The battle to own the digital map continues — with Google stepping up its game in the U.K. today by significantly expanding the transit data embedded within its mapping interface.

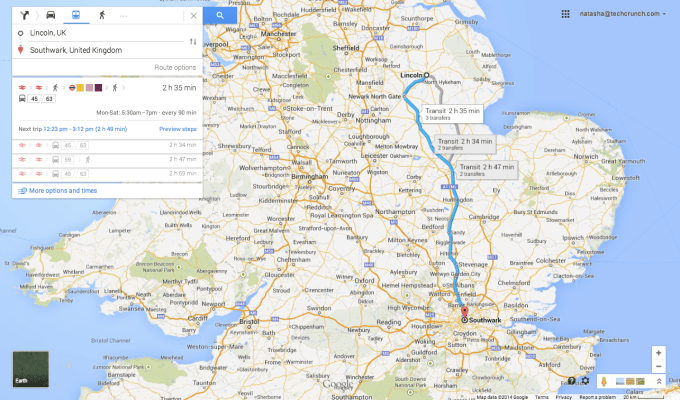

It’s now offering Google Maps users public transport options for routes across the U.K., not just driving or walking directions to get where they want to go.

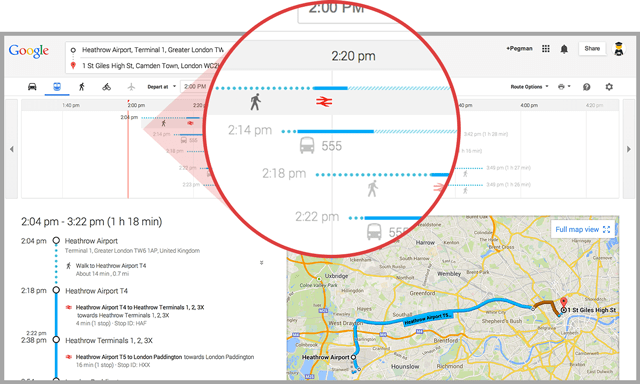

The new U.K. transport data is available across Google Maps for iPhone, Android and on desktop, and allows users to check times and routes for millions of public transport departures across some 17,000 routes, according to the company.

Google was previously offering National Rail Services data and some other public transport options for London and the South East, but has now added data for “every bus, train, tram and ferry across the U.K.” — allowing Maps users to evaluate different public transport options from right within the maps interface.

The data is being sourced from the U.K. public transport data from open transport data organisation, Traveline.

There are various forces at work here, pushing Google to build out the features offered by Maps.

For one thing, journey planner apps have been getting decent traction — such as the urban transport app Citymapper, which took in a $10 million funding round last month — pulling eyeballs away from Google Maps in the process.

After all, what’s the main reason for people to look at a map? To figure out how to get where you’re going. That logic means Google Maps has been losing potential eyeballs to slickly designed mobile apps that focus tightly on helping people figure out the best/fastest/most efficient transport options.

Google will be hoping to rein in that trend by making Maps more useful. Adding public transport options right into the interface — and doing so for the whole of the U.K. — could put Google Maps back in the driving seat for journey-planner based searches that aren’t solely fixed on large urban centres like London.

While Londoners are well served with apps for public transport (and aren’t about to ditch them to wrangle with Google Maps), people living in other parts of the U.K. may not be so spoilt for choice. So there’s an opportunity for Google to make itself stand out as a user-friendly central repository for national public transit data.

Another thread is the increasing number of multi-modal transport startups, such as GoEuro and Rome2Rio, which are making it their business to help users filter the best transport options for a particular journey — looking not just nationally but across borders. Again, these startups have been chipping away at the utility of Google Maps.

And then of course there are the big rival maps to Google Maps — such as Nokia’s Here maps, which has been incorporating transport data for the U.K. for a while, including live data for trains. Or Microsoft’s Bing Maps. Or indeed Apple’s maps.

Apple famously ejected Google Maps as the iOS default back in 2012 — underlining the strategic importance for big tech companies in owning as much of their users’ mapping data as they can.

iOS users can of course still download and use Google Maps as an app, so Google pushing new features into Maps is a way for it to worm its way back into the iOS ecosystem — by outpacing Apple on the new features front. (Apple Maps does not currently include transport data.)

Arguably, though, the really big fight for Google Maps is not against those big rivals with their competing map properties. Rather it’s for all of them to remain relevant as more and more startups start doing increasingly clever things with map data — making the baseline map itself a commodity, even if it has a bit of transport data thrown in.

The bottom line is it’s not the map that matters anymore, it’s what else you put on it that counts.

Startups — like MapBox — are driving more interesting, customised, personalised maps inside all sorts of apps. So that’s the really big war that’s been waged with map data.

Maps have gone mobile on smartphones, and older products like Google Maps that were born in the desktop era are at risk of being overtaken by a proliferation of dedicated apps that fold mapping into their core functionality.

Seen in that context, today’s U.K. Google Maps tweaks could very well just be a finger in the dam. And what started for Google as a nice-to-have 20% time project back in 2005 looks more like a strategic play within a much wider, mobile-powered war.