There is no point in kidding ourselves, now, about Who Has the Power.

— Hunter S. Thompson, jacket copy, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

The Internet wasn’t supposed to be so…Machiavellian.

In 1963, Stewart Brand and his wife set out on a landmark road trip, the goal of which was to educate and enliven the people they encountered with tools for modern living. The word “tools” was taken liberally. Brand wrote that “a realm of intimate, personal power is developing.” Any tool that created or channeled such power was useful. Tools meant books, maps, professional journals, courses, classes, and more.

In 1968, Brand founded the Whole Earth Catalog (WEC), an underground magazine of sorts that would scale in a way no road-weary Dodge ever could. The first issue was 64 pages and cost $5. It opened with the phrase: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.”

A year after WEC’s start, on October 29, 1969, the first packet of data was sent from UCLA to SRI International. It was called ARPAnet at the time, but with it the Internet was born. Brand and others would come to see the Internet as the essential, defining “tool” of their generation. Until its final issue in 1994, the WEC’s 32 editions provide as good a chronicle of the emergence of cyberculture (as it was then called) as you can find.

Cyberculture. It’s a curious and complicated term in today’s society, isn’t it? Cyberculture is at once completely outdated and awfully relevant.

The business of making culture has been for too long now controlled by people who live outside it.

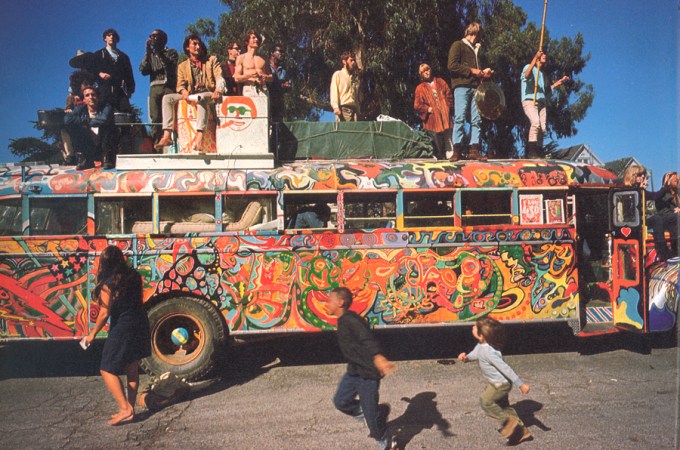

As Fred Turner has argued, Brand is a key figure in the weaving together of two major cultural fabrics that have since split — counterculture and cyberculture. Brand is also immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as a member of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters. And Brand famously assisted researcher Doug Engelbart with the “Mother of all Demos,” the outline of a vision for technology prosthetics that improve human life; it would define computing for decades to come.

The Merry Pranksters, still from the movie Magic Trip

Brand attended Phillips Exeter Academy — an elite East Coast high school, and an institution of traditional power if there ever was one. He was a parachutist in the U.S. Army. He graduated with a degree in biology from Stanford, studied design at San Francisco Art Institute and photography at San Francisco State. He also participated in legal studies of LSD and its effects with Timothy Leary.

That’s hardly the typical resume of a technologist or an entrepreneur or an investor. But it should be. The business of making culture has been for too long now controlled by people who live outside it.

It is my opinion that the Internet of today can and must be countercultural again, that cyberculture should — needs to be — countercultural.

That word, countercultural, carries with it the connotation of liberal idealism and societal marginalia. Yet, the new countercultures we’re seeing online today are profoundly mainstream, and drawn along wholly different political lines. The Internet is its own party. The Internet has its own set of beliefs. Springs have sprung the world over and this isn’t simply a nerd thing anymore. We all care passionately about Internet life and Internet liberty and the continual pursuit of happiness both online and off.

Yet if the Internet is a measure of our culture, our zeitgeist, then what does it tell us about the spirit of this age? Our zeitgeist certainly isn’t what’s trending; it’s not another quiz of which TV character you are; it’s not another listicle. I changed the global power structure and all I got was this lousy t-shirt. And Facebook. And Twitter.

What is this generation’s Rolling Stone? What is our Whole Earth Catalog? It’s an important question because if the Internet is defining our culture, and our use of it defines our society, then we have a responsibility to ensure and propel its transformative impact, to understand the ways cyberculture can and should be the counterculture driving change rather than just distracting us from it.

