Electricity in Jakarta, Indonesia costs three cents per kilowatt hour. That’s 30 cents less than power in the US and Europe. This means, all things being equal and provided you don’t mind your apartment heating up alarmingly, you can make a decent living mining for Bitcoin and Litecoin (another cryptocurrency) using powerful – and hot – graphics cards, each one running at 140 degrees Fahrenheit or more.

That’s exactly what Tiyo Triyanto has decided to do. Using some off-the-shelf components he has jury-rigged a 105 GPU system that can, with intense maintenance, make him $114 a day.

The system, a chain of motherboards, cards, and ethernet cable so convoluted that you could imagine it powering a mad scientist’s lab. Instead, Triyanto has created a very precise and complex mining platform using his own – secret – configurations.

“Currently I’m making about 60 litecoin per day,” he said. “I’ve kept 95% of the mining profit since April and once the major exchanges start accepting LTC, others will follow, and price is expected to soar. So that 60 LTC could turn into $1,500.”

Jakarta, where the temperature hovers around 80 degrees and climb to a balmy 95 with 75% humidity is obviously not an ideal environment for a set of machines that require constant cooling. To keep things from burning up Triyanto aims his machines in different configurations and maintains air conditioners that run in his home all night and day.

“However, having cheap electricity is not enough for me,” he said. “I kept optimizing my mining farms, did a lot of research and testing, built an effective air cooling method, and created heat flow management and hardware airflow alignment, all in the effort to maximize the mining uptime. When I started I was too eager to get it working and missed a lot of testing.”

In one way Triyanto’s system is genius. Like Kramer in Seinfeld who attempted to cash in on the pricing disparity between bottle returns in New York and Michigan, CS grad Triyanto is cashing in on his home country’s relatively low electricity costs. This arbitrage, while ingenious, could end as sadly as Kramer’s own adventure. Triyanto’s amazing system will be outpaced soon by faster, more efficient mining rigs. In short, this complex, expensive, and seemingly profitable mining rig is about to be eclipsed by newer and better technologies at a pace far faster than the average user can match.

Welcome to the Bitcoin arms race. Things are just getting warmed up.

Bitcoin mining is like making money out of thin air. Bitcoin is a controlled currency supply and, as Wikipedia notes, “it requires exertion and it slowly makes new currency available at a rate that resembles the rate at which commodities like gold are mined from the ground.”

