You know what’s awful about every politician blindly saying he or she “supports our troops”? It’s usually a hollow sentiment uttered just to get applause.

You know what’s awful about every politician blindly saying he or she “supports our troops”? It’s usually a hollow sentiment uttered just to get applause.

You know what’s great about every politician blindly saying he or she “supports our troops”? When presented with something that demonstrably helps the troops, there’s zero political capital in obstructing it.

And hence, Gunnar Counselman may not only have one of the best entrepreneur names I’ve ever heard, he may also have come up with one of the first Silicon Valley-based, venture-backed online education startups that will help students, make money, and not be crushed by the lame-brain education establishment.

Counselman’s company, Fidelis College, does a few things. At a basic level, it will help active duty soldiers get a headstart on college educations. It enables them to do the first two years of general education requirements online while still on active duty. Later, it helps place them at a major university that’s inline with their civilian career goals. And these students won’t fall into the student loan curse, because there’s military tuition assistance during active duty that will help pay for the first two years of credits and the GI Bill to pay for the last two years of college post-discharge.

But Fidelis aims to do a lot more than that. Like Geoffrey Canada’s model of following inner-city Harlem kids throughout elementary school, high school and college to make sure they don’t fall through the cracks; so too will Fidelis stay with ex-military students, making sure they are taking the right classes, meeting the right mentors and steering towards their dream careers. This starts with a month at “fork & knife school” where the basics of civilian social graces are taught. Beyond that, Fidelis closely tracks the students through graduation and helps with career placement.

Inner-city kids and vets may seem an odd comparison, but they share one thing in common: High drop out rates. Despite triple the education resources in the new GI Bill, less than 6% of military men and women use their complete education benefits and only 25% complete the degrees they start.

Counselman argues a lot of this is social. He likes to quote an unnamed US Marine when he pitches the company: “They spent sixteen weeks turning you into a Marine. They spent the next four years turning you into a bad-ass Marine who will kick down any door in Falluja. They spend an afternoon telling you what it’s going to be like to be a civilian again.”

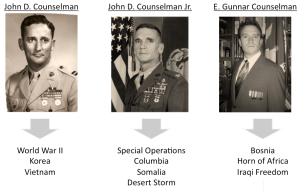

Of course, Counselman knows this all firsthand as a third-generation marine. He served in Operation Iraqi Freedom, his dad served in Colombia, Somalia and Desert Storm, and his grandfather served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. After his discharge, Counselman headed to Harvard Business School.

There’s not a lot to dislike about Fidelis. It helps people who are defending our country. It mostly uses money they are already getting. It makes sure that government money is spent more effectively. And it gives the colleges students who have money to pay their increasingly outrageous tuition. And Counselman says the average score for the military equivalent of the SAT has been increasing since September 11, when enlisting became something that mattered even to many people who had other socio-economic options. It’s now slightly higher than the general US population; it used to be slightly lower.

More than that, colleges get students with a different life experience. Students who have made life or death decisions in combat. Students who have perspective on America’s place in the wider world. Students who understand more than the latest features on Facebook, but what the struggle for survival is all about. Some might call them the anti-millennial.

Counselman’s dad never pressured him to become a marine; in fact he never spoke much about it. But Counselman was struck one day while studying at Cornell, when a kid started to choke in a restaurant and everyone froze. Everyone except an 18-year-old cadet who sprung into action saving the choking student’s life. Counselman wanted some of that, and some of what his father and grandfather had. He wanted to be the guy people turned to in a crisis. “The military is turning out something special,” he says. “It’s just that it’s not a total fit for the civilian world.”

Not only did Counselman get some of that intangible Marine-quality, but as you can see from a slide in his investor deck, the three generations even look remarkably alike:

Many schools already get this: Counselman was surprised to see that 4% of his HBS class was ex-military. After school, he worked as a consultant at Bain where his bosses would plunk down a stack of military resumes in front of him and ask him to parse through them. They knew there was talent to be tapped coming out of the military, but they had no idea what was an impressive achievement and what wasn’t.

A business like Fidelis would be laudable at any point in American history, but it’s especially smart now for a few reasons. There’s an inflection point in our labor markets: There’s an intense talent-war for certain jobs, while millions more can’t find work. Fidelis can help solve the re-training chicken-and-egg problem the country faces for an important subset of people who risked their lives for the rest of us. It’s all the more important post-recession, when 30% of veterans age 22-30 find themselves unemployed.

There’s also an inflection point in the education market. As we’ve written before, for the first time in recent history there’s a debate raging about whether the cost of education is actually worth it. With our preconceived prejudices stripped bare, online alternatives and different approaches to college education are gaining credibility.

And then there’s market demand: The US is winding down operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, reducing the force size from 2.2 million to 1.6 million. It’s in everyone’s interest to give those veterans the best chance to succeed in the civilian world.

And of course, the founder is always key to the success of any startup. Few people understand the scope of this particular problem and have the skills and contacts to raise venture capital and go solve it. I asked Counselman how many venture capitalists had ever served in the military. He knew of exactly four. It’s a massive disconnect from the years just after World War II when nearly every CEO of a Fortune 500 company was a veteran.

Fidelis has raised just raised $2.5 million from Accel and Novak Biddle, a firm that specializes in education startups. Phil Bronner of Novak Biddle Venture Partners noted that Fidelis is in the middle of a new trend of education companies partnering with prestigious, traditional colleges, but building a for-profit business around it.

It’s a reaction to the University of Phoenixes of the world, where much of the revenues are spent getting students in the door, but the graduation rates are low and the prestige of the degree is questionable. And according to a recent report, those colleges have increasingly been targeting the military, without solving a lot of these more fundamental problems veterans face. “A key difference between Fidelis and the others in the for profit industry is the school from day one is going to be focused on outcomes, rather than focused on an ever expanding enrollment,” Bronner says.

For Accel, the deal was a bit outside its norm. Partner Rich Wong said the firm invested because it was one of the first education deals the partnership had seen that was good for students and made clear business sense. “It’s nice to be able to fund a great idea that’s also the right thing to do,” he says.