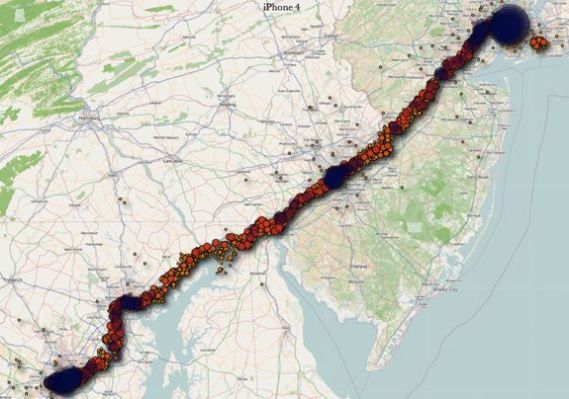

You remember Locationgate, right? It was that massive national scandal that left both Apple and Google at the center of our discontent, after two German researchers discovered that the iPhone tracks and stores location data automatically. The scandal has spurred numerous investigations into where we should draw the line when it comes to location tracking, and one in particular garnered the wisdom of the NSA’s Matthew Olsen, National Counterterrorism Center lead and NSA general counsel.

At a confirmation hearing in the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, Olsen answered the question we had all been asking for a while: can the government use our location data to track us?

The WSJ reports that Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon posed the question, asking if The Man can “use cell site data to track the location of Americans inside the country.” Olsen’s response was ambiguous at best, although he seemed to suggest that the government does in fact have that authority: “There are certain circumstances where that authority may exist,” said Olsen. “It is a very complicated question.”

Well that just about clears it up then, doesn’t it? Remember the good old days when the feds actually had to do a little work to find suspected criminals? Good times. Anyways, since Olsen’s answer fell short of any sense of clarity, the “intelligence community” — another awesomely vague reference — intends to write up a memo that will actually answer the question. A California senator, Dianne Feinstein, asked that the memo be completed by the time the committee reconvenes in September.

The question posed by Senator Ron Wyden inherently steps into the Fourth Amendment’s territory. The Fourth Amendment promises protection and privacy for both the citizen and his or her possessions against unreasonable searches. Whether or not that search is unreasonable is based on the searchee’s subjective and objective beliefs about their own privacy (among other things).

A criminal may subjectively believe that his old cigarette butt is private property but that won’t stop Law & Order detectives from using it to nab DNA evidence. However, if society as a whole collectively believes that the expectation of privacy is reasonable, then evidence collected from the search must be thrown out. In other words, if dirty secrets aren’t kept in a private place, you can say goodbye to your privacy protection.

But are phones private? We lock them up with passwords, and we certainly don’t “borrow” each other’s phones the way we do clothes, books, and DVDs. So how can data from our private phones be used to track us down?

The reason Locationgate was so upsetting to so many people is because it shattered the perception that our phones are locked down little safes that hold and guard all of our secrets. But Apple and Google both maintain that the data collected is encrypted and anonymous if sent back to the company, which again confirms our original thoughts: our phones are private and it is only reasonable to expect privacy when it comes to your phone.

Hopefully, that memo will read the same.