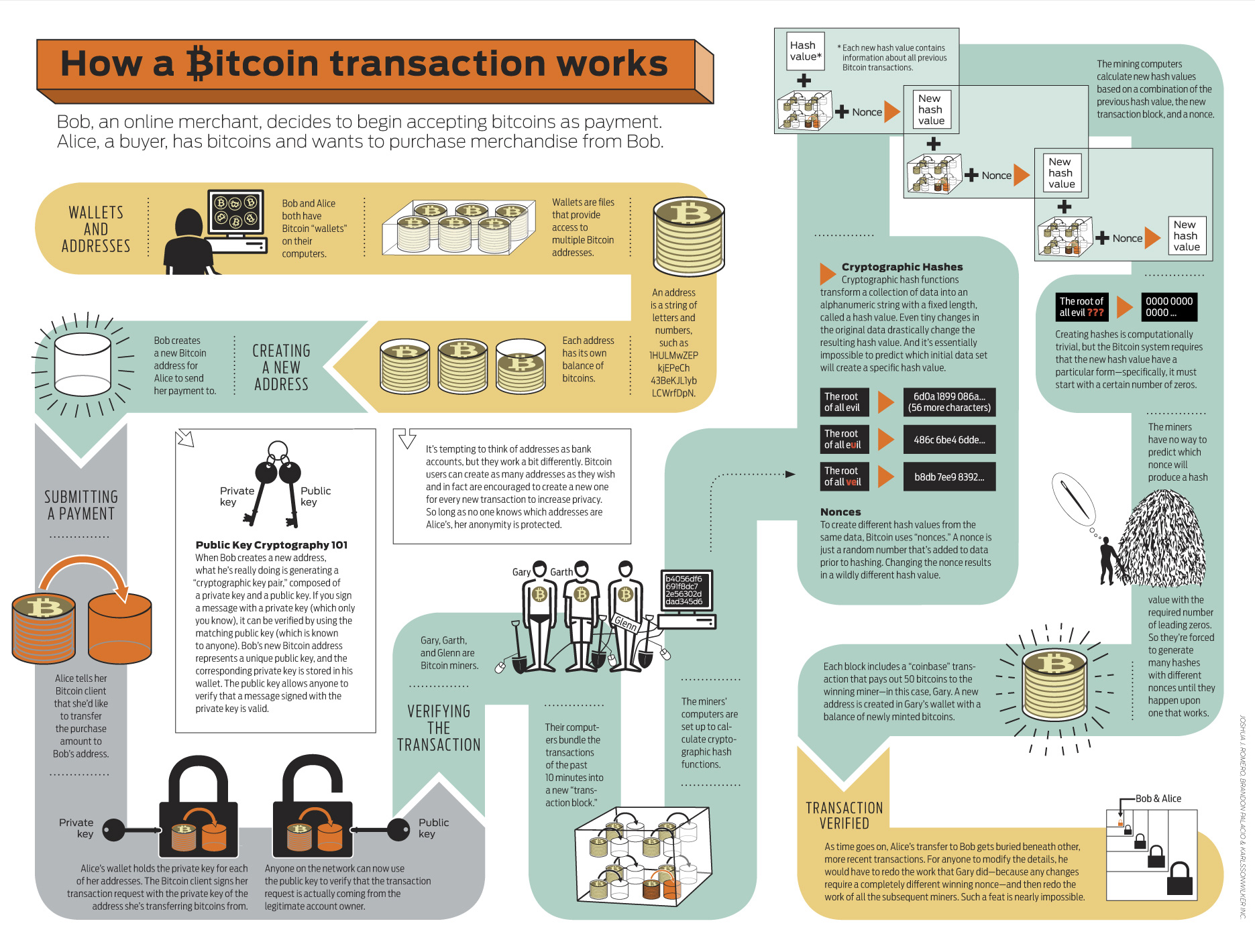

Bitcoin is a mix of three monetary processes. First, it handles its own transaction processing (think credit card companies,) fraud prevention (the SEC and security firms), and currency issuance (the treasury.) In a real world these things are very complex systems with many moving parts. The beauty of Bitcoin is that each of these systems are reduced to very simple, very powerful cryptographic methods that ensures that each step in the chain verifies the next.

Adam B. Levine, Editor-in-chief of Bitcoin podcast Let’s Talk Bitcoin describes it in another way:

“Mining is like a race occurs every ten minutes where participants from around the world all compete to solve a math puzzle, when someone finds a solution, all the transactions since the last puzzle was solved are wrapped up into what’s called a block.”

These blocks are sent out every ten minutes as a package of cryptographically verified transactions – the buys and sells of the system. Your computer, while it’s mining, is actually verifying and encoding these transactions and, as a reward,if you encode the block you get 25 Bitcoins. Computationally it’s akin to getting a few hundred dollars for rolling a massive boulder up a mountain. And then the boulder rolls down again. Groups can get together and mine concurrently, sharing in the proceeds, but the resulting payouts are minuscule – perhaps a few dollars per day at the very most.

Mining speeds are measured in number of hashes processed per second – megahashes (MH/s) and gigahashes (GH/s) are the common notation. A hash is a way to “compress” a long number into something that can be used by a computer to, say, find a piece of data in a database. Some have called the hash a long number’s resume.

The goal of processing is to find a hash that has a sufficient numbers of zeroes at the beginning. This signals the completion of the block and pays out the reward from the coinbase – an imaginary mine containing all possible Bitcoins.

Bitcoin appeared on January 3, 2009 and slowly ramped up in popularity over the next few years. Originally created by the mysterious researcher (or researchers) going by the alias Satoshi Nakamoto, the system was designed to give early adopters an improved chance of mining Bitcoins. When Satoshi began, the fastest way to mine Bitcoins without burning up your computer was by forcing the computer’s graphics processor to run the process in the background. Because these GPU units were inexpensive and good at handling complex equations, you could squeeze a few hundred megahashes per second out of them resulting in a few Bitcoins a week. They peaked at about 600 MH/s but, depending on the hardware and the setup, they could reach gigahash levels.

