N

okia is preparing to become a very different animal. The company whose name is still synonymous with mobile phones in certain parts of the world will — barring a last-minute bout of nerves from the company board — hand off its devices & services unit to Microsoft early next year in exchange for $7.2 billion. Which means that in 2014 Nokia is going to have both the time and the money to refocus its efforts elsewhere — and one key area for the future of the company, indeed one of only three remaining business units at Nokia, is maps & location services, under its HERE brand.No surprise, then, that Nokia is revving up its engines in the location space. Notably, it’s fully integrated the digital mapping giant Navteq — which it acquired way back in 2007, but was running as an independent business up until last year.

On its earnings conference call last month it also talked up the prospects for HERE to compete with Google Maps, and win new business in consumer facing use-cases such as on mobile devices. It’s also revving HERE’s engines literally, with a plan to triple the number of cars it has wearing down rubber mapping new roads and places, and doing the ongoing map maintenance required to keep the data fresh.

Nokia’s HERE business sub-divides into three main divisions — its consumer-facing offering (of which Microsoft is among its top three customers); a b2b/enterprise play, where it works with customers such as Oracle, by, for instance, helping them track their flow of goods to better understand their own businesses; and a very big automotive business, built upon its Navteq acquisition and its turn-by-turn navigation specialism.

The automotive segment is currently the largest of HERE’s divisions — as you’d expect, given how much Nokia spent on buying its way into the market when it purchased Navteq, for $8.1 billion. Globally, four out of five cars with dashboard navigation are using Nokia’s maps. (“Basically every major car company is working with us, at some level,” it says.)

Across all HERE’s division, Nokia’s maps licensing and location data platform business has “hundreds” of customers.

From static to suggestive

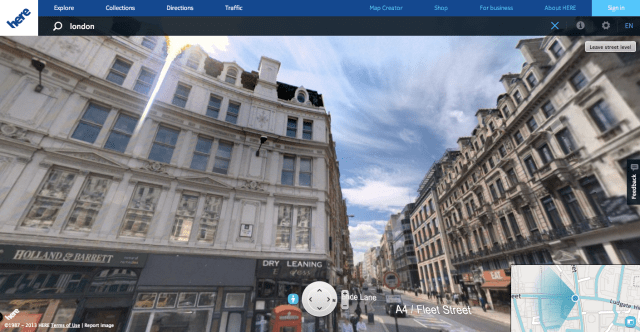

This week Nokia was showing off one of its new-look HERE cars, pictured above, to U.K. journalists, giving live demos of the street-level mapping technology. The flagship tech on show here is the 3D mapping technology it acquired from Earthmine this time last year. Nokia is using this to compete with Google Street View in urban areas but also, more broadly, as the foundation for evolving HERE beyond the legacy Navteq specialism of turn-by-turn navigation.

Building more dynamic and interactive 3D maps is where Nokia sees the future for HERE, says Stuart Ryan, director of Maps and Everyday Mobility at Nokia. A smart, personalised, context-aware location cloud platform may also represent the future for Nokia’s business, post-mobile phones.

It’s about trying to reinvent and redefine the whole concept of what it is to see and visualise and interact with a map.

What kind of maps is it aiming to build? “Immersive, living, rich” maps that draw on multiple content sources and applications and change based on context, or display data in new and playful ways, says Ryan. Maps that also “know and understand you, and suggest things for you”.

“Maps behave, react, inform in a way that’s very, very relevant and personal to you,” he tells TechCrunch. “The challenge our boss gives us is redesign the maps experience for consumers.”

One example he brings up to illustrate Nokia’s thinking here is map of a city that’s transformed from being a realistic digital representation into an abstracted data visualisation that emphasises certain characteristics of the city’s makeup, and/or creates something that looks visually arresting, and is even purposefully un-map-like.

Another scenario he talks about is when visitors to a city want to know where local equivalents for places in their home town can be found — so, in other words, they’re after a map that can show them where “the uptown version of Chicago in Berlin is”, for example.

“It’s got to go from being a very largely static experience, granted built on turn-by-turn navigation, into a much more interactive and suggestive type of experience,” he says. “That’s where it’s going.”

