Israel-based startup Scringo, which offers a cross-platform SDK to help developers add social elements such as messaging to their apps to increase user retention and boost in-app engagement, has added a new feature that taps into the consumer craze for stickers.

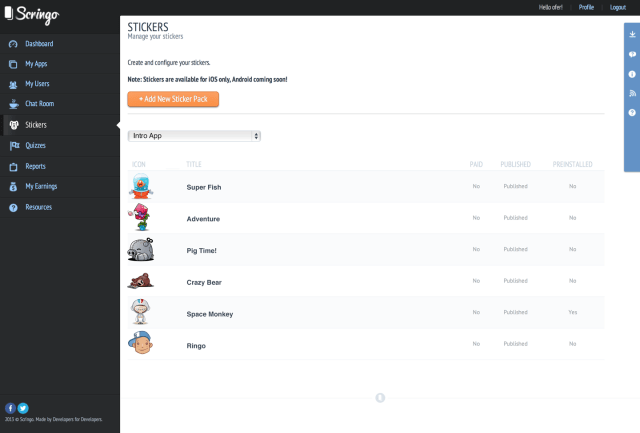

From today, developers using Scringo’s SDK to add social features to their iOS apps (Android support is due soon) will also have the option to add stickers — and even a sticker shop, so they can monetise the addition by selling paid sticker packs to their app’s users.

Selling stickers is a strategy that has worked well for Japanese mobile messaging app Line. Close to a third (27 percent) of its $132 million Q2 revenue came from sticker purchases. And stickers are continuing to spread like a rash across the social messaging space — with everyone from Facebook to MessageMe to Path (to name but a few) seeking to surf the sticky craze. Most to eke out a revenue stream, others like Facebook just trying to keep up with the craze.

Scringo’s platform offers developers a handful of pre-made sticker packs which they can add to their apps as free stickers, or paid packs. The platform also allows them to upload their own sticker designs, so they can customise the content to fit with their specific app.

Scringo is a whitelabel offering, focused on giving developers a hand to expand their feature-sets via the likes of a customisable chat UI. Scringo is monetising its own services by taking a cut of any additional revenues it helps developers to generate. So in the case of stickers, it’ll get a small cut of any sticker sales. It’s the first such monetising feature for Scringo — since its main platform is free.

“I see a very bright future for stickers, and for messaging as a whole,” says Scringo co-founder Ran Avrahamy. “And we have several other in-app features to add to every type of app. We have, maybe going into adding small games into apps. We actually started a couple of months ago… we added a quiz into apps — so any type of app could add a quiz into its app for its users, with leaderboards and stuff like that.

“We will add more and more of these features in the very near future. We have a very clear future — which is trying to utilise every type of app into a social network. And bring in the users… Every type of app or game has the potential of a social network.”

Scringo launched its community and messaging platform back in March, and now has more than 1,000 developers on board. It argues that adding social features enables developers to improve user retention and boost time spent in app.

“What we’ve seen is that utilizing an app’s community potential increases its retention by up to 500%,” he tells TechCrunch, adding: “The users are already in the app, with an obvious mutual interest (at least one) — the only thing an app developer should do, is to allow them to communicate.”

Scringo customers can be developers of any stripes — although there are certain types of apps that make more sense than others. Apps that are primarily social to start with aren’t likely to need Scringo’s feature-set, while certain utility apps may struggle to build a sense of community among users, however hard they try (although Avrahamy says Scringo’s SDK has even found its way into a calculator app).

“Every type of app that doesn’t have the initial intent of being a social network [could add social elements via a platform like Scringo]… We see a huge variety of apps using us. From sports to artists, musicians, entertainment apps. Games that people can talk about a certain level in a game, or characters inside a game. We’re trying to break the industry into sub-categories that can use us, and basically it’s all except social networks and simple utilities,” he adds.

Things are certainly afoot in social. A subtle disenfranchisement of the grand old daddies of the category as more and more mobile apps embed their own social features, giving users alternative channels to ping, prod, poke and message each other. Comms are being routed through many different gateways, splintering the pipeline of social chatter into myriad streams.

Twitter, for instance, cited the new breed of mobile messaging apps, such as Korea’s Kakaotalk, as competitors to its business, in its recent Form S-1 filing ahead of its IPO. It’s fair to say that digital comms tools have never been so diverse. And the risk is death by a thousand cuts to any catch-all social networking service.

Not immediate death, evidently. And likely not complete service death — Facebook will probably always have a place as a mainstream channel for people to post baby photos to and so on. But little packets of user engagement are inevitably being sucked elsewhere, at a rate that’s accelerating as services proliferate and attention fragments across more socialised apps. And of course, the advent and uptake of platforms like Scringo — that make it even easier for developers to ‘socialise’ their apps — is only going to accelerate this fragmentation.

In terms of competitors, Avrahamy argues that Scringo is “pretty unique” in focusing on messaging and allowing users to communicate with each other within an app — and because of its grander “mission” of helping developers turn any app into an independent social network. And also because Scringo is addressing both the front-end and back-end portions of development.

But he does name the likes of Disrupt Alum Layer as a rival platform for enabling in-app messaging, along with companies offering “social SDKs” for game apps, such as Heyzap and PapayaMobile. “What we’re bringing is more of a front end, not only the back-end on the stores. So we’re bringing you the screens, the GUI, the UI that you can customise,” he adds. “We’re doing the back-end and the front-end for you in one piece.”

So far, Scringo, which raised a $700,000 seed back in March from Israeli VC Inimiti and “several other angel investors” — and is apparently in the process closing a Series A — is seeing the greatest traction for its platform among developers in the U.S., U.K. and Germany, and in the games app category. It’s keen to expand on this.

“We’re trying to expand both on vertical and on industries. Now we’re very into games. We’ve opened up our platform for Unity, for game developers to operate it on Unity. So we’re very strong now in games and trying to also fight other verticals in terms of demography,” says Avrahamy.

“There’s a million people that are using your app — using your property. And we just want to help developers understand that — let your users talk to each other, let them communicate. You have created that one thing in common for them. You have that common interest. Let them express themselves.”