For a while miners were tooling along, pumping out Bitcoins and sharing tips and tricks for maximizing their setups. Bitcoin mining was a hobby.

Now it’s not.

In April 2011 Satoshi was gone. He (or they, or her) told a Bitcoin developer that he had “moved on to other things,” a decision that had little impact on Bitcoin. Two years after pressing the start button, Bitcoin was steaming along under its own power. Exchanges rose and fell – the most famous one being Mt. Gox in Tokyo, Japan. Mt. Gox was originally a Magic: The Gathering Online Exchange (M.T.G.O.X.) but switched to Bitcoin transactions in 2011. Tibbane Ltd. bought the company in March, 2011 and it has survived countless attacks, hacking attempts, and serious losses. Today Mt. Gox deals in about a million Bitcoin a month.

GPU mining worked well for a while but, thanks to the natural inclination of the miner to add more and more power, the average gain from a few more megahashes fell exponentially.

“Its like if your computer got slower every time someone new bought a computer, or someone upgraded to a faster one,” said Levine. As single GPU mining fell to parallel mining the speeds seemed to explode – along with energy usage. Rigs that could mine a few Bitcoins a month were now mining a few Satoshis – the miniscule parts of the Bitcoin after the decimal point and the electricity need by GPUs was frighteningly wasteful. In the end you spent more on the hardware and energy than you could ever sanely mine.

And so the arms race began.

First users tried field-programmable gate array machines – chips that could be specially programmed after manufacture to do nearly anything. These boards hit about 400 MH/s at 15W, considerably less than GPUs and at similar rates. By 2012 a few manufacturers were offering dedicated FPGA devices that could hit GPU speeds. Then, in 2012, FPGAs were outpaced.

First users tried field-programmable gate array machines – chips that could be specially programmed after manufacture to do nearly anything. These boards hit about 400 MH/s at 15W, considerably less than GPUs and at similar rates. By 2012 a few manufacturers were offering dedicated FPGA devices that could hit GPU speeds. Then, in 2012, FPGAs were outpaced.

Bitcoin rose in notoriety thanks to the rise of Silk Road and the Cyprus economic crash. June 2012 brought Y Combinator-backed Coinbase and the Winklevoss twins of Facebook infamy invested $11 million in the currency while calling it “better than gold.”

In April 2013 it reached an all-time high of $266 per Bitcoin, a stratospheric rise. Accounts that once were worth a few dollars exploded and early users cashed out. A number of folks I talked to described selling their Bitcoin and buying gold bars, cars, and fancy watches. They were either further compressing their wealth into relatively non-volatile investments or just having fun.

It was an arms race. “It’s now about getting the newest technology first and deploying before anyone else can,” said Levine. After FPGAs users discovered single-purpose, low-power ASIC chips, the entry-level models being the USB-powered ASIC Sapphire Block Erupters. These tiny ASICs could be installed in parallel on a standard USB hub and run at a few gigahashes – provided you kept things cool. A small mining rig I have set up under my desk uses two Block Erupters and maxes out at 600 MH/s a second – enough power to mine a dollar every six days.

On October 15 the first KNC Jupiter mining rigs hit the network. These $5,000 machines can mine at 500 GH/s at about 500 Watts, a power to mining trade-off that many would be willing to make. A back-of-the-envelope calculation let you expect to see profit of $6,000 from these machines every six months – impressive at first but with each new KNC rig brought online the difficulty is increased.

Heavier iron pops up on the forums and Bitcoin fan sites with alarming regularity. One company, Cointerra, is promising 1 TH/s – that’s 1000 GH/s – for $6,000. Other manufacturers opened up shop offering massive speeds and close up almost immediately – taking preoders with them. One company, Terrahash closed up suddenly in September 2013, writing: “We will be able to refund about 50% of every order with this amount. We are trying to get our money out of Chase, which will help us refund another ~5% of each order. We are trying to return as many components as we can, and as soon as we get more money back, we will send additional pro-rated payments to each order.”