Nokia’s Earthmine vs Google Street View

It was too dark in London’s low-light winter environs to take the HERE car for a spin when TechCrunch checked it out, but the driver showed the system working in the garage. Nokia’s Ryan was also on hand to answer questions.

Nokia’s HERE fleet is not doing all the mapping itself. The company has multiple sources for its maps, and even obtains some mapping data via community (crowdsourcing) contributions to augment the rubber on the tarmac approach, although Ryan stressed that it has teams checking mapping data submissions to ensure their quality, where possible. It also draws in other third party sources, such as data from government agencies.

The HERE car driver showing off the kit inside the demo car had recently been mapping the North East of England, and said he’s typically out from 7:45 a.m. to 3:45 p.m.-4:45 p.m., depending on weather and light conditions. He typically covers around 200 miles a day.

The hard drive in the car — which was sited on the front seat, inside the processing unit — holds a terabyte of data. After around a week’s worth of driving 64% of it had been filled.

The HERE car’s modular rig, which is mounted on the roof, contains a LiDar sensor which captures the 3D data — grabbing objects and textures as the car moves along the road — by sending out signals that bounce back to build up a “3D point cloud”.

“This is what creates a 3D digital representation of the world around us,” says Ryan. “It’s all managed as an X, Y, Z point so we have the location and height information… It’s similar to laser and sonar, those kinds of technologies. It’s based on light pulses and then when it comes back in we just store the location. And we create a composite view, then, of the real-world in a 3D construct. ”

Here’s an example of the street level imagery being captured by Nokia’s rig:

And while, on the surface, Nokia’s street level view may look much like Google’s Street View, Nokia argues that because its technology captures 3D data rather than just taking static photographs, it offers a superior foundation for transforming the basic digital map canvas — by allowing for both new types of content and new ways of interacting with maps to be introduced.

“A static image product has a lot of limitations in terms of the utility it provides,” says Ryan when asked how Nokia’s tech stacks up against Street View. He also says the imagery captured by Nokia’s cameras is “higher accuracy, higher resolution, higher quality” than Google’s Street View cameras, adding: “Which is part of the reason why we invested in the Earthmine technology”.

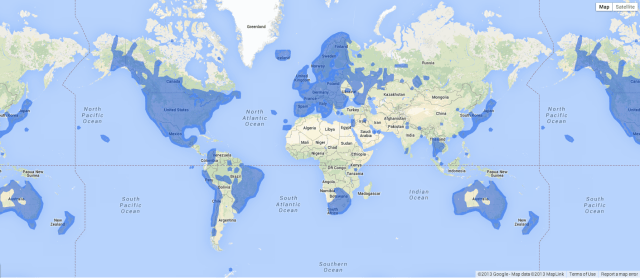

What he’s not so quick to point out is that Nokia’s street level mapping coverage is far less comprehensive than Google’s Street View — Nokia is focusing street level mapping on metropolitan and urban areas, whereas Google, with five+ years of rubber in the game already, generally prefers to cover whole countries, as the below coverage map illustrates:

So when Nokia says it has mapped close to 200 countries, it’s talking specifically about road-level mapping, not the street level 3D data. It’s unclear exactly how extensive Nokia’s street level mapping is at this point — Nokia has previously said the HERE cars will be visiting 27 countries this year — but even in Europe and North America where Nokia kicked off its 3D mapping effort coverage is selective, targeted on urban centres.

Nokia justifies that selective coverage by arguing that street level mapping is more relevant to urban areas where population density is highest — so, in the short term at least, HERE’s Earthmine technology looks set to snub the roads less well-travelled.

But if you can’t compete on quantity vs your biggest rival, there’s always quality. And/or doing something new and different.

Maps that push and pull

“Our team is looking at the utility around how do you make the map more living, more real, more relevant to people — in terms of being able to provide more detail, and make the panoramas around you and buildings around you more relevant in terms of if you think about orientation and guidance,” says Ryan.

“But also… this [Earthmine technology] will allow us to make the map in and of itself more of a canvas and an interface — so we want to get away from the legacy of put something in a search box or a text box and actually scroll the map, select objects on the map, make them reveal things to you and go from there.

“Because everything we have is actually a data model, and not a static image, that allows us to do an awful lot of these use-cases.”

