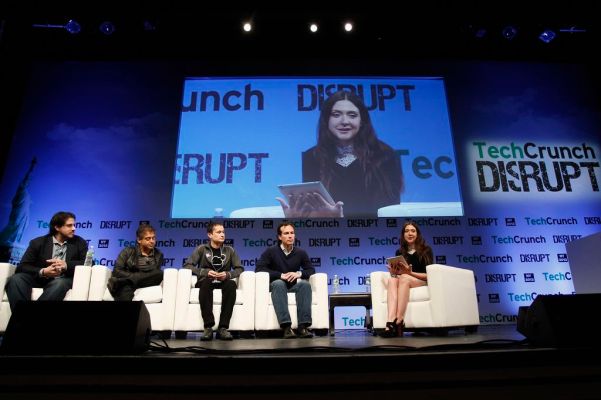

When should an entrepreneur raise money, who should they raise from….and, well, should they even raise? These were some of the questions discussed on a morning panel at TechCrunch Disrupt NY 2013, which included participation from Mike Abbott of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, Aaref Hilaly of Sequoia Capital, AngelList’s Naval Ravikant, and Box Group’s David Tisch.

Pitching A Partner Vs. A Firm

The VCs debated the various merits of pitching or working with an individual partner at a firm, versus considering what the entire firm could offer, in terms of guidance and experience. Abbott said that at KPCB, each partner has a different set of experiences to offer. Hilaly challenged that, while that’s true, the premise that it’s a single VC partner is most important to a founder, noting that individual partners are not as important as the collective partnership, like at Sequoia. There, everyone has their own specialities, but the entire firm gets behind the company, he says. (And yes, even Color, he admitted, responding to a question from the panel’s moderator, TechCrunch co-editor Alexia Tsotsis.)

Ravikant, however, offered a different, more challenging answer to the question about who and how entrepreneurs should determine who to work with and pitch to: just use AngelList. “As a technology entrepreneur, I wanted to solve the problem with a product,” he explains, adding that he tells founders to use the product, and “call me later if you fail.”

The A Round

When an entrepreneur has moved beyond the seed stage, the next question that typically gets asked is who to raise the A round from? Tisch says that’s an impossible question to answer. The only data point you have is that someone has invested in another company like yours before, or has recently blogged about their interest in similar technology, he explains. When someone asks him about the A round, he replies, “just go meet with them all and see who’s interested.” The problem, he continues, is that VCs can’t really advertise their interests, because it would be limiting.

That being said, he admitted that being New York-based himself, he likes to send founders to area firm USV.

What Do You Want To Fund?

Then, the burning question that entrepreneurs are continually curious about: What areas do you want to invest in? Abbott responds with a fairly pat answer that KPCB is about investing in the technology that can enable the world-changing trends. Tsotsis wanted to know if Google Glass now fits that description, but he said he’s thinking more about sensors on the body, data and machine learning. Hilaly also seemed a little skeptical about Glass as a consumer device, saying that, though he loved that Google took these so-called “moonshots,” he foresees more commercial applications for Glass than the consumer apps people are excited about today.

Ravikant added that the best way to invest – like he does – is to look at companies that are an extension of your life to date, meaning those you have a personal connection and belief in. Tisch seemed to agree, talking about how he likes things that use the Internet to make his life easier.

Easier? asked Tsotsis.

“I can’t press a button had have food come out of the wall yet,” he joked, before offering deeper insight – that technology in the car and home will become more passive in the future, without users having to take some action first.

Entrepreneurs Have More Choice – But That Doesn’t Mean They Should Raise From VCs

The investors then discussed the biggest threat – or rather, disruption – to their own industry in recent months, and the agreement was that it has become significantly easier to raise early money. Entrepreneurs today even have far more choice in terms of who they choose to take investment from than these VCs did back when they were raising as founders themselves. But while it has gotten easier, there’s a flip side – cautions Hilaly, “don’t start a company because you can.”

The diffusion of talent because of this improved ability to raise may prevent talented folks from working at larger firms like Facebook or Google, where they may actually have a bigger impact, and which are a better use of skills.

Tisch, instead of dismissing these smaller-scale companies, says the larger trend at play here is the rise of a new class of technology businesses. He referred to these as lifestyle businesses, those with maybe a $10 million to $15 million upside, but aren’t venture-scale. There’s not an investor class to fund these companies yet, he says, but thinks crowdfunding will help these kinds of companies scale.

There’s nothing wrong with smaller businesses with smaller exits, but it becomes a problem when these kinds of startups try to force themselves to have a larger vision just to go after the VC money they need to scale.