. Consumers congregate in a couple of hit apps, and the long-tail receives scant notice.

That’s why it is a bit disconcerting that Apple hired Angela Ahrendts, former CEO of Burberry, to head its retail operation, ostensibly to provide that elite Burberry touch in each of its several hundred retail stores. While Apple hasn’t moved toward being a luxury brand, it needs to ensure that it doesn’t attempt to move too far upmarket – and suddenly see its market share look more like the Macintosh than the iPhone over the past several years.

The Rise of the Good-Enough Smartphone

The key for analysts then is to watch how consumers adapt to the changing market and see if the high-end manufacturers are capable of responding. Carrier subsidies may just continue as they do today, and thus, there still won’t be competition for consumers. If subsidies do slowly disappear, consumers may continue to choose Apple and Samsung just as they did in the past, and the lower-priced options may never find demand.

But I believe these mid-tier phones are going to be much more compelling than many analysts give them credit. If that prediction proves true, then Apple and Samsung would either have to lower prices and hurt their margins to remain competitive, or attempt to become more upscale in a space where broad popularity is key to attracting the attention of developers. Neither option is compelling, and thus, the next two years will be the era of good-enough smartphones.