Introducing new “use-cases” to its maps is on the cards for Nokia “later next year”, according to Ryan. Fleshing out those use-cases a little further he lists the following: “truer 3D rendering of what’s around you; making things much more interactive; allowing for certain things to render in certain ways — they could be very, very detailed, or they could be a little bit more occluded”.

Another feature he discusses is transitions — i.e. being able to move map users through a 3D view that takes in aerial imagery and moves down through different levels of detailed 3D content, before they arrive at street level. The aim being to wow users, with both the design and the feel of moving around the map.

He also talks about allowing users to explore cities via maps in a more tactile way using a 3D mapping canvas that lets them touch a building to see what it is, rather than having to type something into a text box or click around on rails. “You don’t click an action to route to… you just click on the building itself to route to,” he explains.

The HERE car’s modular mapping rig could also potentially be attached to other types of vehicles, according to Ryan — even something that’s airborne. “If there’s a way that we can find to mount this technology on the right kind of vehicle, can we also capture aerial imagery? Can we do other things as well? So it’s extensible in terms of how we can use it.

“Our view is on this you differentiate on this more through actually making richer, deeper, interactive, immersive experiences with the map and really evolve how people think about a 2D or a 3D map. That’s the aspiration for us,” he continues.

“It’s about trying to reinvent and redefine the whole concept of what it is to see and visualise a map, and interact with a map. That’s what no one has solved so far.”

From HERE Cars To Driverless Cars

As well as the LiDar sensor, the rig on Nokia’s HERE cars carries a GPS sensor, and a Street View-esque camera that snaps the view from four sides so it can piece the visual scenery back together with the 3D mesh to colour in that data.

The other sensor on board the rig is called an IMU — aka an inertia measurement unit — which captures detailed road characteristics, such as the degree of incline or bend, which Nokia then sells back to customers in the automotive sector to improve their own in-car systems.

“This is a very automotive-centric sensor,” says Ryan of the IMU. “So it’s got an accelerometer, gyroscope, it helps understand direction of travel, velocity of the vehicle, but also very, very important for understanding things like slope of a road, curve information, gradient, for products and use cases around ADAS: advanced driver assistance systems.

“So when you think about things like lane departure warnings, adaptive cruise control, curve warnings and use cases around fuel efficiency and route optimisation — and in essence building the foundation for how we think about automated or autonomous driving, that’s one key thing that a sensor like this contributes.”

Nokia announced a partnership with Mercedes-Benz back in September to work on developing driverless car technology, noting at the time:

The requirements put on maps by autonomous driving go beyond what has been available until now. The very exact precision of lane width, road sign locations and other road network attributes are all crucial components needed to provide routing for autonomous vehicles. This is an area Mercedes-Benz and HERE will continue to explore together, as automakers and HERE spearhead the innovation for future commercial autonomous vehicles.

There’s no time-frame on when such a car could make it to market — and in any case, the technical challenges of building self-driving cars are matched by huge legal and regulatory hurdles that stand just as tall, if not even taller barriers to commercialisation. So developing guidance systems to help steer self-driving cars is definitely a long-term play for Nokia; the road HERE’s automotive business unit may ultimately end up travelling along one day.

In the meantime Nokia sees plenty of areas where it can more gradually extend the HERE platform’s capabilities in the automotive sector — so that it gets even smarter about assisting drivers by collating and redistributing more relevant real-time data.

“There’s a number of projects and discussions we’re having with major OEMs, major car companies around this,” says Ryan. “A lot is happening in that area. Basically as all of these sensors [on the HERE car], plus potentially other sensors within the vehicle, continue to tag and have user information we can use that to feed back to a platform or service… and be able to aggregate that and deliver that back in the form of some value-add service to people.

“One example… [might be] if you’re on the motorway and a car is 25 miles ahead but all of a sudden its windshield wipers start going, if you could signal that back to a platform, you could signal back to the car behind you that it’s raining ahead. So all kinds of things.”

Of course, that example would require car makers to add the necessary sensors to windscreen wipers. But Nokia has various other data sources feeding into HERE’s network already — such as traffic data from enterprise customers with large delivery fleets, and anonymised data gathered from its own maps and mobile users — which it refers to as “probe data”. (You can bet the deal with Microsoft to buy Nokia’s devices & services division requires that this pipeline of probes remains open to HERE.)