The buyers were understandably incensed, writing “Don’t think you can scam people to accept a 50% deal for YOUR failures. Customers are not responsible for the risks you took.”

In short, Bitcoin mining has become a fool’s game. The instant a new batch of mining tools hits the streets the total processing power of the Bitcoin hive mind rises. When KNC released its product the total power of the network went from 1 petahash per second to 2 petahashes per second. Many expect the network to hit 3 petahashes in the next month. As a measure of pure computing power the Bitcoin mining system – the actual number of machines blasting away at each block – has exploded… over and over again.

“ASICs have increased difficulty and are making mining increasingly out of reach for anyone but very deep-pocket miners,” wrote Reddit user Subduction. “It is concentrating more and more mining power into fewer and fewer hands, leaving the network at substantial risk for a 51 percent failure.”

Click to enlarge

[Image via Spectrum.IEEE.org]

For their part, manufacturers like Cointerra are trying to support the small miner.

“We are actually selling to the retail guys, the low-end miners,” said Ravi Iyengar. “We don’t want to focus on enterprise mining because we want it to be distributed. And that’s the whole idea behind Bitcoin: keep it distributed, decentralized, not put all the hash in the hands of the field, and we want to increase that and build that.”

But Bitcoin is now a big business. With Valley investment and worldwide interest – especially as a medium of exchange – many users are moving towards hosted solutions. Leasebit (warning: auto-playing video), for example, offers a lease-to-own model for 1.49 TH/s machines that cost $149 a month. You own the machines outright in 59 months. Rowan Alter, VP of sales at Leasebit, sees the hosted model as the only way to fly.

“If somebody wants to own a miner that actually works it will be so sophisticated, so hot, and so loud that you will have to outsource to a firm of your choice to maintain it,” he said. “I think the day of the little guy plugging in a chipset is over.”

Where can mining go next? All indications point to large farms where users lease out powerful machines or, barring that, the entrance of large, well-heeled banks that simply continue the ASIC race at a much higher scale. As the difficulty increases the resulting firepower needed to squeeze out a single Bitcoin will raise exponentially.

After years of easy returns and rising prices, Bitcoin mining has hit a point where it is all but futile to try to mine at home. Funds like Coinlab are busy building Bitcoin data centers like Alydian where massive banks of ASICs run 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Not unlike the early Internet, Bitcoin is growing slowly and then all at once. In a way, it’s just what Satoshi would have wanted.

About as far as you can get from Jakarta, another miner was blasting away at the block chain. Julian Rodriguez, 26, lives in the Bronx and, in February, 2013 purchased an $1,500 Avalon ASIC miner that could do 82GH/s . He overclocked it – forced it to run faster than its original specifications – and succeeded in mining $16,218 since June 21st.

“I had just started my own consulting business and money was tight, I put a lot on the line for that machine. After overclocking it, the fans ran on full blast at all times, and there was a constant hum in my room. My girlfriend didn’t mind too much,” he said. He ran an air conditioner all summer to keep his room cool at a cost of about $60 a month.

He recently sold his Avalon on eBay for $1,725. It’s a profit of about $16,500, less expenses. He pulled hundreds of dollars out of the machine the way Jack’s giant pulled golden eggs from his magical goose. The box, a nondescript metal enclosure with three massive fans containing some of the fastest, single-purpose computing circuitry available to consumers, is a strange thing. To some it’s the future of currency, a way to free us from the chains of fiat tyranny. To others it’s a hobby with little upside. To still others it’s an investment as sure as gold or municipal bonds. It’s Schrödinger’s currency generator, containing nothing and everything at once

Why did Rodriquez sell his miner? He’s done mining and sees trading as the next big thing.

“I personally feel like it’s now time to trade Bitcoin itself. Buy coins in cash and trade,” he said. He estimated that he’d make about $800 more before January and then watch the machine burn itself out, his processing power winking out like a hot, strange star. But he was amazed at the power the Avalon afforded him.

“I’m a Bitcoin believer. I’m just waiting for the rest of the world to get it,” he said.

Illustration: Bryce Durbin; Infographic: Joshua J. Romero, Brandon Palacio & Karlssonwilker Inc.