http://twitter.com/#!/Scobleizer/status/89735254641885184

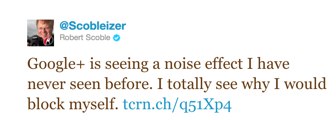

It seems I stirred the pot over the weekend with my post on why I blocked Robert Scoble on Google+. Some of the reaction clearly missed the point I was trying to make. It wasn’t a criticism of Scoble, whose work I like, but a criticism of Google+ algorithms that continually resurface content by those who are popular on the Internet.

I follow Scoble on Twitter and we just became friends on Facebook. Given the way Facebook and Twitter surface content, this hasn’t been a problem at all.

But Google+ continually buries content from my close friends. This is especially important right now when content from real friends is very sparse to begin with because of restrictions on invitations. The Internet famous all have their invites. My real friends are still waiting for theirs. The lack of transparency in the invite process is especially frustrating as I’ve had to do CRM for friends on Google’s behalf. “Did you send me the invite yet?” “Yes, I requested it right away. Google just hasn’t sent it out.”

Algorithms should normalize signals. If a post from Scoble gets only 20 comments, that’s a post that is probably not very important. If a post from one of my close friends gets 20 comments, that’s a Really Big Deal—it’s likely a birth, wedding announcement or job change. Those are the things that I really want to know about.

One of my favorite tech talks is Google’s Peter Norvig talking about the importance of data. He argues that large amounts of data can beat better algorithms. This is important given the current competition in social networks—right now, Google has neither more data nor better algorithms.

Facebook has years worth of data on social interactions among hundreds of millions of people. In market research, it’s commonly known that what people do is very different from what they say they will do. That’s how I feel about Circles. Even if you believe that people will go through the trouble of manually categorizing friends, whether they categorize people in a way that actually reflects their interests is a big open question.

Our explicit decisions often reflect who we aspire to be, not who we actually are. We’d like to think that we want to have dinner with Ban Ki-moon. But we’d rather have dinner with Paris Hilton. Our social networks should be smart enough to know the difference.