Maps made of multiple data sources

One area Ryan mentions where probe data could be used to augment Nokia’s maps with useful, contextual information is by gathering real-time transit data — i.e. where public transport networks don’t make that data openly available.

“We can build estimated schedules based on the lines, the length of the journey between stops, the speed of the train and then we get timetable data,” he says. “The next thing people want to understand is interrupted service, delays, real-time information for transit as well so getting user feedback for that kind of content is interesting.”

Probe data also feeds back into the HERE business in another way: to help Nokia identify when a new road has been built that it needs to send a car out to map. Or to build “heat maps” of activity based on where people are doing map searches and how they are using other Nokia apps (some of which are available on iOS and Android, expanding Nokia’s reach beyond its own legacy/Microsoft’s mobile platforms).

You could call it Nokia’s very own inner Foursquare.

“We actually use [probe data] on our map assets. You can see how we think about activity heat-maps — where the most interesting places and restaurants and POIs are in a city or an area are,” says Ryan.

Probe data, third party data sources, community-contributions and Nokia’s own Earthmine-equipped cars all feed their intel into the HERE platform — Nokia says it uses 80,000 different sources to layer content into its maps. The blood, if you like, that is being pumped through HERE’s digital veins to animate increasingly dynamic maps.

How competitive that data set is vs the Mountain View-sized hoard that Google’s mapping business rests on top of is of course a key question.

Looking at the competitive landscape

Nokia says it is planning to have a fleet of “hundreds” of HERE cars on the road by the end of 2014. It won’t be more specific about exactly how many cars it has, driving around hoovering up the topology. Google also won’t put a figure on its Street View fleet, saying only that it’s driven more than five million miles of unique road since kicking off the project in 2007.

As with Google’s fleet, Nokia’s HERE cars are driving around all the time — a necessity to keep its maps updated, and also to expand street level mapping coverage to better compete with Google.

This never-ending process is clearly a huge cost base for HERE, along with the unit’s 6,000-strong headcount. Nokia’s operating expenses for HERE were €153 million in Q3 this year, which is small relative to other divisions of the business but bear in mind that those divisions are involved in manufacturing hardware vs HERE being a software-focused unit.

There’s a lot of blood in the water with Google around, and other players as well, but there’s huge upside in terms of where the location area is going — and nobody’s really solved it yet.

Focusing HERE’s street level mapping coverage on cities/towns is one way Nokia can cap the costs associated with gathering the more sophisticated 3D data — while being able to innovate on the technology and software side to produce more dynamic and interactive maps for those urban centres in future. And, so Nokia hopes, steal some of Street View’s thunder.

In the automotive sector, Nokia primarily competes with TomTom right now, although Ryan concedes that Google is looking to get a “stronger footing” in that industry — so there’s certainly a sense that the company is checking itself about getting complacent. And that’s not surprising, given the painful lessons of its recent history. Nokia’s mobile business went from being king of the world circa 2007 to also-ran a handful of years later, having watched Google’s Android platform spread like a pandemic from a standing start in 2008 to the circa 80% marketshare of today.

Ryan is also not complacent when it comes to location startups — name-checking Waze as one example of a startup that managed to build significant momentum, with a crowdsourced traffic data platform, and which was of course ultimately acquired by Google.

“The opportunity for disruptors to come along is to solve that hidden use-case or that unmet need. The company that can combine a lot of what we do, and Google go, and Foursquare do, and Facebook do in a location cloud experience is the winning strategy, and that’s why it’s the strategy that we’re pursuing,” he says.

That means Nokia’s challenge, as a long-time player in the location space, is to take a step back from the turn-by-turn/navigation business it knows so well, through Navteq, and allow HERE to become more mobile and social, to be “more about solving more everyday life problems”, as Ryan puts it. “That is where there is an awful lot of untapped opportunity within maps and location.”

“We recognise there’s a lot of blood in the water with Google around, and other players as well, but there’s huge upside in terms of where the location area is going — and nobody’s really solved it yet,” he adds.

With its phone-making days behind it, Nokia wants to plant its flag afresh on the location map — with a banner that reads not just HERE today; here to stay.