There are beacons of hope. I eagerly await Jon Evans’ fantastic column in these pages each weekend for reasons like this.

The Daily Dot, a publication I co-founded, documents today’s cyberculture through the lens of online communities — virtual locales in which we arguably “reside” more deliberately than any geography. You should also be reading Edge, N+1, and Dangerous Minds. Even Vanity Fair has turned its eye to this theme, successfully I think, with articles like this. Rolling Stone is doing a pretty good job of being Rolling Stone these days, too.

I’m terminally optimistic, and I believe that counter-cyber-culture is inherently optimistic, as well. Even despite the U.S. government’s overreaching on privacy and “protecting” us from data about our own bodies, despite Silicon Valley’s mad rush to cash in on apps rather than substantial technology, despite most online media’s drastic descent to the lowest common denominator and even lower standards of journalism, I remain…optimistic.

We have found a courage in our growing numbers online. People old and young can be be bold and defining on the Internet, underwritten by the emotional support of peers everywhere. We’re voting for what we want the world to be, and how we want it to be. Why do you think Kickstarter works so well? We fund things that without our help are unlikely to exist, but ought to nonetheless. Our “likes” and “shares” are ultimately becoming votes for the kind of future we want to live in, and I’m optimistic that we will ultimately wield that responsibility with meaning and thoughtfully.

I hope we can manage to be politically aware and socially responsible in a way that technology begs us to be, without giving ground to the idea that the Internet is anything but <i>ours</i>.

Tumblr. 4chan. Etsy. YouTube. We have emigrated to these outlying territories seeking religious freedoms, cultural freedoms, and personal freedoms alike. We colonized, and are still colonizing, new environs each day and every week. We claim and reclaim the Internet like so many tribal boundaries.

We’re winning more often than not, thank goodness. Aaron Swartz heroically beat SOPA and PIPA against all odds. Yahoo won against PRISM. The Internet won against cancer…with pizza. My godmother knows what Tor is.

The virtual reality community rebelled when princely Oculus sold to Facebook, for the reason that VR is a new superpower and a new countercultural medium that we’re afraid might have fallen into the wrong hands (I don’t believe that’s actually the case, but that’s grounds for another post altogether).

So, yes. A countercultural moment all our own stares us in the face. Like Brand, I hope we can manage to be politically aware and socially responsible in a way that technology begs us to be, without giving ground to the idea that the Internet is anything but ours.

Civil disobedience is a different game when the means of production and dissemination have been fully democratized. We seek differentiated high ground from which to defend our values. We build new back channels to communicate unencumbered. Instead of making catalogues, we make new categories. We wield technology, perhaps unaware on whose shoulders we stand, but at the same time free from the anxiety of influence.

We aspire to be more pure in that sense. We want and we give and we need and we will have…pure Internet.

Editor’s note: Josh Jones-Dilworth is a co-founder of the Daily Dot; founder and CEO of Jones-Dilworth, Inc., an early-stage technology marketing consultancy; and co-founder of Totem, a startup changing PR for the better. Follow his blog here.

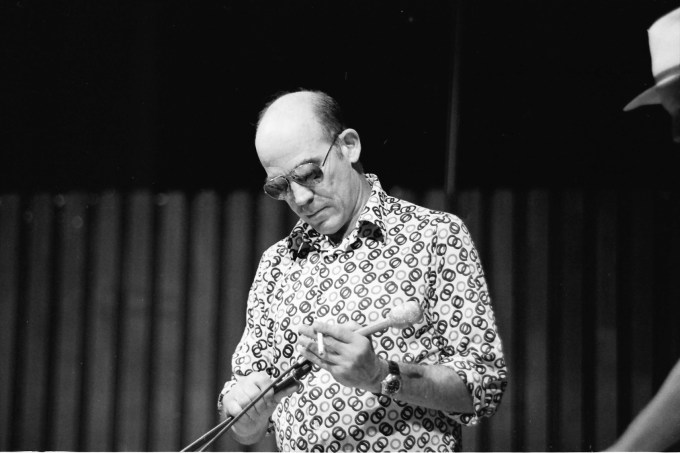

Featured image by Kundra/Shutterstock; Hunter S. Thompson image by Wikimedia Commons user MDCarchives (own work) under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license