While the number of seed financing deals has ballooned over the last few years as the cost of starting a company has fallen, the pace of Series A venture deals hasn’t kept up.

Now it looks like the bottleneck between the seed stage and the Series A level has gotten even tighter, according to a survey from Fenwick & West, one of the best-known law firms for startups in Silicon Valley. In their annual survey of companies they work with, they tracked 61 transactions from last year, 56 the year before and 52 in 2010.

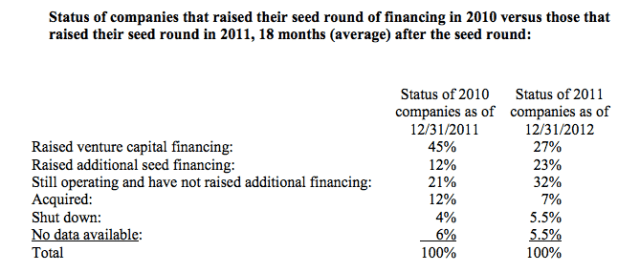

What they found was that even fewer companies had raised Series A rounds by the end of the year after their seed deals closed. Only 27 percent of companies that raised in 2011 were able to pull a Series A round by the end of 2012. In contrast, 45 percent of companies funded in 2010 were able to secure a Series A round by the end of 2011.

What’s interesting is that follow-on financings are picking up some of the slack here. More companies are relying on follow-on seed financings if they can’t get to a full A round. Twenty-three percent of companies funded in 2011 did follow-on seed rounds, compared to 12 percent of companies in 2010. Basically, the path from seed to proving you’re worth a Series A round is just getting longer.

What’s interesting is that follow-on financings are picking up some of the slack here. More companies are relying on follow-on seed financings if they can’t get to a full A round. Twenty-three percent of companies funded in 2011 did follow-on seed rounds, compared to 12 percent of companies in 2010. Basically, the path from seed to proving you’re worth a Series A round is just getting longer.

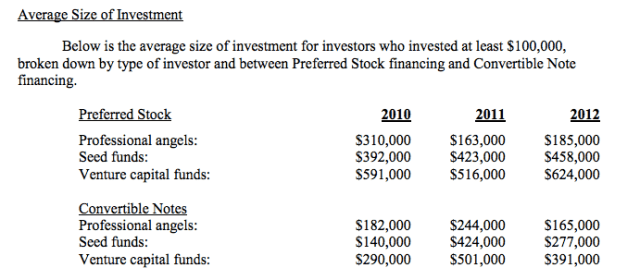

At the same time, traditional VC firms are getting more active at the seed level, and led about 34 percent of seed deals in 2012, compared to 27 percent in 2011. You can see that the average size of investment for VC funds in these seed deals rose slightly, while the average investment size from professional angels declined.

Not only that, the deals themselves are starting to look more conventional. The use of preferred stock structures rose to 67 percent last year, from 59 percent in 2011.

“It says two things. The leverage is changing a bit,” said Barry Kramer, a Fenwick partner in the corporate group. “Last year, the entrepreneur had a bit more leverage than they have right now to get the terms they want. But it’s also a reflection of how more sophisticated investors like venture capital groups are getting involved with seed financing and they’re saying — ‘This is how we do it.'”

That said, it’s not all black and white. He pointed out that the average pre-money valuation on those more traditional preferred stock deals rose to $4.6 million last year, from $3.8 million the year before.

Meanwhile, the average valuation cap on convertible note financings (which have been used in the past as a bridge to a priced Series A round) fell $6 million last year from $7.5 million in 2011. Convertible notes became a popular choice, in part, because they postpone pricing a company until a Series A round when a startup presumably has more traction and the numbers to prove their worth.

So is this good? Is this bad? What?

The “Series A Crunch” often feels like it’s written about in apocalyptic terms.

But the thing is, if the cost of creating companies has fallen, we should be trying a greater number of experiments. If a proportional amount of them are simply not that good or don’t get traction to graduate onto the next level, that’s okay.

The other criticism of the easy seed financing environment is that it splits talent between too many companies. People who otherwise would be great mid-level hires or leaders at growth-stage companies are eschewing those jobs for starting their own companies. It is a legitimate concern. Great companies like PayPal and Google emerged in part because they had a serious concentration of talent relative to other companies in the Valley.

Yet it’s hard to argue that a world in which more people get a chance to build something themselves and take ownership of it is a bad thing. Even if they fail, they filter back into the system either as more seasoned entrepreneurs on their second or third startups or as leaders in big companies who are more fearless about making change.

“Truthfully, there should be a Series A financing crunch,” Kramer said. “You put a small amount of money into a large amount of companies and some of them won’t work out. It’s not horrible. It’s part of a healthy ecosystem in general.”