As I watched the Google antitrust hearings last Wednesday, with its gotcha moments and Senators pontificating about the dangers Google poses to society, it struck me that what I was watching was theater. And not just any theater, but monopoly theater. I am borrowing from the concept of security theater: “a term that describes security countermeasures intended to provide the feeling of improved security while doing little or nothing to actually improve security.” In the same way, talking about Google’s monopoly power and what the government should do about it provides the feeling of improving competition while doing little or nothing to actually improve it.

The hearing touched upon many serious concerns about Google’s market power, but in the end it was just monopoly theater. Nothing antitrust regulators do to Google will actually improve competition.

With 65 percent to 70 percent search market share in the U.S., 75 percent share of search advertising, and 95 percent share of mobile search (according to numbers thrown out during the hearing), it is not too difficult to make the case that Google does wield monopoly power in search. However, being a monopoly in and of itself is not illegal. The government would have to prove that Google is abusing that monopoly power in an anticompetitive way in order to take action, and that is where things get tricky.

Google in many ways is a natural monopoly. It benefits from its own unique economies of scale. The more people who do searches, the more data it gathers to pour back into its algorithms to produce even better, more accurate results. The more people who use Google, the more valuable it becomes to the search advertisers trying to reach them. So there are subtle network effects on both the consumer search and advertising sides of the equation.

Since Google offers most of its products to consumers for free, it is difficult to argue that consumers are being harmed, as Mathew Ingram pointed out in a post on GigaOm. But direct consumer harm is not the only test for anticompetitive behavior. Taking actions which drive competitors out of the market can be considered anticompetitive because it reduces consumer choice.

The main question the Senate hearing was trying to address was whether Google increasingly is using its dominance in search to favor its own products over those of competitors. Does Google Places hurt Yelp, or does Google Product Search hurt NextTag? It certainly does. In Yelp’s case, Google used snippets from Yelp reviews to help build Google Places (more recently, it bought Zagat). Yelp protested, but was told if they didn’t like it, they could block Yelp results from showing up anywhere on Google, including in natural results. This was a false choice because 75 percent of Yelp’s traffic comes from Google in one way or another. “Not being in Google is equivalent to not existing on the Internet,” Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman testified during the hearing.

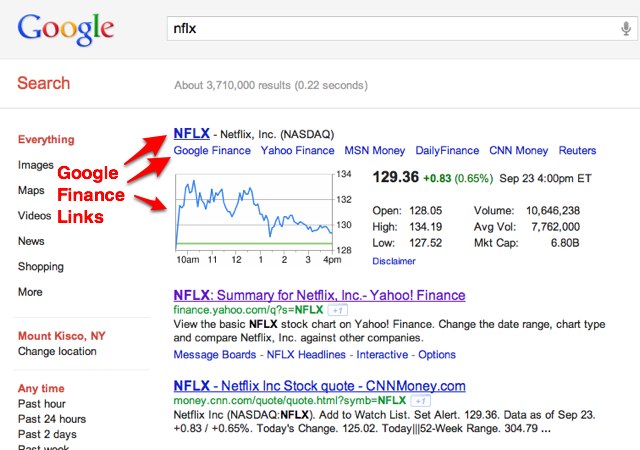

Another example that kept coming up during the hearing was Google Finance results which appear summarized at the top of Google when you search for a stock symbol, much in the same way that Google Places results take up a lot of real estate when you do a search for a local business. Google has been presenting these Universal Search results since 2007. If it can give searchers the answer they are looking for right in the results, like a small stock chart, it will.

Responding to a Senator’s question, Google chairman Eric Schmidt said, “In this case we don’t list anyone first. We show a summary, then the results. I disagree with the characterization that we were somehow discriminating against the others.” He pointed out that the first natural result underneath for a stock quote is usually Yahoo Finance, and that Google provides links to competing finance sites in the universal result itself. While this is all true, the first three links in the universal result for a stock quote generally go directly to Google Finance. If you click on the ticker symbol or the chart itself, those go to the Google Finance page, and Google Finance is listed first before Yahoo Finance, MSN Money, Daily Finance, CNN Money, or Reuters just underneath the ticker (see image below).

All of this seems like pretty damning stuff, right? With examples like these, it is possible to show that Google does use its dominant position in search to drive consumers to its other products. Shouldn’t Google Finance, Google Places, and all of Google’s other non-search products succeed or fail on their own merits? It is a common practice for companies to introduce new products to its existing customers, but again, different rules apply to monopolies. And Google might be wise to curtail some of these practices on its own before the government does it for them.

But even if Google is hurting specific competitors, that does not mean it is hurting the market as a whole. After all, Google changes its algorithm all the time, with some sites rising and other sites falling in natural results. Trying to prove whether Yelp or Google Places provides the better results is very subjective. As long as Google can honestly argue it is trying to provide the best results to consumers, it will be difficult for an antitrust court or the government to punish them for that.

Even if Google is abusing its monopoly powers, then what? Any remedies imposed on Google could be worse for consumers than the uncertain consequences of keeping Google unchecked. If Google had to pass every change to its search engine through an antitrust filter that could really screw up search, something which most of us depend on every single day.

The Senators seemed aware of this possibility, asking repeatedly what Google itself would propose for a remedy if an antitrust court ruled against it. Senator Al Franken suggested the possibility of a voluntary technical committee to provide oversight, to which Google’s outside lawyer Susan Creighton responded (quite correctly): “Google already changes its algorithm 500 times a year. I think a technical committee would be too slow to keep up with changes in the market.”

The hearing was monopoly theater. It was also farcical at times. The Senators kept trying to define Google and search in 2004 terms of ten blue links that take consumers away from Google. But search is very different today. Increasingly, Google is trying to give you the right answer in the results themselves. And you know who else does exactly the same thing? Bing. Telling Google that it needs to go back to the 2004 version of itself while Bing and others can keep experimenting with new ways to deliver information to consumers would just hamper innovation in search.

The government and antitrust lawyers can only look backwards. Technology changes so fast that any remedies they impose would be the wrong ones. Look at what happened to Microsoft. It’s monopoly power was eroded by the Internet and Google and (more recently) mobile computing, all unforeseen forces during its own antitrust trials in the 1990s. The same will be true for Google. Search could be displaced by social as the primary way people discover information on the Internet, or maybe some entirely new technology will take hold that nobody is even talking about yet. Monopolies on the Internet simply aren’t as enduring as they used to be.