Music production can be a nightmare. If you don’t save after every change, you can’t go back, and it’s tough for collaborators to know who tweaked what. Splice wants to redefine the musician workflow. The new startup from GroupMe co-founder Steve Martocci opens its private beta today that lets artists auto-backup every update to a song, and share a timeline of changes and comments with their team.

Splice fittingly started as a conversation at a concert. Martocci was talking to his friend Jon Gutwillig, the guitarist from jam band The Disco Biscuits who’d just picked up programming. He said to Steve, “You have these awesome tools for creating software. Where are those for the music industry?” Martocci got to thinking, but was tied down running GroupMe, which would eventually sell to Skype (later bought by Microsoft) for a sum rumored to be over $40 million.

Later, Martocci met Splice co-founder Matt Aimonetti, formerly of LivingSocial and Sony PlayStation, at a conference in Columbia. The two realized they wanted to work together, and when Steve found out Matt had spent half his life as an audio engineer, they decided to dive into the music space.

What they found was that when it came to the system artists used to save and share their works-in-progress, “In the majority of cases, people are doing nothing” Martocci tells me. So they decided to build Splice with the goal of leaving the core music creation process the same, but eliminating all the annoying stuff around it.

What they found was that when it came to the system artists used to save and share their works-in-progress, “In the majority of cases, people are doing nothing” Martocci tells me. So they decided to build Splice with the goal of leaving the core music creation process the same, but eliminating all the annoying stuff around it.

The product won’t be publicly available for a few months, but today Splice is revealing the idea and starting to take sign-ups from musicians for the private beta. The startup is running with $2.75 million in seed funding led by Union Square Ventures, and joined by True Ventures, Lerer Ventures, SV Angel, First Round Capital, Code Advisors, Warner Music Group COO Rob Wiesenthal, TechStars’ David Tisch, and Turntable.fm’s Seth Goldstein.

Writing Songs Like Software

From the start of creating a song to offering it up to the world, here’s how Splice works. Artists download the Splice client. For now it only works with popular music production software Ableton, but support for Logic, Pro Tools, Reason, and more is planned. Splice creates a directory on the musician’s computer. Whenever they save a track they’re working on to it, it’s automatically saved to the cloud along with any dependent sample files.

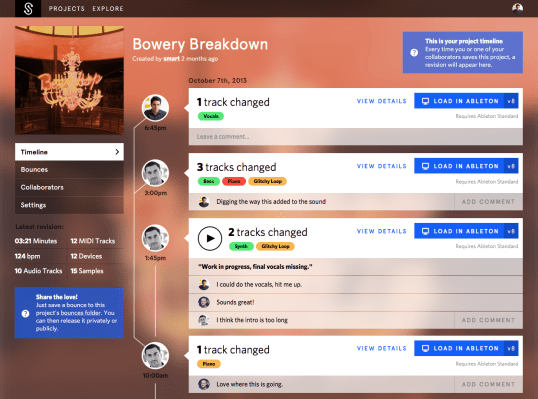

This save along with details of what tracks are in the file are added to the user’s Splice timeline. They can revert back to any of their saves, essentially going back in time. To share a project with collaborators, there’s no need to send seas of Dropbox files, MegaUpload-style links, or physical hard drives anywhere. The project creator just adds their co-conspirator’s email address to Splice and they get access to all the saves and Timeline.

Whenever any collaborator makes changes to the project, an update to the timeline shows what tracks, like guitar or vocals, they altered. Everyone can add comments to discuss changes too, so there’s less need to run parallel email or chat conversations.

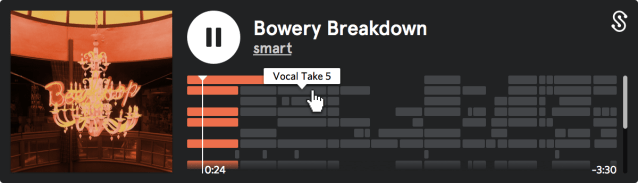

When the song is ready for its debut, Splice users can click a single button to convert it into a standard music file like an MP3 and make it publicly listenable in what Splice calls the DNA Player. This music player lets fans leave comments somewhat like SoundCloud, and also visualizes the song not just based on its wave form but on the underlying tracks. Finally, the artist can even make their track publicly remixable to collaborate with the whole world.

“When I think of our biggest competition, it’s people not doing anything”, Martocci tells me. Update: Well, nothing, and Blend.io, a Betaworks company that launched earlier this year. It focuses more on giving producers a public profile to show off their work, but also aids with collaboration like Splice.

Still, the question is whether Splice can make its product strong but simple enough to get historically stubborn musicians to change their habits. Splice could feel too centralized or constricting compared to the DIY creation and collaboration that music makers are used to. But if Splice can make a product that artists love, Martocci says that luckily “the most powerful growth strategy is word of mouth, and musicians talk to each other.”

As for a business plan, Martocci says “We’ll have a premium model. Our goal is not to make money off storage.” But what Martocci is more excited about than just a paid version of Splice with extra features is the potential to align incentives with artists and make money by helping them make money through distribution.

Imagine if an artist’s biggest fans could pay $100 to hear early demos of songs from a new album and provide feedback on them. “There’s this gap between Spotify and Kickstarter. What about inviting fans into the studio, extending music creation to the listeners — expose the process to fans and let them get involved. That’s our end game” Martocci told me with a dream in his voice. We’ll see if musicians get hooked.