Often it’s not what you say, it’s how you say it that matters. Especially if you’re being sarcastic to a customer services operator. Such nuance is obviously lost on automated speech systems, more’s the pity (and, indeed, on some human ears) but don’t give up hope of being able to mock your future robot butler with a sassy response. UK startup EI Technologies, one of 17 in the current Wayra London incubator cohort, is developing a voice recognition platform that can identify emotion by analysing vocal qualities with an accuracy rate it says is already better than the average human ear.

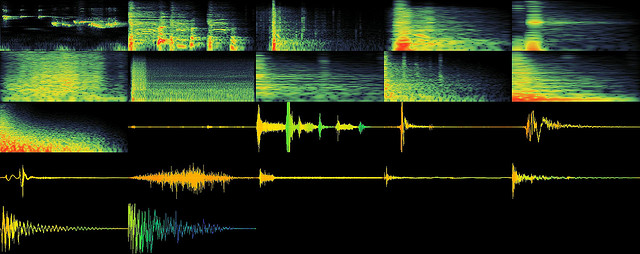

EI Technologies’ algorithm analyses the tonal expression of the human voice, specifically looking at “acoustic features”, rather than verbal content — with the initial aim of powering a smartphone app that can help people track and monitor their moods. The idea for the app – which will be called Xpression, and will be launched in a closed-alpha by the end of the year, specifically for members of Quantified Self – is to help “quantified selfers” figure out how their lifestyle affects their well-being. But its primary function is to be a test-bed to kick the tyres of the technology, and allow EI to figure out the most viable business scenarios for its emotional intelligence platform, says CEO Matt Dobson.

Ultimately, the startup envisages its software having applications in vertical industries where it could help smooth interactions between humans and machines in service scenarios, such as call centres or the healthcare space. Understanding tone could improve automated response systems by helping them identify when a customer is actually satisfied with the response they have been given (pushing beyond current-gen semantic keyword analysis tech that crudely sifts call transcripts for swear words or other negative signifiers). Or, in a mental healthcare scenario, it could be used to help monitor a dementia patient’s moods. A third possible target market is the defence industry — it’s not hard to see use-cases around tracking soldiers’ stress levels and mental well-being, for instance.

“Initially it’s all about building awareness of capability in your potential customer base,” says Dobson, explaining why it intends to launch a quantified self app first, rather than heading straight into one of these industry verticals. “At the moment people don’t know this sort of technology exists, and therefore how do you understand how it might be used? We’re starting to have those sort of conversations and it’s a matter of trying to bring it to market in a way that you can prove how good this technology is, and also learn how it works well for ourselves — because there’s no benchmark out there that can tell us how good it needs to be to do this.”

Augmenting natural language processing algorithms by adding the ability to recognise and respond appropriately to emotion, as well as verbal content, seems like the natural next step for AI systems. Blade Runner’s Replicants were of course fatally flawed by their lack of empathy. Not that grand dreams of sci-fi glory are at front of mind for EI Technologies at this early stage in their development. As well as core tech work continuing to improve their algorithm, their focus is necessarily on identifying practical, near-term business opportunities that could benefit from an empathy/emotional intelligence system. Which in turn means limiting the range of emotions their system can pick up, and keeping the deployment scenarios relatively specialist. So an empathetic Roy Batty remains a very distant — albeit tantalising — prospect.

Currently, says Dobson, their algorithm is limited to identifying five basic emotions: happy, sad, neutral, fear and anger – with an accuracy rate of between 70% to 80% versus an average human achieving around 60% accuracy. Trained psychologists can apparently identify the correct emotion around 70% of the time — meaning EI’s algorithm is already pushing past some shrinks. The goal is to continue improving the algorithm — to ultimately achieve 80% to 90% accuracy, he adds.

The system works by looking for “key acoustic features” and then cross-referencing them with a classification system to match the speech to one of the five core emotions. EI’s special sauce is machine learning and “a lot of maths”, says Dobson. They also enlisted U.K. speech recognition expert Professor Stephen Cox, of the University of East Anglia, as a paid adviser to help fine-tune the algorithm. Dobson notes that Cox has previously worked with Apple and Nuance on their speech recognition systems.

Developing the algorithm further so that it can become more nuanced – in terms of being able to pick up on a broader and more complex spectrum of emotions than just the core five, such as say boredom or disgust — would certainly be a lot more challenging, says Dobson, noting that the differences between vocal signifiers can be subtle. In any case, from a business point of view it makes sense to concentrate on “the big five” initially.

“It’s better to be more accurate or at least as accurate as a trained human, rather than trying to expand your basic emotions initially,” he says. “You’ve got to look at the value and think – there’ a value when a process can tell someone’s getting angry with it. Whereas where’s the value in knowing the difference between boredom and sadness or loneliness? It becomes a bit less obvious when you start to look at it.”

(Philosophers and sci-fi fans may disagree of course.)

EI Technologies is not the only startup in this area. Dobson cites Israeli startup Beyond Verbal as one of a handful of competitors – but notes they are targeting a slightly different result, seeking to identify how someone wants to be perceived, rather than focusing on their immediate “emotional layer”. He also mentions MIT spin-out Cogito as another company working in the emotional intelligence space.

One way EI Technologies is differentiating from rivals is by its intention to have its system work on the client device, rather than using cloud processing which requires connectivity to function. That will then free it up to be deployed in a variety of devices – not just smartphones but other devices such as cars where cellular connectivity isn’t always a given, says Dobdon.

The startup, which is in the middle of its stint at Wayra London, is backed by around £150,000 ($230,000) in seed funding – which includes Wayra’s investment and also finance from the UK government’s Technology Strategy Board. Dobson says it’s planning to raise another round of investment in February next year, unless a VC comes calling sooner.”If we had top up finance just now we could accelerate our programme,” he adds.

[Image by Iwan Gabovitch via Flickr]